Published in Focus Malaysia and MalaysiaKini, image by Focus Malaysia.

Is the fact that cession payment had continued to be made to the (supposed) heirs of the Sulu Sultanate up until 2013 as a result of the Lahad Datu incursion materially relevant at all to their case for compensation, etc.?

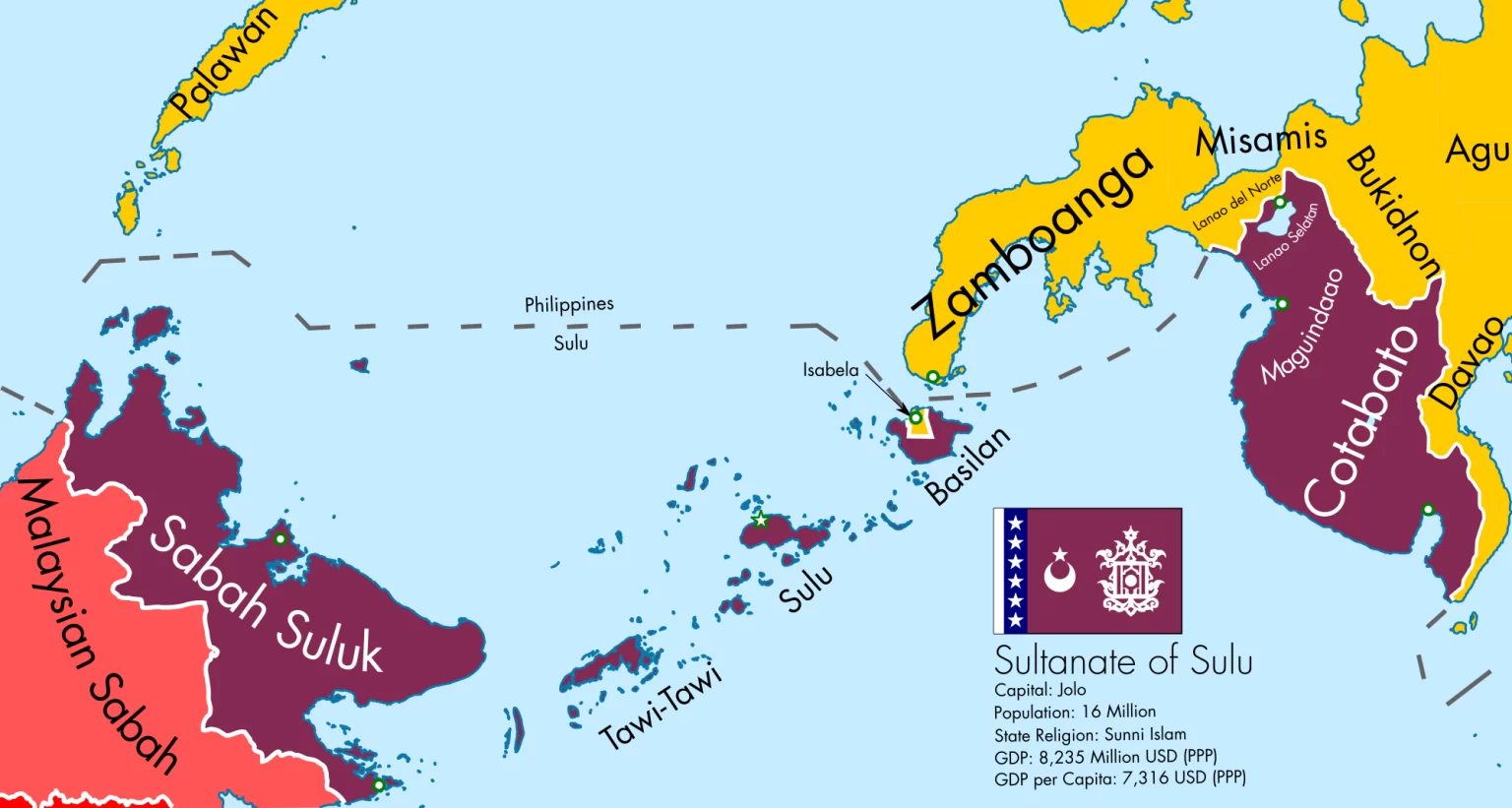

Some would argue that Malaysia’s “resumption” of the cession payment of RM5300 under the terms of the 1878 Agreement signed between Sultan Mohamet Jamal Al Alam with Baron von Overbeck and Alfred Dent constitutes an explicit (if not, implicit) recognition of the “lease” theory, i.e., that Sabah (then North Borneo) was only leased – and not given up – to the North Borneo Chartered Company (NBCC).

For otherwise, why continue to make the payment, especially after the fact that it actually was discontinued by the NBCC in 1936 when Sultan Jamalul Kiram II died that year without leaving an heir?

In other words, the act of making payment would by default presuppose and imply that it’s not voluntary but a legal obligation and liability of the NBCC and, by extension, the British colonial administration and finally the Government of Malaysia (GOM).

And hence, the cessation of the cession payment in 2013 serves only to attract the sum of compensation as awarded by the French Arbitration Court in Paris via the person of Dr Gonzalo Stampa on May 5, 2021 for the sum of USD14.92 billion (approximately RM62.59 billion). The initial claim was USD32 billion – which comprised both the unpaid cession sum as well as the gross reserves value for oil and gas in Sabah’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

Notwithstanding, on June 29, 2021, at the request of GOM, the Madrid Court revoked the appointment of Dr Gonzalo Stampa as arbitrator. This was followed up with another ruling by the Madrid Court on October 13, 2021 which specifically declared that Dr Stampa lacked the jurisdictional faculty to make that ex parte (i.e., without the presence of the other party) decision on behalf of the French Arbitration Court which has since been rendered null and void.

According to Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department (Parliament & Law) Datuk Seri Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar, GOM had also filed a criminal complaint with the Spanish Attorney General against Dr Stampa in protest against his non-compliance with the Superior Court of Justice of Madrid’s decision alongside the irregularities of procedures, injustice, and contempt for the rule of law on December 14, 2021.

An appeal has also been made by GOM to revoke the exequatur order and an application to stay its implementation. On December 16, 2021, the French Court of Appeal allowed the Malaysian government’s application for the stay of the exequatur order issued on September 29, 2021 pending an appeal.

The exequatur order simply means that the French Arbitration Court has the authority and jurisdiction to enforce the award with legal effect outside of France, i.e., on GOM.

As pointed out by Datuk Seri Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar, the May 25, 2020 preliminary or partial ruling in Madrid by Dr Stampa proceeded on a very faulty assumption to begin with. That is, the 1878 Agreement was an “private lease agreement”. This is, of course, contrary to the facts of the matter as the 1878 Agreement was signed between one party which claimed sovereign right and ownership and the other party intending to do so over the same territory.

It’s simply irrefutable that the administration of the NBCC has all the hallmarks of a government, i.e., sovereign entity – which gainsay the preposterous argument that it’s purely a commercial transaction.

As to the argument – accepted yet again by Dr Stampa on February 28, 2022 in defiance of his revocation and disqualification (see page 94 of the Final Award) – that the sovereign can also behave as private citizens (acta de iure gestionis) and, therefore, no legal immunity is afforded is simply untenable.

For that would effectively mean that there would have been, at least, some semblance of Sulu Sultanate or Spanish sovereignty in North Borneo.

For example, there would or ought to have been some form of a hybrid legal or even administrative system or both. Tax revenues would have been partially diverted to the Sulu Sultanate in addition to the cession payment and, by extension, Spanish Philippines.

As we all know, taxation is one of the fundamental features of sovereignty – as it’s underpinned by coercive power and right.

Taxes drive the currency as issued by the State, which is also another feature of sovereignty.

None of which ever existed.

Furthermore, the post-1963 cession payment was denominated in the ringgit – that is the currency of Malaysia as a sovereign entity.

No complaints or grievances have ever been filed to change that arrangement by the heirs of the Sulu Sultanate.

It simply means that the claimants (so-called heirs and successors-in-title of the Sulu Sultanate) and the arbitrator have confused the procedural with the substantive aspects of the 1878 Agreement. The procedure by which the 1878 Agreement was to be executed would be the cession payment (originally 5300 Spanish dollars). The substantive matter of the 1878 Agreement pertains to the transfer of North Borneo from one sovereign entity to another.

Again, that the NBCC was a sovereign entity in its own right was neither novel nor absurd – since its counterpart in India had been the English East India Company before the Crown assumed direct control to become the British Raj by virtue of the Government of India Act (1858).

Of course, such a case wasn’t confined to the British alone. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) operated in a similar fashion – in Melaka and the then so-called East Indies (modern-day Indonesia).

There’s no denying that NBCC, at all material time, perceived itself as a sovereign power and had intended to act accordingly (acta de iure imperii).

As to the Sulu Sultanate heirs, it’s immaterial whether 1936 marked the time when there were no longer known heirs or that the family line still continued after that.

What finally matters is that cession payment was never a recognition of sovereignty – as the behaviour of NBCC and subsequent legally-binding agreements (namely the Madrid Protocol of 1885 and the Confirmation of Cession Deed of 1903) demonstrate.

Jason Loh Seong Wei is Head of Social, Law & Human Rights at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focussed on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.