Published in Astro Awani, The Star, MYsinchew & theSundaily, image by Astro Awani.

Digital sovereignty is defined as independence in the field of digital technology or, as World Economic Forum puts it, “the ability to have control over your own digital destiny – the data, hardware and software that you rely on and create”. However, this narrow definition does not even begin to paint the importance of this term and why it should be the number one agenda in the national plans by all the countries pursued simply relentlessly and hurriedly.

In generalized management theory terminology, an object loses its sovereignty when it becomes simply a subject of a hierarchically higher management structure.

Against the backdrop of the dominance of several developed countries in information technology and the emergence of global monopolies that control digital network infrastructure, digital information flows and databases, there is a severe threat of digital colonialization to the countries weak in the digital realm and largely reliant on world tech-giants.

Furthermore, the fact that technology highly permeates every aspect of contemporary human life and exists as a ubiquitous layer tracing every object or event in the physical world adds gravity to the situation. Therefore, digital sovereignty is synonymous with many other sovereignties.

For example, information sovereignty could be defined as the right of a country to independently form information policy (and therefore state administration), manage information flows, ensure information security regardless of external influence. On the other hand, the countries whose own digital infrastructure is weak open wide doors for supranational administration — control and administration performed on their territory over their resources but not in their national interests. This again touches all aspects of citizens’ lives and creates a serious threat to the lives of public administrators themselves!

However, information sovereignty might be of lesser concern to a country that historically did not play a prominent role in the global geopolitical projects. Nevertheless, the danger of becoming some else’s raw material appendage is real for any country rich in natural resources but poor in digital infrastructure. As real is the possibility of falling victim to uncontrolled access to its markets.

The uncontrolled and exploitative access to our economic space is already a day-to-day reality for Malaysia, and it is just the beginning.

For example, the e-commerce platform space is nearly entirely dominated by Shopee (Singapore, Sea Limited) and Lazada (China, Alibaba Group). Malaysians constitute close to 15% and 12% of the active users base for Shopee and Lazada, respectively. Therefore, while Lazada has recorded $1 billion in revenue in 2020 and Shopee’s revenue is expected to reach at least $4.7 billion this year, that makes us lose close to $1 billion to just these two aggregators.

The online travel and lifestyle services segment in Malaysia is led by foreign-owned companies such as Booking.com (Dutch), Traveloka (Indonesia), Agoda (Thailand), while Grab (Singapore) or Foodpanda (Germany) overshadow the e-hailing and food delivery. And the list can go on for the entire technology-infused creation and delivery of lifestyle products and services expected only to grow in their command of consumers’ lives.

Of course, some may argue that the entry of these foreign aggregators and unicorns into our economic space is good as it creates employment and economic activity. Yes, no one can argue that colonization always creates economic activity and “employment”, but unfortunately never to the ultimate benefit of those employed and deployed.

This probably could be a book example of how one strategic manoeuvre can solve the whole vector of goals.

First, the foreign intruders benefit by exploiting our economic space (expanding the economic space for their products and services).

Also, they do not mind onboarding our micro, small and medium entrepreneurs (MSMEs) because they know that our products cannot compete with theirs in the same economic space on price or quality. However, the onboarding of the local MSMEs is another source of revenue for them. And if the local MSMEs see an exploitive 30% cut into their profit prohibitive enough to be onboarded, the aggregators without shame approach our government agencies for grants to subsidize the onboarding. Finally, and most outrageously, our agencies entertain them probably due to widespread corruption, speed-to-spend mentality and general disregard for actual societal outcomes and impacts.

Furthermore, by increasing our complacency and reliance on them, these tech-savvy intruders stall the growth and development of our cyberpower (deconstructing our digital sovereignty).

The scientific publications recently more and more often place the state’s cyberpower or a measure of the ability to enforce one’s will in cyberspace as the primary antecedent of its “digital sovereignty”.

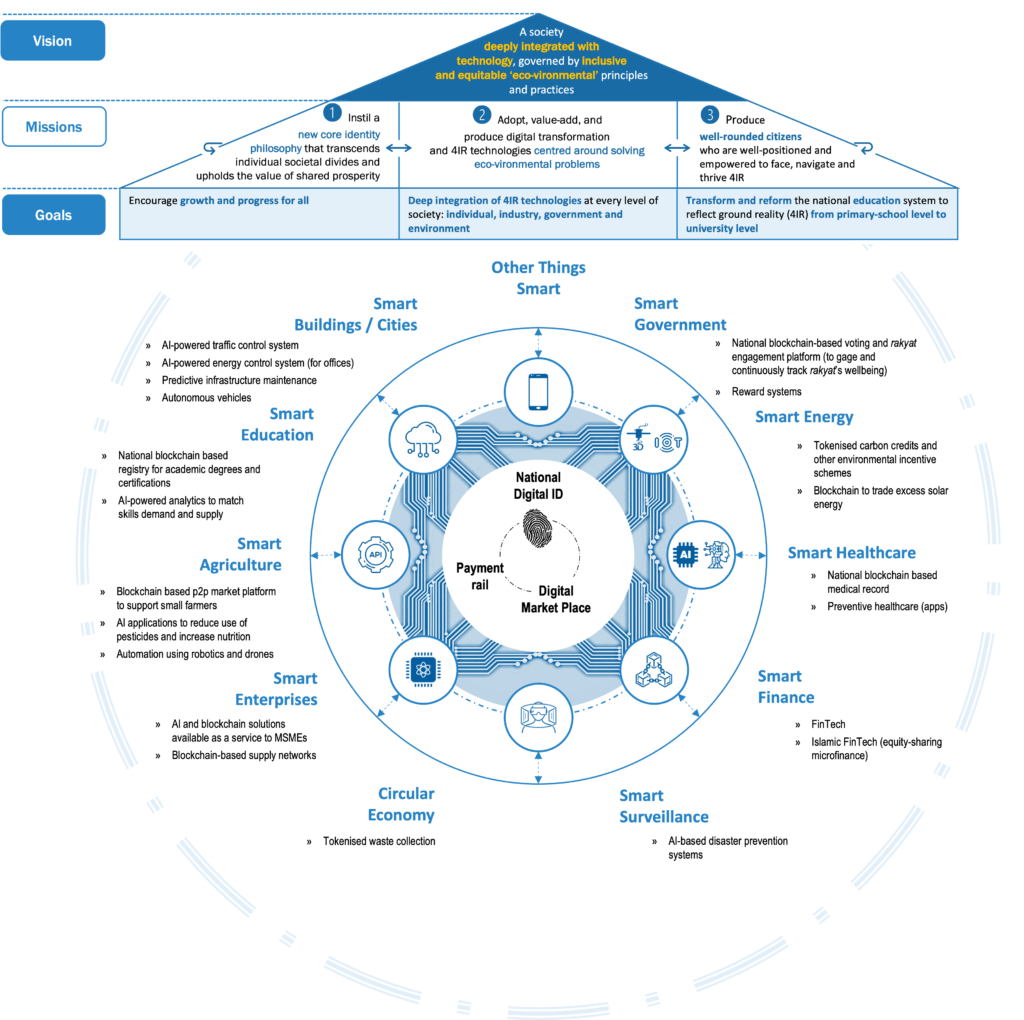

In other words, to stop intruders from juxtaposing their cyberspace on our physical territory and in our economic space only for the purpose of extracting resources, we need to start creating our own rakyat-centred cyberspace, as envisioned under the concept of Malaysia 5.0 (figure below). Only such rakyat-centred cyberspace can empower, liberate, and provide economic growth and prosperity to the entire societal ecosystem leaving no one behind including our natural habitat.

Figure: Malaysia’s owned rakyat-centred technology layer (Source: EMIR Research)

The building blocks for such a cyber-sovereign future are long time known.

As the foundation, we need infrastructure elements essential for the functioning of cyberspace, starting with the dense cable landing, which leads to an abundance of connectivity and bandwidth. The latter only naturally attracts the data centres industry which is crucial and currently is lacking in Malaysia.

Note that Malaysia has just missed the perfect opportunity to fill this void due to resistance to reinstate cabotage exemption that had been previously in place for submarine cable repair vessels. This exemption has nothing to do with defending digital sovereignty but only hurting it at the most fundamental level.

Further, the country needs to ensure a stable supply of well-rounded citizens who are well-positioned and empowered to face, navigate, and thrive 4IR and 5IR (as elaborated by EMIR Research in the article “Building blocks for Malaysia 5.0” from December 1, 2020). Unfortunately, despite the urgent call, there is no evidence of policy attempts to transform our education system until now.

We also do not want to produce these well-rounded citizens and competitive IT manufacturers to be employed in a foreign land. Therefore, it is crucial to ramp up the speed and scale of the country’s innovative potential, scientific progress, ability to carry out and apply research for industry development and transformation. In the new century, emphasis on national production and import substitution in as many areas as possible, especially where high-tech elements are used, is becoming an absolute dominant of the renewed sovereignty. Narrow specialization, the tale of competitive advantage and economies of scale are becoming the relics of colonial past under the equalizing power and efficiency of 4IR. No national market can ever be too small for a well-developed sovereign 4IR.

However, above all, we need adequate national legislation that ensures the achievement of such goals. The government’s sincere desire, seriousness, and integrated capability to create robust strategies for conquering cyberspace are even more fundamental and primary to the factors listed above. A consistent, coherent and clear theory-driven and outcome-impact-oriented policy (cyber strategy) is needed before we become complete digital Kunta Kinte of other nations beyond the point of no return.

Unfortunately, as it currently stands, national policies haphazardly defend digital sovereignty where there is an opportunity to build our cyberpower and close the eyes on actual digital colonization. This is high time to put things in order in our digital space by re-establishing its boundaries and formulating a distinctive and clear strategy towards forming a new component critical for the nation’s survival — “digital” sovereignty.

Rais Hussin and Margarita Peredaryenko are part of the research team at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.