Published by Malaysiakini, images from Malaysiakini.

The recent escalation of tensions between India and Pakistan encouraged Malaysians once again to review their attitude towards regions of the world where people suffer from war and oppression.

Malaysia has taken a decisive pro-Palestinian stance in the Arab-Israeli conflict that traces its origin to the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, but has been less vocal on the India-Pakistan conflict over Kashmir, which originated from the partition of India in 1947.

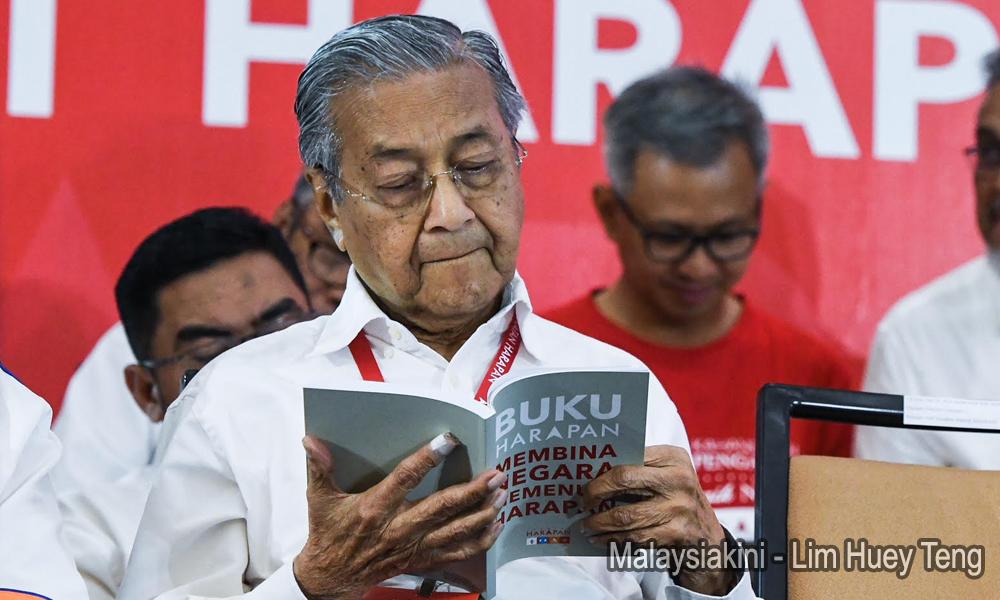

Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s speech in the UN General Assembly on Sept 28, 2018, and the decision to ban Israeli athletes from participating in the 2019 Para Swimming Championships made a clear point about Malaysia still supporting Palestine in the conflict, no matter what reputational and financial losses it entails for Putrajaya.

This was also the fulfillment of Pakatan Harapan’s manifesto promise 59 – to lead the effort to resolve the Rohingya and Palestine crises.

Criticising BN and Umno for not taking any concrete steps to “to ensure voices of our oppressed brothers and sisters are heard”, the manifesto did not specify those steps, except for mentioning the need to ratify the 1951 International Convention on Refugees.

However, when it comes to South Asia, Malaysia appears to be more discreet.

Similar to the case of Yemen, Malaysia is trying to limit its scope to humanitarian matters, especially guaranteeing safety of its citizens in the problematic areas and advising against traveling to those destinations, as well as delivering humanitarian help through NGOs.

Of course, this is not completely similar to the case of Yemen, where Malaysian troops controversially participated in the Saudi-led military campaign against the Yemeni Ansar Allah (commonly known as the Houthi movement).

The previous government expressed its support to the plight of Myanmar Rohingyas only superficially, as it was clear that the statements made by ex-prime minister Najib Abdul Razak and Umno members was mostly in the context of a fight for the hearts of his voter base, rather than an attempt to persuade the military junta or Aung San Suu Kyi to be proactive in resolving the crisis.

The current Harapan government earned its legitimacy on May 9 last year and has been preoccupied with augmenting it since then.

This means it remains concerned with what ordinary Malaysians and Malays in particular think about government’s political initiatives, especially after the Semenyih by-election.

That is why the government’s attention to certain foreign policy moves depends on the domestic demand for it to react.

A coalition of 43 NGOs supported Wisma Putra’s decision regarding the Israeli athletes. The expectation for the current administration to support Palestine in their conflict has been there for a long while.

On March 6, the Malaysian Consultative Council of Muslim Organisations (Mapim) and the Pakistan High Commission co-organised a program to update the public on the situation in embattled Kashmir, parts of which are controlled by India, Pakistan and China.

It might look like a drop in the sea, but Mapim chairperson Mohd Azmi Abdul Hamid reiterated the same thought about how people matter in mapping foreign policy.

“Our government is elected and we want the new government to hear our voice, we are trying to reconnect people with the government,” he said after reading the resolution of the meeting.

Azmi promised that Malaysia’s NGO note of concern on the India-Pakistan crisis endorsed by 17 Muslim organisations will be forwarded to the government of Malaysia, respective governments of India and Pakistan, as well as to Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) and the UN.

Mapim may be unknowingly helping Harapan fulfil another of its manifesto promises – number 60, which is about promoting Malaysia’s role in international institutions.

Even though this looks quite insignificant, this could be the only way to draw the government’s attention to the need to make stronger statements.

Malaysia has been an example of stability; not absolutely, but certainly relative to the rest of Southeast Asia, to its neighbors in South Asia and, further away, to the countries of the West Asia.

It possesses a sufficient international credit to offer its help in mediating – not only for the current escalation that hopefully will be soon over, but to a stagnating, ruthless conflict that injures, abuses, rapes and annihilates the people of Kashmir.

The call is not about ultimately taking Pakistan’s side. Instead, it is about taking more action on promise number 60 – to initiate the right motions in international institutions to force the parties involved to the negotiation table about Kashmir.

Speaking at the recent “Stand with Yemen” forum that was conducted by a number of organizations at the International Institute of Islamic Civilization and Malay World (Istac) on Feb 23, Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah called for the “perpetrators” in the Yemeni conflict to be held accountable, possibly via the International Criminal Court (ICC).

However, he said the Malaysian government would come up with “a good statement” on the matter “after Semenyih”.

If even Wisma Putra ties international issues to matters of limited domestic significance, then it is clear that what the government wants to execute internationally will depend on what the people demand.

In turn, formulation of these demands requires the public to be well-informed on the matter.

Therefore, it is a two-way street to maintain awareness, and to absorb and process information, in order to formulate how the nation sees itself, not only domestically but internationally.

The majority of Pakistan being Muslim, the nature of Malaysian NGOs active on this issue (meaning Mapim) and pre-existing attitudes towards the problem of Kashmir means that public opinion would probably lean towards supporting fellow Muslims against predominantly Hindu India.

Yet, one-and-a half track diplomacy connecting Malaysian NGOs to foreign governments and international institutions can be a good start in seeking justice for Kashmiris.

After all, there no harm in at least trying to play a positive role in regional conflict resolution, while at the same time fulfilling pre-election promises.

Julia Roknifard is Director of Foreign Policy at EMIR Research, an independent think-tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based upon rigorous research.