Published by Malaysiakini, Malay Mail, New Straits Times & Sin Chew, images from Malaysiakini.

In a world of words, the sabre-rattling in any theatre of conflict can get all sides to the very edge of war. Thus the recent fiery exchange between the US and China, if not half of the European states against Beijing, should be handled with extreme caution.

Wiser counsellors/advisors in the state council of China, such as Shi Chunlong, not excluding the Chinese ambassador to Washington, Cui Tian Kai, have all urged the “wolf warriors” in the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs to tone down their rhetoric.

Among them Chinese spokesperson such as Hu Chung Ying, Geng Shuang and Zhao Li Juan, all of whom are the subordinates of Cui.

However, systems of nuclear alert such as Defcon I to V, or defence confrontation I to V – with V being the most dangerous stage, simply does not exist here to alert anyone of the danger of the situation.

In the South China Sea, where the maritime bourne trade is worth trillions each year, according to William Pesek of Bloomberg, it would be tragic to see all sides come to a blow.

As recent as a month and a half ago, even the Malaysian navy, for the first time in its history, had to resort to the act of self-defence to protect its Exclusive Economic Zones, where one illegal Vietnamese fisherman died.

To the credit of the media of Malaysia and Vietnam, neither side sensationalised the issue. If they did, tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of people would throng the streets of major cities in Vietnam and Malaysia to demonstrate their nationalistic fury.

China is capable of such self-restraint too when some of its detained illegal fishing vessels were detonated by Indonesian President Joko Widodo. China did not show any angst or collective national anger when China’s vessels together with that of other countries that had encroached into Indonesian waters were sunk in front of the international press.

But such self-restraint alone is now becoming increasingly tenuous and indefensible. Chinese military modernisation, its resurgence as a maritime power, is almost complete.

Last month, the second aircraft carrier was completed in Shandong province in the northeast of China. All military analysts worth their grain of salt know that a second aircraft carrier is meant to back the first in the event of an actual war.

In the case of the US, when tensions rise with North Korea, the third and seventh fleet of the Indo-Pacific command based in Honolulu, Hawaii will begin plying the waters of the East and South China Sea, either together or with one stopping over in the deep port of Changi, Singapore. This is to show that in the event of any friction that leads to war, the US is cocked and ready.

With the proliferation of Covid-19 in one of the fleets, if not both, Washington has learned to keep their sailors socially distanced.

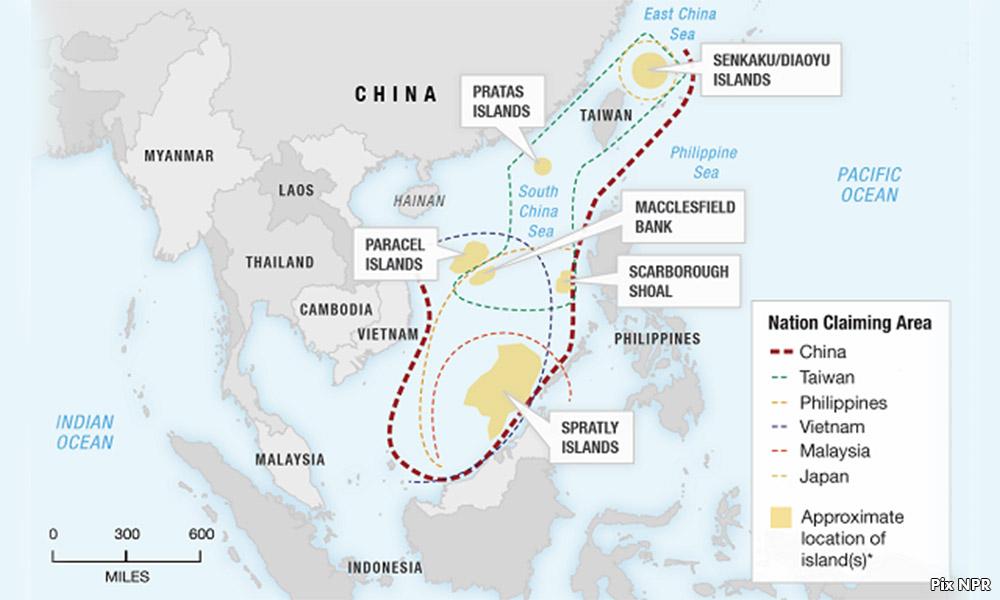

China could take advantage of this adverse situation to consolidate its claims on the South China Sea. But granted that the claim is almost 90 percent of the contested waters, Beijing should know that it is morally and legally obliged to show all evidence that the South China Sea belongs to them.

In fact, countries like Vietnam and the Philippines are just as responsible. This is because the South China Sea was once demarcated as a small, though significant, maritime area by the Manchu Dynasty in China.

A Chinese cartographer who worked on China’s legal predominance was the first to produce the 11-dash line in 1947 to mark its territory on the South China Sea, when Guomingtang was in power in Beijing.

When the Chinese Communist Party defeated the Guomingtang in 1949 – leading to the discourse in Washington as to who “lost China” – it was clear that the US was not happy with the situation then.

The US restored some semblance of normalcy with China marked by events such as in 1972 when former US president Richard Nixon made an exceptional visit to China to consolidate ties to work closely with chairperson Mao Zedong, in forming a two-front party against the Soviet Union.

Under the Shanghai Communique, both sides would “acknowledge”, but not recognise, Taiwan as part of the Republic of China, while the mainland would be regarded as the People’s Republic of China.

By 1979, the normalisation of Sino-US conflict would further continue, with the Taiwan Relations Act which obliged the US to come to the defence of Taiwan too.

Between 2001 and 2002, both the Republican and Democratic administrations would help China to become a member of the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

Between 2002 and 2015, economists in China and the rest of the world would agree that China enjoyed the biggest spurt in growth, perhaps as much as 300-400 percent in its per capita income. Globalisation obviously worked in China’s favour, which is why over the last decade alone, some 800 million Chinese have been lifted out of absolute poverty.

Given all the gains, China should understand that the world does wish it well; although there are another 600 million Chinese people who have been promised by President Xi Jin Ping to be redeemed through its anti-poverty campaign.

But when things like China Cables (a collection of government documents) began to leak from China to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalism (ICIJ) in November 2019, which was further reported in the New York Times, where highly classified internal communication had Xi urging the Iocal Communist officials to “show no mercy” on Uighur Muslims, Southeast Asians are inclined to wonder if this is also the policy mentality of China on the South China Sea.

Does that mean Xi, whose thoughts are included in the Chinese Constitution, whose role, in fact, endowed him with the right to rule China forever, may be surrounded by a motley group of hawkish policy advisors too?

On Xinjiang, the Chinese foreign minister has been known to snap back at international journalists for raising any questions of Xinjiang. His usual retort, verging on total arrogance, would often be: “Have you been to Xinjiang? Do you know we have raised 800 million people out of poverty?”

If the top decision-makers of China like Wang Yi – who is in the Politburo of the top 25 members of China – continues to conduct himself in such a way, then the rhetoric of China would be “not one dash line less”.

Yet, history showed that the 11-dash line on the map of China’s South China Sea, had been unilaterally reduced by two lines by Mao, when the Vietnamese Communist Party defeated the French in Dien Bien Phu in 1953.

The fact is none of the states that are currently at odds with China over the contested waters of South China Sea, are in conflict with any foreign adversaries of China at this stage, nor do they want to be. Thus China cannot use the carrot-and-stick or reward and punishment approach on Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam or for that matter, Taiwan, who also claim the South China Sea.

Granted the current situation now, where China and the US are locked in various kinds of conflict, not excluding Japan too over the East China Sea, and India up in the Himalaya, nor should one exclude China’s deteriorating relations with Australia and Canada, it is clear that China’s diplomacy – whether by design or default – has led itself into a situation where it is increasingly seen not as a progressive or status quo power, but a revisionist one.

The latter implies China is out to upend the whole global public order.

As Professor Graham Allison pointed out in 2016, when the world confronts 16 sets of such conflicts, they will find themselves in the “Thucydides Trap” where the whole world becomes afraid of China, which in more ways than one, is a closed society in the upper echelon of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

China has all the methods or vocabulary of self-introspection in CCP since its founding in 1921.

By 2021, if not sooner, China has to concede that its hardened attitude on the two seas is a cause of great concern since 2006 when former Japan prime minister Abe Shinzo came up with the concept of the Indo-Pacific to urge all countries in the Indian Ocean, South China Sea and the Pacific Ocean to think “big” on how to handle China’s growing stature. As of May 31, 2019, the US Department of Defence has come up with the Indo-Pacific Strategy.

Australia also has a similar Indo-Pacific paper, while Asean has the Asean outlook on Indo-Pacific, where the Indian Ocean and South China Sea are seen as “one contiguous water”.

As things stand, the world is roiled in a pandemic. Thus the tensions in the South China Sea can be momentarily overlooked. But if China were to seize on this strategic confusion to push its claims deeper into the area, more and more countries would be naturally alarmed.

Not unlike the fear of the Hong Kongers in the break down of the “One Country, Two Systems”, many countries that want to trade with China will also begin to wonder if China has become a super assertive power that needs to be counterbalanced in every way that Taiwan had always advised. If the latter were to happen, the concept of one Pacific Asia would be broken into pieces.

By extension, the whole world would in due course also become afraid of the true designs of Xi’s “Belt and Road Initiative,”. Is it a form of predatory economy or debt trap diplomacy? The world does not have to concur with the West that the Belt and Road Initiative can become a Chinese labyrinth where it is easy to go in and almost impossible to come out. But since the end of 1945, no country has ever wanted to be colonised by the East or West.

Since 1989, which marked the end of Cold War, no one has wanted to see a second one, especially China which has constantly urged the US to get out of its “Cold War” mentality.

But the West and the rest of the world cannot let down its guards on China if the opening gambit of China is to claim 90 percent of the South China Sea. Justified or not, that in itself is a form of post-modern or pre-modern colonialist thinking.

There must be a restraint approach. Top presidential advisors of China, such as General Luhut Pandjaitan of Indonesia, has also urged China to do the same. Emir Research does not want things in the South China Sea to go awry too. Let’s work together to pin down the pandemic.

There is no need to have a difficult relationship with the US or the West to navigate through a world sickened by the pandemic, which according to the World Health Organisation (WHO), can be one “global gigantic wave”, with no summit to flatten. This is as dire a warning as any international health entity can give.

Having missed out on the chance to invite WHO into China quickly to look into the eruption of Sars Cov II virus in December 2019, it is high time China does not merely produce high-speed train or potentially a high-speed vaccine by SinoCan, but also high-speed diplomacy based on reconciling their differences with all.

The Malaysian and Indonesian culture is based on “mutual forgiveness”. But lurking behind this mutual creed is total contempt for those who do not take this creed seriously, or, knowing how to say “we are sorry, let’s start again”.

If this pandemic had started in South Korea or Japan, perhaps their diplomats would be more and more contrite. China, regardless of its size, has to learn how to be more humble. Claiming 90 percent of everything in the South China Sea is a sign of how China has made the wrong move.

If Vietnam, or for that matter Taiwan, were to adopt the same attitude, all the member states of Asean would chastise them too, as this is a no brainer to begin with.

Dr. Rais Hussin is President & CEO of EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.