Published by BusinessToday, malaymail, malay.news, AstroAwani, malaysiakini & Malaysian Must Know the TRUTH, image by BusinessToday.

The perplexing phenomenon widely recognised as “brain drain” has burgeoned into an all-encompassing challenge globally, especially prevalent within lower and middle-income countries.

Malaysia, in particular, is grappling with a notable “brain drain” exodus of highly skilled professionals, especially within the healthcare sector, raising concerns about the repercussions on the nation’s healthcare system.

If this migration continues to persist, the healthcare system will confront a growing void marked by critical manpower shortages, compromised patient care, and strained resources, as Malaysia is already experiencing an ageing population.

According to EMIR Research findings previously, Malaysia has been experiencing an exponential brain drain over the past four decades (see “Malaysian brain drain – don’t go chasing waterfalls, EMIR Research, 2022).

Consistent with EMIR Research estimates, a year ago, the then Human Resource Minister, V. Sivakumar disclosed that 1.86 million Malaysians live abroad, with 1.13 million of them residing in Singapore.

In addition, local media has extensively reported that Malaysia has experienced a brain drain rate of 5.5%, significantly surpassing the global average of 3.3%.

Malaysia’s experience with global talent migration, surpassing global averages, creates a scenario that demands urgent attention and comprehensive analysis.

In the context of the healthcare industry, the World Bank report indicates that Malaysia has been experiencing an annual loss of approximately 20% of its trained medical professionals since the late 1990s.

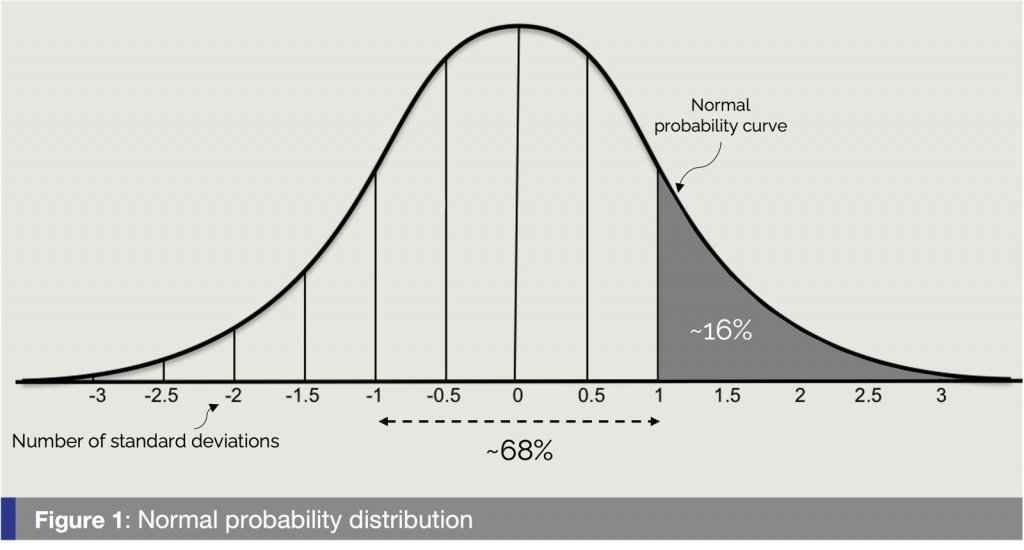

To grasp the gravity of this statistic, EMIR Research highlights the well-established Gaussian normal distribution (Figure 1) of human intelligence in the population. With 68% in the middle possessing average knowledge, skills and abilities, and 16% on the right-hand tail exhibiting extremely high potential, losing 20% suggests Malaysia might be losing a substantial portion of its top healthcare workforce.

It is crucial to determine whether these numbers suffice to meet national healthcare demands because, as widely discussed, our Medical Officer (MO) diaspora has already dispersed widely, particularly to countries like Singapore, New Zealand, Australia, the United Kingdom (UK) and the Middle East, attracted by rewarding remuneration, better career prospects and a higher quality of life.

For instance, in 2021, 2,581 Malaysian doctors and nurses served in the UK’s National Health System. By June 2023, this number increased to 3,123 (21% surge), as reported by the United Kingdom National Health Service (NHS). If left unaddressed, this escalating trend presents a serious risk to Malaysia’s healthcare system.

A cross-sectional study among 316 specialists working under the ministry conducted by Daud et al. (2022) revealed profound dissatisfaction with various aspects, including operating conditions, fringe benefits, promotion, pay, and contingent rewards. The overall job satisfaction rate was only 30.7%.

This signals a serious discontent among MOs with the healthcare system, highlighting the need for a thorough investigation into the root causes of frequent brain drain within Malaysian healthcare. This is in addition to the widely acknowledged issue with “contract doctors.”

The Intersection of Poor Mental Health and quality of life of MOs

The demanding nature of healthcare professions, marked by high workload, emotional toll, burnout, on-call duties, sleep deprivation and unpredictable working hours, remains a persistent challenge. Naturally, these are expected to intensify with the growing brain drain.

While the spotlight often shines on physical health concerns, the MO’s mental health struggles remain overlooked and underreported.

Dutheil et al. (2019) indicate that MO is an at-risk profession for suicide, with women particularly at risk. Additionally, Grover et al. (2018) found that 90% of 1607 MO participants in North India had some degree of burnout, with 67.2% reporting moderate stress and 13% extreme stress.

In Malaysia, Shahruddin et al. (2016) found that 57% of 121 surveyed houseman in an East Malaysian training hospital reported stress while anxiety and depression had prevalence rates of 63.7% and 12.9%, respectively.

This suggests a lack of protection for the physical or mental well-being of our healthcare professionals.

This pattern is especially concerning because doctors experiencing psychological distress may struggle to provide optimal patient care. Junior doctors, in the early stages of their careers, are particularly vulnerable due to extended working hours and insufficient sleep. While the challenging environment can serve as a training ground, it also adversely affects their physical and mental well-being.

Compensation disparities

The substantial wage gap with other countries, along with prolonged working hours, significantly contributes to the prevalent brain drain among healthcare professionals in Malaysia.

For instance, doctors undergoing training in the UK can earn approximately £2,333 monthly (RM 13,830), while our fresh graduate doctors average only RM3,500, including allowances. Additionally, on-call work compensation is a meagre RM200 for 28 hours, disproportionately low for a doctor.

Furthermore, educational debt significantly contributes to brain drain among fresh graduates and junior doctors. Those burdened with substantial student loans are lured by the prospect of superior financial rewards abroad. Consequently, regardless of whether they attend government or private institutions, they are more inclined to migrate to neighbouring countries.

This stark disparity, coupled with issues like limited career advancement and social injustices, particularly affecting certain ethnicities, emerges as a potent catalyst for the brain drain in Malaysian healthcare.

Poor human resource management (HRM)

Ineffective HRM practices in healthcare, including the maldistribution and misassignment of professionals, contribute to dissatisfaction and an overall drive to seek opportunities elsewhere. This is exemplified by situations where healthcare professionals may find themselves understaffed, underpaid, and burdened with excessive workloads. Top of FormHRM serves as the backbone for a successful, streamlined, and high-quality healthcare industry. The following foundational HRM elements are crucial for the overall proper functioning of the healthcare sector:

- Implementation of a lawful and ethical managerial framework

- Analysis and design of job roles

- Hiring and selection processes

- Opportunities in healthcare careers

- Administration of employee benefits

- Motivation of employees

- Dialogues with organised labour

- Employee terminations

- Identification of evolving and future trends in healthcare

- Strategic planning

However, it is evident that Malaysia currently lags in both managerial and operational aspects of healthcare HRM, with loopholes in most of the listed elements, leading many medical professionals to seek fulfilling experiences abroad.

The departure of healthcare professionals creates imbalanced patient-doctor and patient-nurse ratios in Malaysia. Presently, the ratios are as follows: doctor-patient ratio of (1: 412), nurse-patient ratio of (1:279), and pharmacist-patient ratio of (1: 1,653).

In contrast, Singapore exhibits a more favourable scenario compared to Malaysia. Singapore boasts a doctor-patient ratio of (1:354), nurse/midwives-patient ratio of (1:129), and pharmacist-patient ratio of (1:1,446).

Interestingly, it’s worth noting that Malaysia experiences a significant brain drain, with at least 30% of its medical graduates from the University Malaya (UM) opting to pursue opportunities in Singapore, as highlighted by Datuk Dr. Adeeba Kamarulzaman, the former dean of the university. Remember the normal distribution of human intelligence again (Figure 1)!

Increased professional migration intensifies strain on the remaining healthcare workforce, potentially causing longer waiting times, reduced care quality, etc.

Following are the proposed policy recommendations by EMIR Research to relevant stakeholders, to tackle challenges arising from the healthcare brain drain crisis:

- Emphasising Mental Health Support for Healthcare Workers: Establishing mental health support programs, counselling services, and resources is crucial. Prioritising the mental health and well-being of healthcare professionals can significantly alleviate stress and burnout, ultimately increasing the likelihood of retaining them in their current positions.

- Customised Career Advancement Initiatives for Medical Officers (MOs): The implementation of clear career progression paths and opportunities for specialisation is essential for Mos. When healthcare professionals perceive a well-defined route for career growth within their home country, they are more inclined to stay committed to their roles.

- Merit-Based Career Development Framework: It is imperative to establish standardised and achievable Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for MOs to attain. This approach ensures a fair and transparent merit-based system for career development, establishing fair workload practices, promoting professional growth and job satisfaction.

- Equitable Distribution of Employee Benefits: Both permanent and contract doctors should receive compensation based on their workload and work contributions to uphold equity and fairness.

- Integration of 4IR/5IR Tools in Healthcare Practices: Embracing Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) and Fifth Industrial Revolution (5IR) technologies is essential for healthcare effectiveness and efficiency. For instance, the integration of telemedicine, AI-assisted diagnostics, and digital health records can streamline healthcare processes and elevate the overall standard of patient care.

- International Collaboration and Exchange Initiatives: Facilitating international collaboration and exchange programs for healthcare professionals is pivotal. Such programs will provide opportunities for skill transfer and knowledge enhancement but also foster a global connection. For these purposes, the government can also leverage the existing Malaysian healthcare diaspora as one of the working strategies (refer to “Credible Malaysian Brain Drain Intervention is Long Overdue!”).

Essentially, our medical field is in crisis — that of undervaluing its workforce.

Urgent and decisive action from key stakeholders is direly needed to combat the looming threat of healthcare brain drain that, apart from other expected negative impacts on Malaysians, also hinders our progress toward high-income and developed status, as talents are lost to neighbouring nations. The need for impactful intervention is indeed pressing for the current administration.

Jachintha Joyce is a Research Assistant at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.