Published by BusinessToday & AstroAwani, image by BusinessToday.

The agricultural sector, pivotal to the economies of developing nations, was poised for significant transformation during 2016-2019 with the emergence of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). Concurrently, the global crisis of the COVID-19 outbreak exposed many nations’ vulnerability in terms of their national food security.

More challenges—be it the next “disease X” outbreak, new geopolitical crises, or ravaging climate change—are expected in the future, so we must embark on a trajectory that will allow us to be resilient in our ability to feed ourselves.

Various global research outlets estimate that by 2050, the global population will increase to 9.2 billion, the urban population will rise by 66%, arable land will decline by approximately 50 million hectares, global GHGs emissions (source of CO2 promoting crop disease and pest growth) will increase by 50%, agri-food production will decline by 20%, and eventually, global food demand will increase by 59 to 98% – posing an imminent threat to food security and adequate food availability.

In other words, demand for food is growing profoundly while the supply side faces serious constraints in land and farming inputs. Constraints on agri-food availability and corresponding self-sufficiency levels (SSL) highlight the limitations of existing capabilities, compounded by ever-growing demand. This is precisely where agronomy is being revolutionised through 4IR technologies.

4IR aggrotech is a prerequisite and necessary condition for food security. That is why it is unsurprising to see among those leading the Global Food Security Index countries like Finland, Ireland, The Netherlands, Austria, Germany, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea. These countries have long pledged technology to serve their societies in an all-encompassing way under the umbrella of “Society 5.0”. This, of course, includes such an essential aspect of human existence as the ability to put food on our tables.

A closer analysis of the leading countries in the Global Food Security Index reveals that they all focus serious efforts on boosting agri-food technology. They unanimously place hi-tech farming, precision engineering and circular economy principles as the cornerstone of their national food security strategies.

Other common trends among these countries include the following:

- Distinctive national food security strategy with a streamlined ecosystem of dedicated government ministries and agencies.

- Spearheading efforts toward food self-sufficiency – We must heed this trend, which suggests a potential significant reduction in supply (as well as demand) from other nations. It is evident that proactive prioritization and development of local agri-food markets are not only prudent but essential.

- Heavy investments in 4IR aggrotech research and development (with a focus on commercialisation).

- Heighten focus on smallholder farmers.

- Building vibrant and healthy ecosystems around the local agricultural sector infused with tech, including producers, financiers (including innovative fintech solutions to support small producers), policymakers, educators, and even consumers.

- Venture into the area of vertical complete control environment farming. Although it’s true that countries with limited land or water resource availability are venturing quicker into farming or aquaculture techniques and technologies that maximize output from minimal space, other nations also realize how a growing population can outpace food supply, exacerbated with reduced arable land, increased pollution of waterways and water resources, soil nutrient leaching, increased public awareness on health and climate change issues.

- Preparing local agri-specialists at scale.

- Making agri sexy for the youth again.

- Reduction of food loss and waste through innovative waste management and recycling practices.

- Recognising the energy-food-water nexus.

- Regenerative agriculture.

These trends are a loud and salient recognition of a very challenging future we will face soon on a global scale—immense pressure is already being felt to increase crop yields, minimize costs, reduce waste, and maintain process inputs. Only moving along these trends for our own national food security will guarantee us a more or less resilient future!

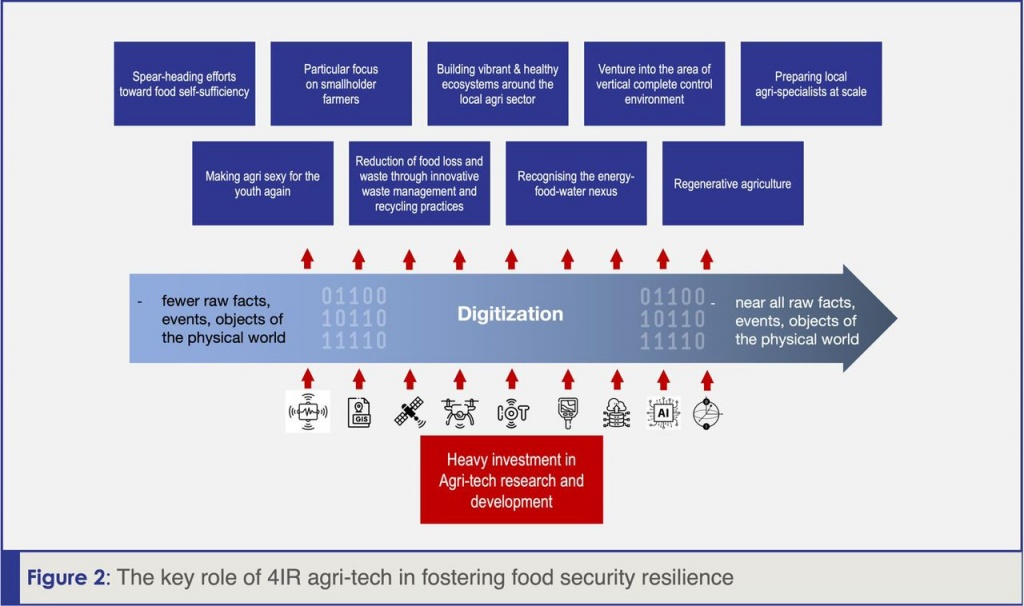

Upon careful analysis of these trends (Figure 1), it becomes apparent that digitalization and digital transformation of the agricultural sector serve as the cornerstone, enabling and supporting all other trends (Figure 2).

Other nations’ profound focus on smallholder farmers also deserves attention. This is also the SDG goal (SDG2.3 – double the productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers), which, surprisingly, given all the SDG hoo-ha, no one is talking about.

Recently, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the International Telecommunication Union called for good practices and innovative solutions to advance the digital transformation of agriculture in Europe and Central Asia. According to the report, they received 192 applicants from 36 countries in the region. Notably, the majority of the 171 practices received, about 84%, focused on improving the livelihoods of smallholder farmers.

This is unsurprising.

Firstly, given the complexity of the 4IR agri-tech transformation evident in pioneering applications, it’s logical to initiate the implementation of novel solutions at micro-farm levels, gradually scaling up as needed.

Furthermore, empowering Malaysia’s small landholders to directly benefit from their land’s produce on a national scale could not only ensure national food security but also address digital inclusion and income inequality, propelling the country beyond the middle-income and low GDP trap.

Instead of consolidating smallholders into large estates, we should empower and support them to become independent agricultural producers with the help of 4IR agritech and fintech. Absorbing their land into larger estates would exacerbate wealth concentration and contribute to the all-feared “technological unemployment” at the back of 4IR in our country.

In contrast, by empowering a significant number of individual farmers to harness the potential within their grasp, we foster widespread equitable wealth distribution and economic independence on a national scale!

Promoting fair and equitable access to 4IR agri-tech is an ethical imperative, as disparities in access to these technologies often worsen existing inequalities.

Conversely, ensuring fair access will result in increased incomes and enhanced livelihoods for smallholder farmers, thereby contributing to poverty alleviation and rural development.

Another profound lesson learned from the pandemic is the indispensable role played by smallholder farmers. Their ability to continue operating during the crisis (unlike large estates) underscores their paramount importance to the country’s food security resilience.

Also, according to global statistics, more than two-thirds of the world’s food is produced by smallholder farmers. However, they suffer from middlemen, lack of finances, etc. This is why we have such expensive food!

Therefore, the focus on smallholder agri-business has yet another appeal to the government. With many farmers across the nation enjoying higher incomes and collectively bringing their produce to the market, there would be downward pressure on food prices, provided, of course, there is sufficient protection from foreign food suppliers.

Lower food prices would result in lower food expenditures as a share of overall household spending, thus leaving a larger portion of the national income available to be spent elsewhere. This has far-reaching implications, such as increased aggregate demand for other industrial goods and services (including the demand for local 4IR technologies and hence deepening industry and reduced unemployment and underemployment), soaring national GDP, increased political stability, and overall techno-socioeconomic progress and well-being of the nation!

Furthermore, witnessing the significant increase in incomes resulting from the infusion of technology into agriculture, as consistently demonstrated in global pilot slides, is likely to attract the interest of young people towards this sector. Consequently, we may anticipate a reduction in youth unemployment and underemployment, addressing one of the crucial issues facing our nation.

Regarding incomes, consistent figures are observed regardless of the farm size: yield increases by up to 30%; water usage reduces by up to 30%; pesticide use decreases by up to 50%; profitability rises by up to 20%; post-harvest losses decrease by up to 20%; and though challenging to quantify, there is consistently a significant improvement in the quality of produce.

Note again: these figures are achievable regardless of farm size (refer to “4IR enabled farmers: Solving national food security” for the proof-of-concept pilot study)—this is the equalising power of 4IR!

All in all, as we witness again, the application of the 4IR in the agricultural sector underscores its role as more than just technological progression; it signifies a comprehensive societal transformation, necessitating a nuanced exploration of its opportunities, challenges, and ethical implications. When implemented effectively, it offers numerous unprecedented opportunities for substantial and rapid progress in our nation. What’s essential is demonstrating readiness to ensure resources are allocated where most needed, with technology serving as a vital tool in this endeavour.

Dr Rais Hussin is CEO of Technology Innovation Park Malaysia (MRANTI), a government agency aimed at accelerating the demand-driven R&D in technology, positioning Malaysia as a nucleus for innovation and a leading technology producer nation.