Published in Astro Awani, Business Today, Asia News Today & theSundaily, image by Astro Awani.

In his inaugural speech as the nation’s 9th Prime Minister, YAB Dato’ Seri Ismail Sabri’s outlined his vision of the private sector in playing the role “as significant drivers of nation’s economic growth” which is integral the long-term strategic objective of the government to drive the national recovery (August 22, 2021).

One of the components in the private sector is foreign direct investment (FDI).

Whilst FDI has long been a mainstay of our economy – there are concerns by some quarters as to whether it can be sustainable or could its decline, if it’s the case, be arrested and reversed.

Although, in terms of investment value, FDI’s contribution to our economy doesn’t seem impressive enough, the multiplier effect can’t be strongly emphasised enough.

In an article, “FDI & Growth: What Causes What?” (The World Economy, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 9-19, January 2006), Abdur Chowdhury & George Mavrotas have suggested that in the case of Malaysia, there seems to be strong evidence of a bidirectional causality between GDP (gross domestic product) and FDI. Meaning that FDI growth impacts on GDP growth as much as vice-versa.

On the other hand, other scholars like Mohammad Sharif Karimi and Zulkornain Yusop have argued in “FDI and Economic Growth in Malaysia” (Munich Personal RePEc Archive, 2009) that there’s no clear empirical correlation in terms of causing mutual growth. This article doesn’t deny that there’s a relationship. The authors noted that the “the performance of one variable does contribute to stability of another variable”.

As it is, the apparent contradiction between the two articles could simply be resolved by referring to the following factual/contextual propositions:

- Our FDI inflows has consistently been around 3% to 4% on average since 1998. During the initial stage of the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC) in 1997, it peaked to 5.1% according to the same data from the World Bank;

- All the while our GDP growth has outstripped FDI growth. This suggests that FDI into Malaysia has stagnated (or “stabilised”).

And Covid-19 has, of course, adversely impacted on our FDI with border restrictions and lockdowns.

This means that one of the critical tasks facing the new administration is to revive and increase FDI inflows – to ensure its sustainability in supporting our economic growth, transition and move to the next stage of development.

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (Unctad)’s World Investment Report 2021, Malaysia lost out on FDI at a worse rate than neighbouring Southeast Asian countries and the rest of the world. Malaysia’s FDI was down 55% and amounted to just USD3 billion (RM12.4 billion) compared to the wider Asean region which lost 25% (declining to USD136 billion or RM 564 billion).

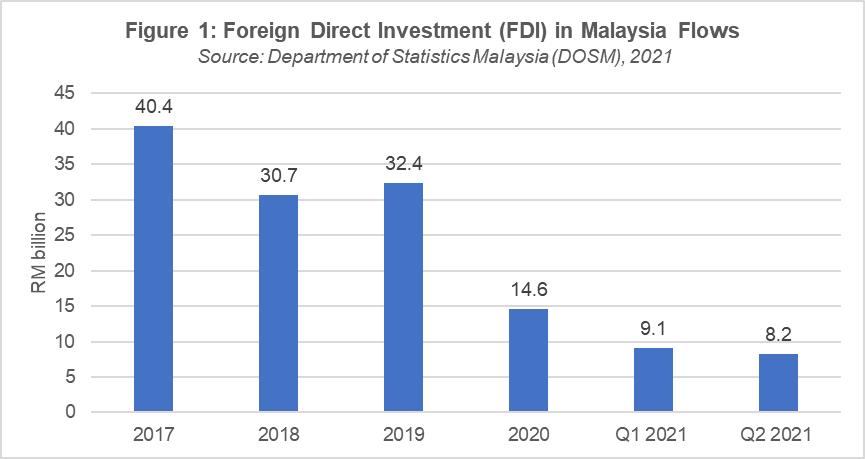

The Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM)’s Quarterly Balance of Payments revealed that Malaysia saw a steep decline in FDI in 2018 compared to the preceding year. Our FDI more or less stagnated (or “stabilised”) in 2019 – i.e., from RM30.7 (in 2018) billion to only RM32.4 billion.

And due to the impact of Covid-19, our FDI for 2020 plunged to RM14.6 billion.

Lately, we registered a net inflow of RM8.2 billion in Q2 2021, compared to RM9.1 billion in Q1 2021.

For Q2 2021, the inflow of FDI was mainly from Japan (RM2.1 billion), followed by Indonesia (RM1.5 billion) and the United States (RM1.4 billion).

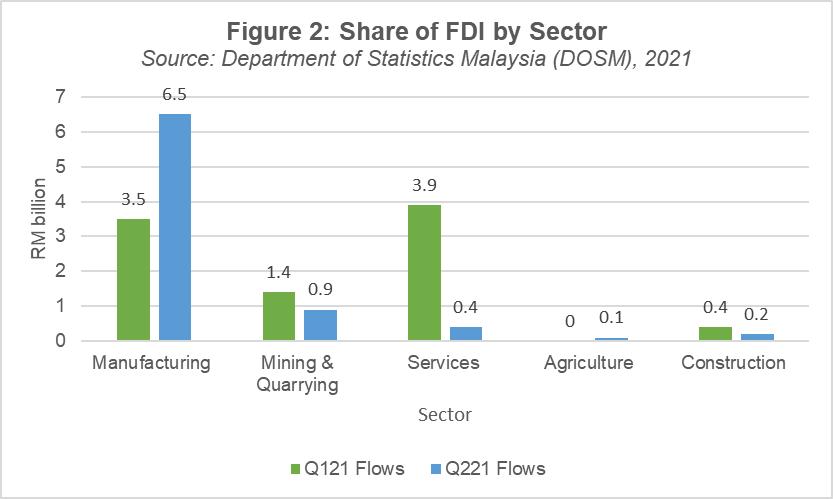

In terms of sector, FDI inflow in Malaysia was mainly channelled into the manufacturing sector which accounted for RM6.5 billion or 79.9% of the total flow in Q2 2021, an increase from RM3.5 billion in the preceding quarter.

This was followed by mining & quarrying and the services sectors which registered RM0.9 billion and RM0.4 billion in Q2 2021, respectively, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Although Operation Surge Capacity in the Klang Valley marked a great success, the steady vaccination progress has not helped to counter the adverse impacts from the prolonged lockdown.

Furthermore, the continuous spike of Covid-19 cases in other Malaysian states has led Fitch Solutions to revise Malaysia’s 2021 GDP growth to 0% from its earlier estimate of 4.9%.

The research outfit also revised private consumption growth to a contraction of 2% from 3% growth previously while forecasting gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) to grow at mere 1.5% from 4% previously.

Moreover, the revocation of the cabotage exemption policy for submarine cable repair in November 2020 eventually resulted in Facebook and Google to bypass Malaysia in Asia Pacific. And now Facebook and Google have announced that Apricot – a new 12000 km subsea cable – will connect Japan, Taiwan, Guam, the Philippines, Indonesia and Singapore to further boost connectivity in Asia Pacific.

The Malaysian Reserve in a news report “Subsea cable exclusion a loss to digital Malaysia’s future” (August 30) has highlighted MIDF Research house’s estimates of “Malaysia’s exclusion from the Facebook and Google-backed Apricot subsea cable will result in a loss of high-capacity connectivity and investment worth USD300 million-USD400 million (RM1.26 billon-RM1.68 billion)”. The revocation of the cabotage exemption policy has also put some RM12 billion to RM15 billion worth of digital investment at risk.

EMIR Research would like to propose some policy recommendations in support of the new administration’s effort to maintain and enhance Malaysia’s position as a premier FDI destination:

- Based on the figures/graphs provided above (among others) there’s a need for us to increase the quantum of FDI value. Towards this end, we need to ensure that FDI flows not only into the downstream of manufacturing activities (as the primary sector) but also the mid- and upstreams.

The government could provide tax/fiscal incentives for joint-ventures (JVs) to be formed between multinational companies (MNCs) and our small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and mid-tier companies (MTCs) and not least our government-linked companies (GLCs) – for localising and regionalising the supply chain.

Another incentive is to encourage FDI into regions outside of the Klang Valley, Penang and Iskandar Malaysia by introducing a regional maximum demand (MD) charge for the industry tariffs (“Decentralising development and utility cost key to rejuvenating the economy”, Sharan Raj, Focus Malaysia, July 27). Currently, electricity demand is over-concentrated in the central region. A MD means that electricity tariff in East Malaysia, for example, should be the lowest.

East Malaysia is well-poised to receive FDIs in green and renewable energy with e.g., the establishment of the Sarawak Corridor of Renewable Energy (Score).

As such, we should also expand our scope of FDI to focus also on the green economy. This includes FDI in ecotourism infrastructure of which Sabah has great potential as a premier hub.

- Develop targeted incentives to attract high-tech FDI that will integrate the domestic supply chain, promote spillover in terms of technology transfer and developing a new breed of entrepreneurs and technopreneurs, including in the critical areas of food security and smart farming as well as electric vehicles (EVs), etc.

This should be part of the National Investment Council’s strategy to attract quality FDIs through the Ministry of International Trade & Industry (MITI) and under the National Investment Aspirations (NIA) framework. Incentives could include government co-investment matching grants, double tax deductions, supplementary avoidance of double taxation agreements, exemption from import duties for capital goods and equipment, export subsidies/credits, etc;

- Restoration of the cabotage exemption and have the legislation (Merchant Shipping Ordinance 1952) amended to remove submarine cable activities from our definition of cabotage for the sake of attracting more investments, especially the higher value digital investments; and

- Malaysia should revive bilateral free trade talks with partners such as the EU which stalled since 2017.

Michalis Rokas, the EU Ambassador to Malaysia, have insisted that “[t]he palm oil issue is not a stumbling block for FTA negotiations to recommence”, noting that the EU and Indonesia are currently engaged in free trade agreements (FTA) negotiations, although facing the same situation concerning palm oil.

And in April, the European Chamber of Commerce in Malaysia (Eurocham) and the Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers (FMM) agreed to form a joint task force to lobby the government for a restart to FTA talks.

In summary, we need to expand on the scope of our FDI (which we have already done so in the pre-existing sectors such as aerospace and more recently in the form of strategic investment sites, i.e., KLIA Aeropolis, and Subang Airport Regeneration Initiative) – thus moving beyond traditional categories as well as prioritise on bilateral FTAs (before we seek to decisively ratify the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership/CPTPP where caution, and not outright rejection per se, is urged).

Jason Loh and Amanda Yeo are part of the research team of EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.