Published in MYsinchew, Malaysiakini, BusinessToday & Astro Awani, image by BusinessToday.

Although food security received considerable emphasis in Budget 2023, it made no specific mentioning of connecting youth with agriculture.

The Young Agropreneur Programme (Program Agropreneur Muda, or PAM for short), launched in 2014 to supplement the National Agrofood Policy 2011-2020 (NAP1.0) in closing the gap of youth participation in the agro sector, appears to be another programme that could have been worked better towards achieving the desired outcomes and impacts for the nation.

The emphasis on youth participation in agro sector sounded even louder in National Agrofood Policy 2021-2025 (NAP2.0) among its set of objectives, action plans and key indicators. Although the specific mentioning of PAM may not be found in NAP2.0, its emphasis on young entrepreneurs indicate that a similar program will continue to be implemented under the 12th Malaysia Plan (12MP) (2021-2025).

Indirect support exists such as funds that may be allocated to banks such as AgroBank to encourage business venture by youths via financing facilities and other financing schemes for agrifood entrepreneuers, but Budget 2023 should have considered specific allocations so that youth-related initiatives under NAP2.0 could be more directly supported.

While continuation of a programme does not necessarily mean prior success, continuous emphasis does indicate that the need remains relevant—even more so if prior targets were not achieved. Thus, it is important to look back and evaluate the current status so that we can make changes towards achieving the intended targets.

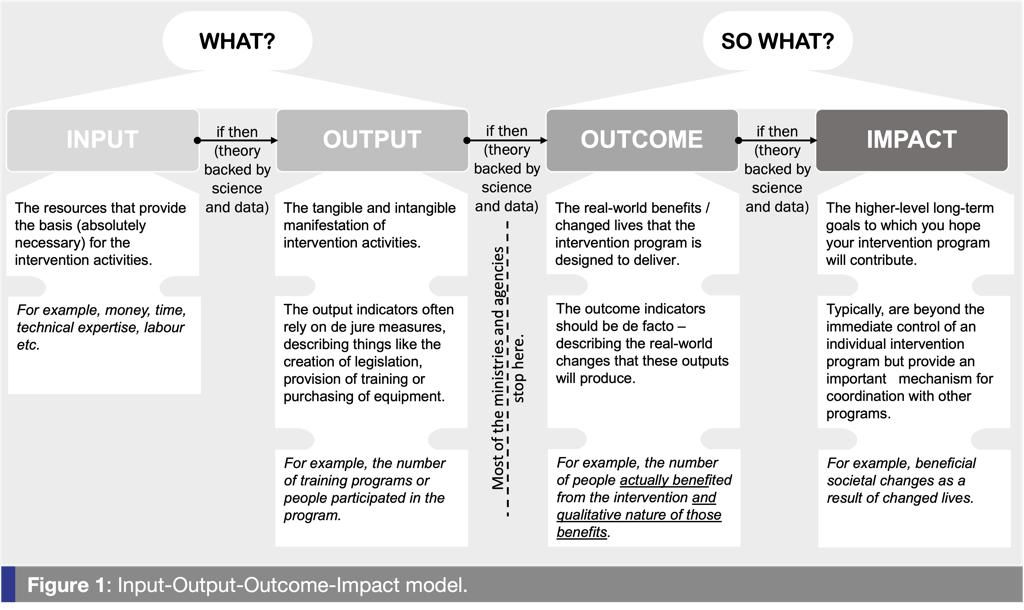

As per what EMIR Research insistently advocates, an impactful programme must be designed by applying Input-Output-Outcome-Impact model (Figure 1). In other words, when policymakers embark on an initiative, they must convince us, the public, that there is a solid basis in the form of empirical evidence and an established body of scientific knowledge to believe that spinning out an N amount of resources on specific outputs will result in the desired outcomes and intergenerational impacts.

Speaking of the PAM, the desired immediate outcome for this programme is the increased share of youth participation in the agro sector and the number of successful entrepreneurs whose income have been significantly improved due to the use of modern technology.

Consecutively, these outcomes are expected to bring greater intergenerational impacts on Malaysians in form of greater Food Security as well as other spillover effects such as more developed and complex industry (as application of modern technologies would naturally boost demand for its local production), reduced food prices and increased disposable income for an average Malaysian consumer (which should stimulate demand for other products and, therefore, overall GDP growth), and reduced overall unemployment and specifically youth unemployment.

However, unfortunately, after almost a decade of PAM, Malaysia faces exactly the opposite—great food insecurity (food security crisis even), shrinking overall industry in terms of its breadth and depth, increasing unemployment and specifically youth unemployment and underemployment, and recent shrinking middle class and increasing B40 (which many economists and policymakers speculate could even be said to be B60 by now).

This is not surprising, because it is also difficult to find in official government documents by the relevant agencies the detailed outcomes and impact of these programmes. Most accounts are on the inputs and outputs only. Even more immediate outcomes such as number of young entrepreneurs, who, as a result of this programme has started a successful business and increased their income. The intended outcome of increased share of youth participation in the agriculture industry is also not seen.

However, there are some information on the number of those who have been registered for the programme over the years, number of those who have been given training/consultancy, number of workshops conducted, number of the grants disbursed—all of these are only inputs and outputs.

NAP2.0 document did not include such important outcome and impact statistics specifically regarding the PAM or similar programmes, and the lack of data on the outcome and impacts could be interpreted as a sign of poor uptake of the programme i.e., results are insignificant.

In fact, an adverse outcome is observed. NAP2.0 reports overall decrease in employment in agro sector and that limited youth participation in agro sector is acknowledged as a problem of the sector (thus indirectly suggesting inefficiency of the PAM and the likes).

As for inputs, it has been reported that the PAM under the 11th Malaysia Plan and in support of NAP1.0 resulted in the approval of grants and loans worth RM126 million, and said to have helped 6,969 young agropreneurs in starting and growing their agricultural activities. However, we have not found more information to understand the outcomes and impacts of these expenditures and activities, aside from some anecdotal evidence of some success stories.

On the other hand, there are several worrying indicators on the status of the issue i.e., lack of youth workforce in the agro sector, by observing key facts and figures. As reported:

- In 2015, it was reported that only 15% of the workforce in the agro sector were youths. Specifically, it was estimated that the youth participation in the agro-food sector was at 15% of the number of members registered with the Board of Farmers’ Organisation.

- In 2016, only 4.2% of tertiary graduates considered a career in agriculture.

- In 2019, around 10.6% (or 1.6 million) of the approximately 14.8 million workforces in Malaysia are part of the agricultural workforce. The agriculture workforce experienced a decline of 0.5% compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) between 2010 and 2019, at the backdrop of a 2.7% increase in CAGR of the overall workforce in Malaysia.

- There is a clear shift in interest from the workforce, resulting in the insufficient succession from the youth as a replacement for the existing generation of farmers causing the workforce in the agro sector to continue to decline.

- There is also a poor perception of the agro-food sector. There is a prevailing perception among youths that the agriculture sector is a labor intensive sectors with low returns.

The PAM, like many other similar programmes, as a pure example of “Input-Output” culture prevailing appears to place the main emphasis on workshops, training, consultancy, and grant distribution which, as we already know well, are linked to producing workshop-preneurs, grant-preneurs and their likes instead of agro preneurs.

Therefore, to ensure that public funds are spent properly the programmes need to focus on other aspects more directly related to the desired outcomes and impacts for the many. In fact, PAM originally intended to facilitate soft loans, ease land rent, and provide other facilitation needed.

In NAP2.0, this is relatively more comprehensive and proactive. For example, the core policy strategy and action plan 3 under strategy 1 (“Attract and Retain Young Talent”) involve the rebranding of the agro-food sector with modern and smart agriculture, creating an optimum industrial workforce resource through graduate integration into the “real” work environment through internships and apprenticeships, targeted education and innovation competition, and the development of new management models to improve productivity.

This is aligned with what EMIR Research mentioned in past articles in making agriculture “sexy” again.

Obstacles and challenges

As said, as far as mentioning all the right things and ensuring the latest buzz words and trends, Malaysia’s policy documents rarely fall too short. Our challenge is always implementation and sustainable execution.

One of the greatest obstacles in ensuring a proper implementation is the absence of structural reforms therefore overall agro sector, its dedicated ministries and agencies as well as specific intervention programmes continue to suffer from the governance problems such as corruption, inconsistency in policies and their implementation (due to conflicting interests not necessary aligned with the national interests) and potential leakages and mismanagements.

The are other existing and persistent issues to get the interest of the youths. As reported in NAP2.0, there are:

- Participation constraints for youth aggropreneurs. Strict regulations coupled with a less conducive environment results in low participation of young agropreneurs in the agro-food sector. Young agropreneurs also face the challenge of applying for loans. Other challenges include high start-up costs, cumbersome “red tape” or strict regulations preventing the entry of new agropreneurs as competitors in the market.

- Increasing awareness and implementation of widespread mechanisation in the agro sector. Youthsneed to move up the talent supply chain as low-skilled, mechanical and repetitive labour work could be vastly automated.This is evident as despite the decrease in employment, it has been reported that the overall agrofood employee productivity increased from 2010 to 2020, likely due to the increased use of automation technologies and techniques through mechanisation and automation for food production activities.

- Income and productivity non-competitiveness in the agro sector: It has been reported that the annual GDP per employee in the agriculture sector is RM63,345, which is less than manufacturing (RM121,944) and services (RM82,488). Furthermore, on average, agricultural workers earn low or uncertain income compared to the average national income. In 2018, the average income for agricultural workers was reportedly RM1,865, whereby the national average was RM3,087. Additionally, the subsector saw the average monthly income decreased between 2015 and 2017 even though it saw an increase in prior years (2010 to 2015), indicating a shrinking value generated in the industry.

Next steps

Involving youth in agriculture would require certainly more than just providing workshops, consultancy or grants. To be able to effectively address such an issue the national agricultural policy should include at least the following initiatives/action plans:

- Institutionalise the Input-Output-Outcome-Impact framework as a solid basis for intra-ministerial / intra-agencies co-operations and interventions;

- Localise or redirect the production for all parts (upstream and downstream) of the food supply chains for critical-self-sufficient (CSS) items (this is to protect local entrepreneurs from external supply-chain shocks);

- Create a single national supply chain management data platform for CSS-designated food items (to eliminate the issue of the middleman and monopolies);

- Set the universities that have land as national flagship universities to spearhead research and collaboration with a focus on AgriTech, circular economy and regenerative agriculture principles;

- Provide various financing options with a focus on start-ups and MSME segments, and technology adoption within the agriculture industry: Malaysia’s sovereign wealth funds (Khazanah and EPF), innovative smart financing or viable commercial banking sector options;

- Ensure land availability for agricultural activities: limit land ownership while introducing rent ceiling and permanent rental contracts for small farmers;

- For the AgriFood flagship universities align key performance indicators with the number of research that reaches the commercial stage;

- Provide critical infrastructure and services for moving food around from farm to market;

- Ensure that children from the school or even from the kindergarten level are introduced to the concept of 4IR agriculture for them to learn that there is nothing 3D (dirty, difficult, dangerous) about modern agriculture but it is fascinating and exciting. This is what is successfully done in other countries such as Japan, South Korea, and Singapore where government begins to inculcate change they want to see in society a few years down the road through curricula from kindergarten to universities.

Certainly, the future of the agriculture sector is the youth. Producing highly skilled food agri-techpreneurs at scale is one of the major trends among the countries that exhibit stellar performance in the Global Food Security Index. And this also includes taping into the pool of massive youth unemployment that Malaysia has.

After all, Malaysia has massive youth unemployment and underemployment, vast unutilised/underutilised land (and for modern farming, it does not necessarily need to be fertile land as modern farming can be done in polybags and a completely controlled environment) and captive market demand (our food import is massive every year).

All we need to do is too pull these key ingredients together into a sound strategy done right — with the clearly set Input-Output-Outcome-Impact links and metrics.

Dr Rais Hussin and Dr Margarita Peredaryenko are part of the research team at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.