Published by BusinessToday, image by BusinessToday.

As part of institutional and political reforms, the Madani government under Prime Minister (PM) Anwar Ibrahim has also been targeting what’s known as the super-elites – who are the best embodiment of what Professor E Terence Gomez has aptly termed as the “nexus of business and politics” in the Malaysian context.

These elites who are “a cut above” the other elites can trace their origins back to the first Mahathir administration during which crony capitalism first made its impressionable mark.

This was during the heydays of corporatisation or “piratisation” as detractors, including the indomitable veteran politician Lim Kit Siang, would term it.

The privatisation of state-owned assets and increasing intervention and participation in the economy, as proxied by the explosive growth of the stock market, resulted in Umno’s rapid transformation into the patron and benefactor (as well as beneficiary) of corporate players.

The entanglement between politics and corporate interests became more pronounced as the economy took off on the back of intense industrialisation and the stock market boom during the 1990s – which was also partly made possible by the high savings rate of the population including the role played by the Employees Provident Fund (EPF).

Since the post-first Mahathir administration (1981-2003), these elites have continued to expand their financial and business interests across many sectors – telcos, utilities, construction, commodities, food, etc. and other strategic sectors which are normally not governed by typical competition laws (as embodied by the Competition Act 2010) such as the airlines industry (as of March 1, 2016).

This means that the economy has become dependent on these elites whether directly or indirectly, i.e., through proxies and in turn their intermediaries.

It includes monopolistic and cartel-like powers exercising unrivalled/unchallenged control over various parts of the economy both via State concessions and market dominance.

As such, the capacity of these super-elites to cause some disruptions or affect the economy, directly or indirectly, can’t be underestimated.

For example, there have been some speculations that super-elites could have been partly responsible for the downward pressure on the RM, whether intentionally or otherwise.

Their financial firepower can also be readily epitomised by the hoarding and stashing of both legitimate and ill-gotten gains overseas (through e.g., money laundering methods) in the form of foreign currencies and other financial assets (liquid: e.g., bonds, shares, derivatives; illiquid: e.g., real property) – representing illicit outflow of funds.

Historically, these are reasonably assumed “co-variant” indicators (of the downward pressure on the RM – which can be attributed to the (“arbitrary”) pegging of our currency at RM3.80, representing a wide margin from the initial RM2.50 just prior to the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997/98 albeit the figure represented the “median”, i.e., middle-plot of the downfall range towards the RM4.50/75 mark).

Much of the proceeds from illegal gains leaked overseas have been funnelling into off-shore accounts, especially in tax havens such as the Cayman Island and British Virgin Islands (BVI) as demonstrated by the Panama and Pandora Papers exposés, among others.

As such, the super-elites have been primarily responsible – due to the nature and extent – for the diversion and hoarding of some of the country’s wealth that could have been more equitably distributed.

Better late than never, the government needs to undertake a pre-emptive strike, to avoid any negative impact on the economy via the downward pressure on the RM and/or continuing outflow of funds (through divestments, transfers to off-shore accounts, etc. or illicit means), in addition to implementing the reforms which are necessary to move the country forward.

In particular, the reforms that are integral to strengthening the roles of our government-linked companies (GLCs) and the Bumiputera empowerment agenda.

By and large, the public understands and appreciates the actions of the PM.

He has clearly and unequivocally laid out the reasons why – albeit at times with a somewhat “politicised” tone.

As alluded to, the looting and plundering of the nation’s wealth over the decades can be attributed to the super-elites (among others, to be sure). The crackdown via criminal charges shouldn’t deter investors and create negative perception among external observers.

In fact, on the contrary, what the PM is doing is precisely rehabilitating and elevating Malaysia’s reputation and image in the international community which had been severely dented since the 1MDB scandal.

Understandably, certain segments of the population as embodied by both the reformist detractors (represented by the “liberal intelligentsia”, for example) and the Opposition are decrying the high-profile crackdowns as selective prosecutions to serve the political needs and vested interests of the government of the day.

So, the PM must undoubtedly do more to comprehensively address public perception and the reality of the systemic and institutional rot of corruption in the economy and State apparatus (please refer to the policy recommendations by EMIR Research in “Pragmatically Elbowing Malaysian Corruption and Leakages”, July 28, 2023).

In light of this, EMIR Research would like to reiterate our call for the establishment of the Truth, Recovery and Amnesty Commission (TRAC) – to track and recover the monies which’re so needed for the development of the nation. Modelled after South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), TRAC aims to bring about an effective and sustainable closure to the decades of entrenched corruption in Malaysia (parallelling the role of the TRC in addressing the legacy of the apartheid regime).

Through TRAC, individuals who voluntarily return the criminally obtained funds, mansions, moveable and/or immovable assets, etc. can be accorded some form of amnesty from prosecution subject to certain restrictions such as, for example, limitations on appointment to public office and participation in public service (political, administrative).

Individuals who choose to undergo the investigation and prosecution processes and are eventually found guilty of corruption must be brought to justice with the option for amnesty available upon returning the misappropriated assets.

Given the enormity of accumulated losses (referenced in EMIR Research article, “Malaysian Monetary Loss to Corruption and Leakages – RM4.5 trillion over 26 years”, May 10, 2023 – note that these estimates are very conservative and the 26-year period was chosen based solely on available data), the recovered funds (if realised even in part) would be a substantial source of revenue to more than plug the gap in government expenditure needs whilst enhancing the goal of fiscal recalibration towards productive purposes (including not least increasing the scope of targeted subsidies).

Apart from ensuring the recovery of illegally procured funds and prevention of such transactions which can then (re)allocated/channelled towards productive and beneficial deployments for the sake of the MANY, fighting corruption sends a very powerful and unambiguous signal that we’re serious about placing the country on a sustainable trajectory in the preservation and conservation of our natural, physical and financial wealth and resources for future generations.

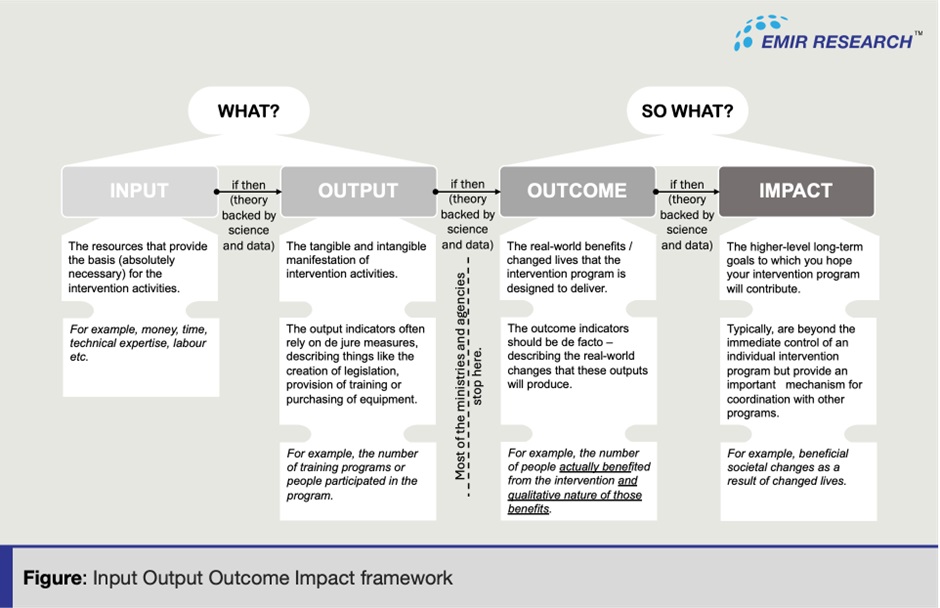

In ensuring these sustainably produced long-term outcomes for the nation of which the crusade against endemic corruption is an essential and integral aspect and pre-condition, EMIR Research continuously emphasises on the critical imperative of institutionalising the Input-Output-Outcome-Impact (IOOI) framework across all of government – ministries, agencies and also the GLCs – as the (lead) enablers of the political, administrative and economic systems, structures and grids.

The IOOI framework (see the Figure below) is a dynamic system (solely based on science and data) of the entire causal pathways from inputs (constrained resources/capital) to outputs (tangible and intangible manifestations of intervention activities) and through to outcomes (real-world benefits, e.g., socio-economic advancements) and finally to impact (higher-level intergenerational goals, e.g., increased levels of household savings relative to incomes).

In other words, when policymakers embark on an initiative, they must convince and provide assurance to the public (taxpayers and the wider rakyat) that there’s a solid basis in the form of empirical evidence and an established body of scientific knowledge to believe that using an n amount of inputs (resources) on specific outputs will result in the desired outcomes and intergenerational impacts.

We’ve seen this being implemented gradually – beginning with the Public Finance and Fiscal Responsibility Act (2023) at the macro-level.

Holistically speaking, the Madani government is, therefore, on the right track.

Notwithstanding, reformist critics of the PM are presently disenchanted with the pace and extent of the reforms and have taken to expressing their opprobrium at his anti-corruption agenda as merely political posturing and “one-sided”.

The discharge not amounting to acquittal (DNAA) of Deputy PM Ahmad Zahid Hamidi as well as that of some of the charged Umno leaders such as ex-Menteri Besar of Negeri Sembilan Isa Samad have infuriated many quarters.

Erstwhile supporters, especially, had hitherto harboured high hopes and were optimistic of genuine reforms once again in the country since the short-lived Pakatan Harapan (PH) experiment in the aftermath of the 2018 general election. The DNAAs of these Umno leaders have quickly resulted in disillusionment among many of the PM’s urbanite supporters who have turned around to become some of his most strident/trenchant critics.

To be fair to the PM, he has also carefully and clearly explained the situation behind the DNAA as emanating from the constitutional and rightful prerogative of the Attorney-General (AG) to halt or terminate prosecutions (nolle prosequi) at his sole discretion wherein the reasons may or may not be disclosed.

Under the Federal Constitution, the AG isn’t legally compelled to disclose the advice or reasons for discontinuing the prosecution concerned. As such, there can be no question of any interference by the PM or Cabinet in the matter.

What the PM can do in reassuring the public is to give a guarantee that future institutional reforms will also apply to the office of the AG – whereby the office and role will be separate from the public prosecutor (PP).

Additionally, perhaps the AG could be drawn from among the Members of Parliament, as in the case of the UK, to enhance and bolster accountability and transparency.

Alternatively, as part of the widening and deepening of the corruption dragnet, the Madani government via the Minister of Law and Institutional Reforms YB Azalina Othman might want to consider the creation of a separate Office of Special Attorney-General dedicated to corruption cases (involving high-profiled figures – politicians, civil servant, corporate).

Jason Loh Seong Wei is Head of Social, Law & Human Rights at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focussed on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.