Published by Astro Awani & Business Today, image from Astro Awani.

The imposition of a state of emergency on Jan 12, 2021 doesn’t in any way alter one of the fundamental and indispensable structures in our constitutional and political system, namely the separation of powers (SOP).

SOP is necessary to ensure a) prevention of concentration of powers in the Executive; and b) check-and-balance between the institutions or branches of government, particularly by Parliament and judiciary, again, in reference to the Executive. The first limb has been taken away by the Emergency as embodying the exigencies of time. The second limb remains intact.

Nonetheless, by its very nature and definition, SOP is meant to also enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of governance so that each of the institution or branch of government can run accordingly.

This means, therefore, that limits and boundaries to the powers of each institution or branch of government cannot be symmetrical, practically speaking, or applied according to the abstract and philosophical principle of equal ultimacy more so when Malaysia isn’t and has never been a constitutional republic but a parliamentary democracy ala Westminster-style with roots in parliamentary sovereignty which in reality means sovereignty of the House of Commons that in turn means, ultimately, sovereignty of the Executive-sitting-in-Parliament.

But notwithstanding, we first stress the role and function of judicial review.

It may seem paradoxical that the latter (i.e., second limb) remains substantially and formally preserved despite the former (i.e., first limb) now being suspended albeit not indefinitely – since both are indeed inextricably linked, mutually dependent and correlated.

However, it’s noteworthy that we are dealing with real-world matters where existential tension exists as a matter of nature, and not mathematics or Aristotelian abstract logic of the rule of excluded middle where e.g., either proposition A is true or not, i.e., either/or.

Judicial review, i.e., the inherent power of the superior courts to examine, evaluate and supervise the legal propriety in the exercise of administrative powers by the Executive whether under statute law or, less so, common law (“prerogative”), therefore, remains a constitutional and legal remedy and avenue available to check-and-balance the Executive notwithstanding the Proclamation of Emergency.

This is because as noted by Federal court judge, Justice Zainun Ali, in her landmark decision re the case of Indira Gandhi v Pengarah Jabatan Agama Islam Perak & Ors [2018]: “[T]he power of judicial review was essential to the constitutional role of the courts and inherent in the basic structure of the constitution.

It cannot be abrogated or altered by Parliament by way of a constitutional amendment” (p. 26). She also cited from the case of Lim Kit Siang v Mahathir Mohamad [1987] whereby it’s enunciated that “[t]he courts have a constitutional function to perform and they are the guardians of the constitution within the terms and structure of the Constitution itself”.

Furthermore, in her special address on the occasion of the Lawasia Constitutional & Rule of Law Conference 2019: Constitutional Government, the Importance of Constitutional Structure & Institutions, Chief Justice Tengku Maimun Tuan Mat stated that “[a] corollary to the [SOP] principle is the power of the Courts in judicial review. No Act of Parliament may deprive the Courts of that inherent power. This was what the Federal Court expressly pronounced first in Semenyih Jaya Sdn Bhd v Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Hulu Langat …”.

Secondly, we now come to the limits of judicial review – without in anyway seeking to pre-empt any application for judicial review or influence the outcome there, whether at the initial/preliminary or the substantive stage.

As judicial review concerns itself with exercise of administrative powers by the Executive, there are limits as to its supervisory role and function. In the concrete context of Malaysia, Article 150(8) of the Federal Constitution has already pre-empted any legal challenge to the Proclamation of Emergency, thus representing a “constitutional ouster clause” of sorts. Now, whether this will be considered justiciable (i.e., an issue or matter that can be decided) by the courts remains to be seen – and it has to be said that this isn’t the fundamental legal issue here.

What’s under consideration is whether the nature of the application of judicial review will be politicised – leading to the “politicisation of the judiciary” – something that by way of analogy the judges of the High Court and of the Supreme Court of the UK in hearing the case involving Gina Miller v the Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union were most careful to avoid. Both courts were at pains to emphasise that what’s at stake isn’t the validity of the In/Out (i.e., Brexit) Referendum that took place on June 23, 2016 since that would be political in nature.

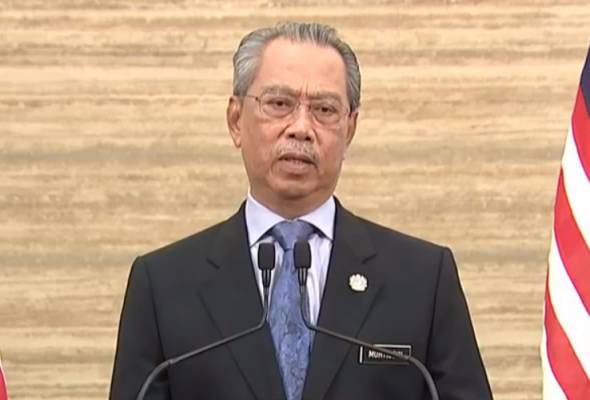

Likewise, it’s hereby submitted, as a matter of legal discourse, that any application for judicial review requesting the court to determine the question of whether it’s legitimate for Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin as the sitting Prime Minister who has lost parliamentary majority to advise His Majesty to declare a state of emergency would or could be inherently political in nature and therefore goes beyond the capacity of judicial review – which to reiterate limits itself to the question of administrative exercise of power principally in the form of procedural impropriety and irrationality (i.e. substance of the logic behind the decision-making process, again with emphasis on the processes and therefore also the procedures which paves the way as a matter of natural development to the situation where only in very exceptional cases would the decision itself be open to legal challenge) as per e.g., the case of Rama Chandran v Industrial Court [1997].

In short, it’s submitted the court will inevitably be “dragged” into determining the question of whether Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin has lost parliamentary majority – which is purely an issue of political reconfigurations, manoeuvrings, and arrangements. This is significantly to be distinguished from the role of the Election Court in determining electoral offences and irregularities and improprieties under the Election Offenses Act 1954.

Following on from this, judicial review, therefore, has traditionally and conventionally shied away from pronouncing on matters relating to “high policy”. High policy refers to the decision by the Executive, both at the foreign and domestic levels, based on the Constitution, statute law and common law. For example, the proposed ratification of an international treaty such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) or the formulation and implementation of a stimulus package cannot be legally challenged simply because it would be inimical to local businesses and increase the fiscal deficit or debt level, respectively.

In the case of the UK, due to parliamentary sovereignty, it refers to Executive decisions falling into the ambit of the Crown prerogative as per the R v Secretary of State for the Environment ex parte Nottinghamshire Council [1985] where Lord Scarman made the following astute observation that it isn’t “constitutionally-appropriate, save in very exceptional circumstances to intervene on the ground of ‘unreasonableness’ [or any other grounds]” just because it’s not politically palatable to certain parties.

Any application for judicial review questioning the legitimacy of the Emergency on the grounds that the grounds for such Proclamation doesn’t actually exists, therefore, is surely a purely political and policy question which the courts are not in a position to intervene for that would ironically be violating the principles and rationale for the SOP in the first place. More to the point, it would also be tantamount to questioning the competency and wisdom of His Majesty as a bulwark of the Constitution and fourth branch of the government.

In the final analysis, perhaps the only ground which an Emergency could be challenged, rightly so, would be the time-frame. This Emergency has one – which is limited to Aug 1, 2021 or until the Covid-19 epidemic can be brought under control or has subsided. And a special bi-partisan and inclusive committee is being set up to determine on the question of the latter.

As to the requirement that the Emergency Proclamation be tabled before both Houses of Parliament, it’s undoubtedly true that the Constitution assumes the situation and provides for it. But the provision of Article 150(2B) & (3) presuppose Parliament as currently sitting or in session which is clearly not the case when the Proclamation of Emergency was promulgated.

It’d be interesting and exciting to observe the applications for judicial review in the coming days and weeks. But this should be appropriately “compensated” and “counter-balanced” with a political sabbatical.

Jason Loh Seong Wei is Head of Social, Law & Human Rights at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.