Published in BusinessToday, image by BusinessToday.

Malaysia’s 5G rollout saga continues with surprising twists—worthy of a television drama. However, these unexpected developments are likely less appreciated by local industry, stakeholders, and the public, as shown by the strong backlash following the latest Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) announcements.

While establishing a nationwide Single Wholesale Network (SWN)—a model widely seen as ineffective and detrimental globally—could perhaps still be camouflaged to some extent, the latest development in Malaysia’s 5G rollout is undeniably difficult to justify.

In a statement on 1 November 2024, the industry regulator informed that U Mobile Sdn. Bhd. Was selected to implement Malaysia’s second 5G network, allowing it to ‘collaborate’ with other mobile network operators (MNOs). MCMC will oversee the implementation to ensure compliance with the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998.

The rationale behind this decision is so opaque it overshadows even the lack of transparency in the tender process. True transparency, notably, requires that selection criteria be made public before the process begins.

The MCMC’s so-called ‘explanation,’ combined with U Mobile’s response, not only adds no clarity but heightens the confusion. Malaysia’s 5G rollout appears destined to remain shrouded in unanswerable questions with self-evident answers, as it has from the start.

Interestingly, none of the criteria revealed by the MCMC are of a substantial or technical nature—everything ‘can be enforced,’ ‘can be monitored,’ or ‘can be adjusted’—clearly suggesting a retrofitting approach or a ‘selection’ process without real selection. This underscores the need for a thorough, prudent inquiry into the full list of criteria and complete documentation of the selection process.

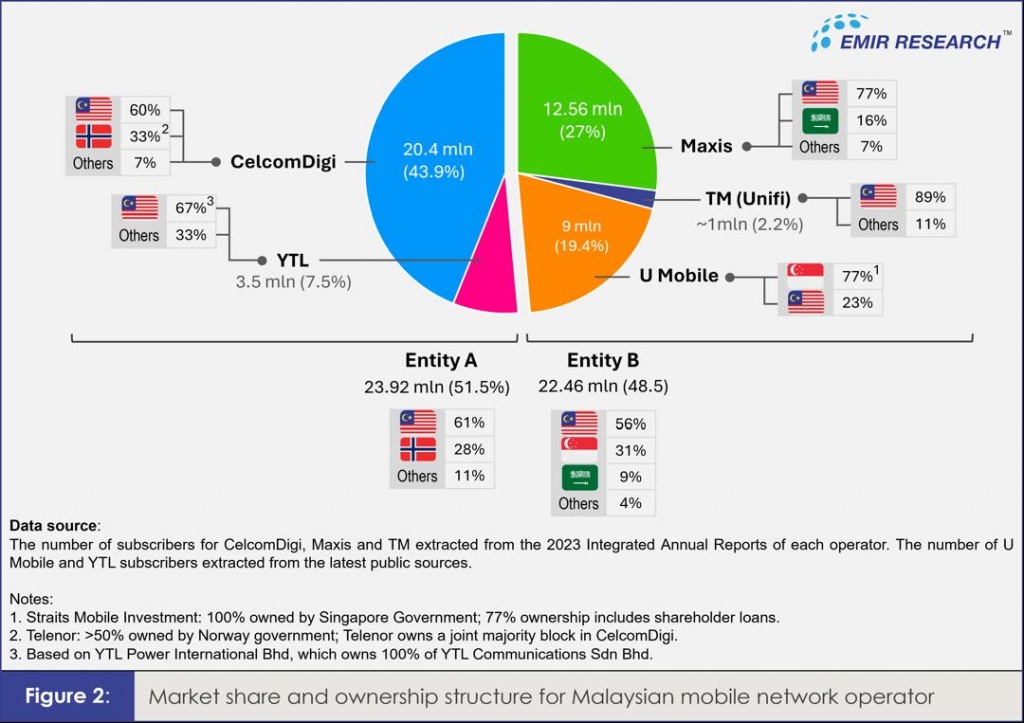

Even a layperson might question why U Mobile—a smaller player with about 19.4% market share and 9,000 plus sites—was chosen to build the second national 5G network over MNOs with scale, resources, in-house expertise and partner ecosystems such a project clearly demands.

EMIR Research (ER) previously highlighted that Malaysia’s slightly higher than 80% Coverage of Populated Area (COPA) is essentially meaningless, as serious weaknesses in the 5G Connectivity Index (5GI) are evident in nearly every dimension, particularly the severe insufficiency of 5G towers, which points to potentially overstated COPA.

While customers may not yet feel the impact due to a relatively low subscription base, this will change as subscriptions grow. Without significant expansion in cell site density, Malaysian customers risk receiving 4G-level service at a higher 5G price, contrary to original SWN promises, as we now know.

ER has stressed the dire need to re-think the efficient use of existing resources, particularly 48,000 jointly owned cell sites by major MNOs, which are largely 5G-enabled, to swiftly address these issues.

Clearly, there are causes for concern.

This concern deepens with recent developments from the Malaysian regulator. It remains unclear how awarding the right to implement a second 5G network to a smaller player like U-Mobile—with a number of cell sites not far exceeding DNB’s—will effectively address the situation. Could we now end up with two competing 5G networks, both with insufficient 5G COPA?

Furthermore, no details have been provided on spectrum allocation or the specifics of the permitted cooperation framework between U Mobile and other MNOs. Does this arrangement imply a “renting” model again, potentially limiting meaningful input in a domain as socially significant as spectrum allocation? Also, how does this align with the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998?

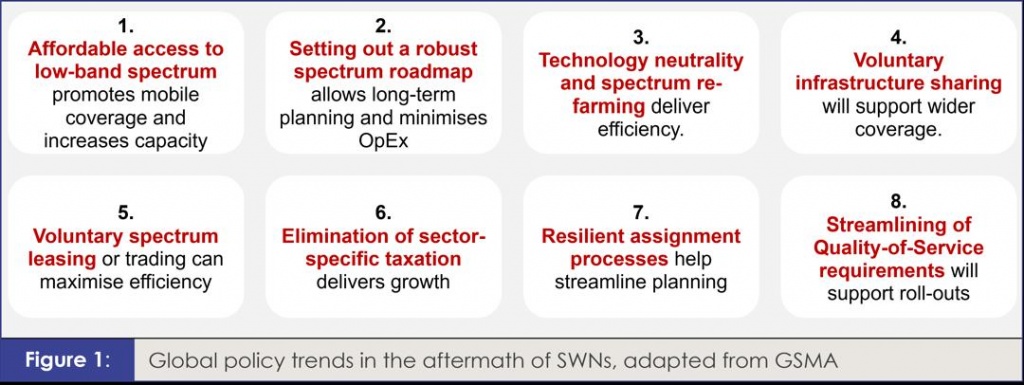

It is disappointing that Malaysian public policy has not yet made a radical shift from traditional rent-seeking behaviours, illustrated in “Malaysian 5G Rollout: Spectrum Economics & Deadweight Loss”. This is particularly troubling given years of global observations and empirical research on telecom markets, which highlight essential trends for unlocking the full potential of next-generation networks, especially 5G. These trends emphasise the importance of sufficient spectrum allocation alongside reduced costs and mitigated risks (see Figure 1, also refer to GSMA policy position documents on the issue).

Among other factors, Malaysia’s limited 5G user base, as shown in the 5GI and the resulting lighter network load, not only diminishes the relevance of Malaysia’s widely cited high rankings in the Speedtest Intelligence Test but raises questions about the 5G user base as a meaningful selection criterion at this stage. Additionally, MNOs have yet to control network quality—or much of pricing—while subscribed to the SWN. So, does their 5G subscription base truly reflect anything substantial?

Meanwhile, market concentration should be the most relevant criterion in the MCMC’s decision, especially if the goal is to enhance competition. This is where the situation becomes particularly perplexing.

Since MNOs cannot hold stakes in both competing network entities, if U-Mobile (holding 19% market share) has already expressed readiness to work with CelcomDigi (43.9%) and TM (2.2%), only Yes (7.5%) and Maxis (27%) remain as potential shareholders of DNB. It doesn’t take complex maths to see that this arrangement poses a serious market concentration issue. After all, with two entities, the optimal Herfindahl-Hirschman Index is only achieved if both entities are of roughly equal size. How wasn’t this included as part of the criteria? Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 appears to live only on paper.

Equally perplexing is the priority given to a majority foreign-owned company (with over 70 percent ownership, including shareholder loans), potentially at the expense of predominantly Malaysian-owned MNOs. While allowing foreign-majority-owned entities in critical infrastructure projects can be justified in the name of fair competition, it should not undermine support for home-grown companies, especially in telecommunications—a sector crucial for national security and economic sovereignty.

Prioritising foreign-owned firms risks capital outflows, with profits repatriated rather than reinvested locally, ultimately impacting domestic growth and the ringgit’s value. Additionally, what of the significant investments by Government-Linked Investment Companies (GLICs)—including the Employees Provident Fund, Kumpulan Wang Persaraan, and Permodalan Nasional Berhad—in stocks like Axiata, CelcomDigi, and Maxis?

Rebalancing foreign ownership could involve making U Mobile a fair partner with other MNOs, with market concentration in mind. If U Mobile is announcing ownership changes solely to comply, doesn’t this further reaffirm that its position could become superior (and potentially rent-seeking) compared to other ‘cooperating’ MNOs?

Given all this, it’s unsurprising that the November 1, 2024 announcement has sparked renewed debate and public backlash.

However, it is crucial to reiterate that discussions on the recent MCMC decision should not be conflated with repeated arguments defending SWN or misleading claims about the second network’s impact on taxpayers, which repeatedly resurface again and again. In a recent article, ER provided comprehensive evidence showing how this narrative is misleading (see “Gegenpressing Stalled Pathway: The Urgency of Malaysia’s 5G Transition”). SWN now is water under the bridge. The real issue lies in policymakers’ apparent inability—or unwillingness—to restore genuine competition. There, apparently, the forest does not thin out.

With all the unnecessary derailment from a credible, globally aligned 5G rollout—and confusion introduced by the SWN decision—the need for a swift course correction is clear and straightforward.

The government should immediately divest its stake in DNB to eliminate public funding involvement. Mobile internet quality is best supported by infrastructure-driven MNO competition and robust regulation.

The 200 MHz spectrum block held by DNB should be reassigned promptly to enable multiple networks, as no MNO needs over 100 MHz for 5G. Globally, most operators successfully use 100 MHz or less in mid-band C-band spectrum by employing efficient utilisation strategies.

In line with global trends (Figure 1), spectrum neutrality should be reinstated immediately to maximise benefits for the rakyat. This crucial policy change allow MNOs to begin offering 5G services with significantly greater cost efficiency.

In a scenario A, if a private entity acquires DNB for wholesale-only operations, it should not be an MNO, per the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998. MNOs should then develop their networks with the reassigned spectrum, in line with the global best practices (Figure 1).

Though scenario A is highly unlikely due to DNB’s liabilities, MNOs have shown readiness to take on these responsibilities, efficiently restructure DNB’s assets, and expedite 5G expansion and meaningful densification, leveraging their extensive, 5G-ready base stations.

For fair competition and national security, MNOs should be split into two entities with balanced market shares and a mix of local and foreign ownership (Figure 2).

The straightforwardness, efficiency and strong rationale of this approach is so obvious, making the recent MCMC decision all the more startling.

After five years, why is it still so difficult to simply do what’s right for the industry and ultimately the rakyat, based on data, science and economics?!

The market and international investors may also question why Malaysia is struggling with what Rwanda has achieved (“Malaysia’s 5G dreams: Lessons from Rwanda”).

Undeniably, the rationale behind the Malaysian regulator’s recent decision would still benefit from further clarification, perhaps by having a confirmation process to be conducted by the parliamentary select committee to ensure broader understanding.

Dr Rais Hussin is the Founder of EMIR Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.