Published in Astro Awani, Malay Mail, Malaysiakini, Sinardaily, The Star & MYsinchew, image by Astro Awani.

EMIR Research would like to put forward the fundamental and critical questions that policy-makers (if they are really neutral) should be pressing Digital Nasional Berhad (DNB) to answer instead of FAQ-like questions that serve only to reinforce the main narrative that does not stand to objective scrutiny.

Does the “supply-driven” model really make sense for 5G in the first place?

The biggest DNB problem is in its simplistic thinking by analogy that 5G is already a universal “utility” in our country like electricity or water, and by just “supplying” it, it will be readily and universally taken. Forcing the mobile network operators (MNOs) to take on capacities would do very little when they cannot find the demand to fulfil those, especially in rural areas. Experts agree that the 5G rollout must follow the country’s ability to monetise it, or, in other words, is intrinsically demand-driven!

If DNB still strongly feels that Malaysia is an exception to this rule, they should substantiate their speculation with solid demand estimates with real figures. Where is the technical needs analysis for 5G in the rural areas? How many citizens or business entities can readily take on 5G as it becomes available? In which areas? And how does this stand vis-à-vis cost and pricing? These are crucial inputs to claim the efficiency of the “supply-driven” 5G rollout. Why have we not seen any?

Meanwhile, Malaysia’s general complete unpreparedness for 4IR at a large scale apparent from various world rankings over the last years (see EMIR Research article “Malaysian 5G Rollout — Exhibit “A” for Misplaced Solution” dated February 8, 2022) strongly indicates that 5G can grow organically in our country, or, in other words, there is no rush to push it through supply.

There is another strong argument, due to specifics of the technological sector, in favour of demand-driven gradual or organic rollout of new generation networks by multiple players rather than one. In the IT world (telecom is not an exception), costs come down over time very quickly due to rapid innovation. Therefore, it is crucial to have many players working simultaneously on the research and development of active network equipment as they gradually roll out the network. Being locked with one supplier of such equipment reduces the potential for competitive and dynamic cost reduction over time.

Therefore, DNB’s purported cost benefits might be easily overestimated and hugely overrated due to various other adverse impacts on the telecom industry as a whole and consumers, which DNB have not addressed.

Can the DNB model truly solve the national digital divide? Are there better alternatives to be explored?

MNOs are blamed for wanting to “sweat” their 4G investment and have little incentive to speedily roll out 5G (including rural areas) as per the government’s timetable.

The digital divide is not merely a 5G issue per se, but the lack of basic network infrastructure! And DNB’s proposition does not solve it!

Under DNB, the MNOs are still “expected” or “compelled” to invest upfront in rural or “outer” areas for the new passive infrastructure, i.e., the towers and satellite dishes. Whilst fiber connectivity can easily be covered by the USP, the towers and satellite dishes or the RAN pertaining to the backhaul in support of the last mile delivery will still have to be borne by the MNOs by default. This is because Ericsson is only limited to being the network equipment provider (NEP) in the form of 5G New Radio (5GNR) or active infrastructure and hence the MOCN.

Should the MNOs refuse to expand their passive infrastructure for rural coverage, they risk being left out in the process. That is, there might be a possibility of DNB appointing Ericsson to also provide the passive infrastructure for rural coverage.

In which case, will the costs then be passed (back) to future spectrum allocation or in the form of higher leases?

Thus, in the absence of any regulatory force, the MNOs are caught in a bind (“by hook or by crook”) to overpay either in terms of investment in passive infrastructure in loss-making areas or future spectrum.

How would 5G rollout in rural areas be executed in the first place when the passive infrastructure is weak or sparse?

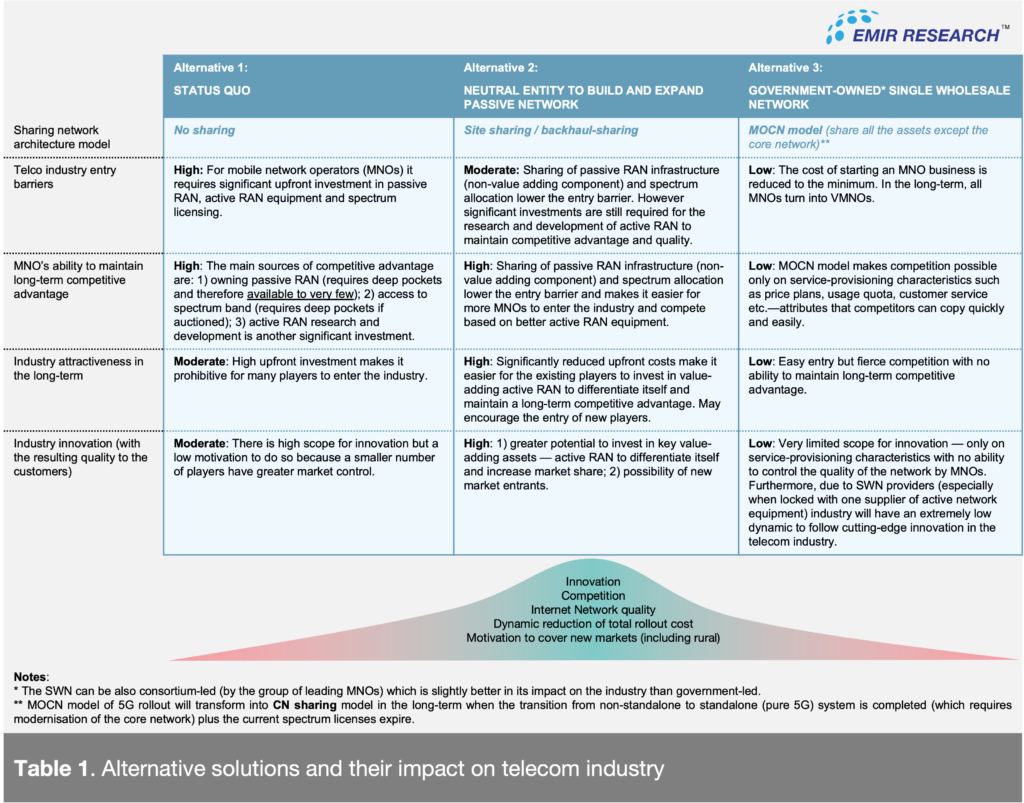

In previous articles on the topic, EMIR Research reiterated numerous times that the solution to the digital divide is for the government to focus on backhaul fibre and towers/poles only – passive infrastructure to be shared by all the telecom players (see Table 1 for alternatives comparison).

In Table 1, Alternative 2 is that direly needed middle-ground solution that sufficiently disrupts the telecom industry’s “status quo” to unlock the desired effects such as internet network quality and a more even coverage, without the heavy expense of adversely affecting the telecom industry development as a whole. A healthy telecom industry ecosystem is one of the key pillars of the fourth industrial revolution (4IR) and beyond. The real danger of making the wrong decision now is not in potentially losing billions of Malaysian Ringgit but a destroyed ecosystem with long-term consequences.

Furthermore, if the government objective is to expand connectivity into rural areas as fast as possible, then the logical question arises: is it not faster to use strategy under Alternative 2 (Table 1) with the 4G first—the technology that is already well-known and costs of deployment could be significantly lower?

Being overly-obsessed with the urgency to push 5G into rural areas, can DNB pinpoint anywhere from the National 5G Task Force Report that 5G would be critical for rural coverage?

How does, for example, entertainment and edge computing etc., based on enhanced mobile broadband (eMBB), massive machine-type communications (mMTC) and ultra-reliable low latency communications (URLLC) feature for rural users? Granted that Internet of Things and, by inclusion, edge computing in supplementing Narrowband IoT for smart or digital farming/agriculture is critical, but this can still be perfectly run on 4G LTE lines which are, in fact, more suitable given the wide coverage area of the farm. In contrast, 5G is high frequency (millimetre waves), but low-band travels very short distances.

As for 5G and the spectrum sharing, this is another matter that should be carefully considered. On one side, spectrum sharing helps overcome the limited availability of bands suitable for 5G and boosts resulting maximum internet speed. However, on the other hand, an important drawback to spectrum sharing is its inimical impact on the industry, as illustrated in the table above. Therefore, the solution requires a wise compromise.

One option for an MNO is to have a full spectrum in designated areas and domestic roaming should be allowed. If the MNO is not performing in the designated area, it should be penalised. There should be wholesale pricing between all the MNOs and the areas can be selected through bidding. As a compromise, there could be two or three MNOs per area to promote competition, but the spectrum divided by two or three is better than dividing by five or eight.

Perhaps this was not clear enough in our previous publications. Therefore, here is the specific question: Why were these alternatives not explored?

Why is the SWN model (government-led or consortium-led) the sole focus while there are better ways to achieve the desired impacts? And if other alternatives were explored, where is the comparative scenario analysis and regulatory impact analysis covering at least two dimensions — effects on market/industry and cost/benefit associated with an entity endowed with special rights and powers such as DNB — for the selection of SWN?

Cost claims must be provided with a detailed breakdown of these costs, verified by experts from DNB, MNOs, and independent bodies, while independent technical experts must verify quality claims. Given that thorough quantitative and qualitative assessments of all potential scenarios under the SWN model have been carried out, have the cost and technical claims by DNB been verified by MNOs and independent experts?

The report by Ernst & Young titled “Estimating the economic impact of the Single Wholesale 5G Network in Malaysia” appears to be based on the potential positive impacts of 5G, solely on the assumption that the SWN model is successful.

Also, there must be independent monitoring (financial, technical etc.) and oversight, given that project costs include sums (reportedly an estimated RM 1 billion) allocated for MCMC (the body regulating DNB) and Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB).

TNB’s biggest shareholder is Khazanah Nasional Berhad owned by the Ministry of Finance Incorporated while DNB is also wholly owned by the Ministry of Finance. How will this ecosystem ensure proper good governance and integrity are in place? What are the mechanisms of checks and balances, oversight, and monitoring on DNB’s key performance indicators (KPIs), financial, legal, and technical matters? The appointment of the Board of Directors does little (if nothing) as far independent external oversight goes.

Is the success of SWN supported empirically or even anecdotally?

To quote DNB Chief Executive Officer’s response, “the case for an SWN is very strong”.

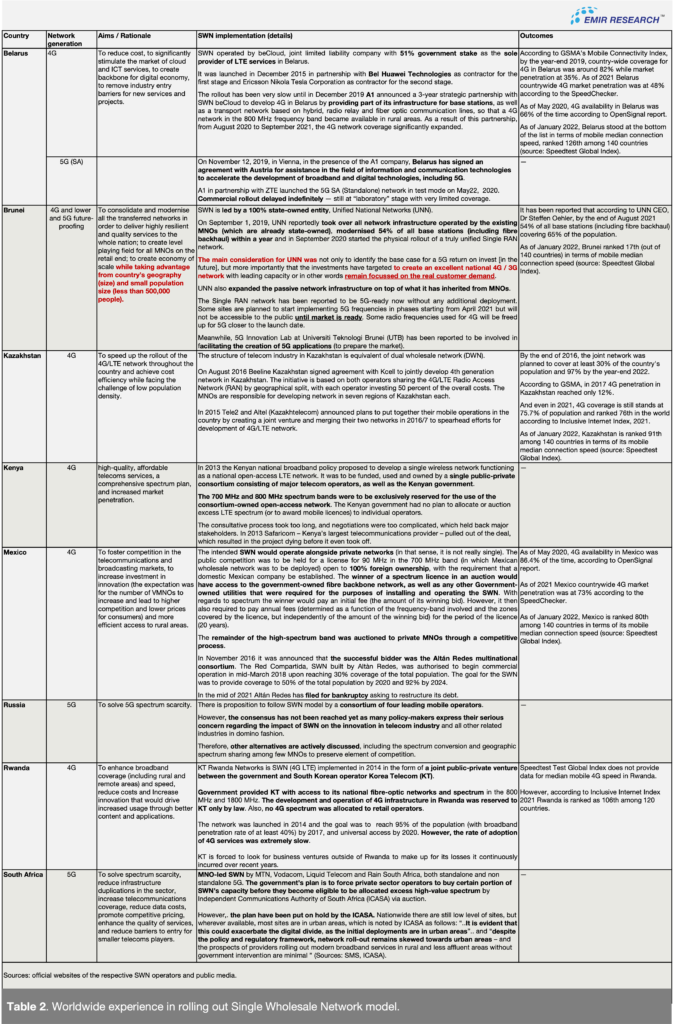

It is so strong that it was never even considered by those 70 nations that champion 5G worldwide. However, are there successful SWN implementations? Are those failed attempts fundamentally different from what DNB suggests? We summarise SWN cases in Table 2 (link to large size here).

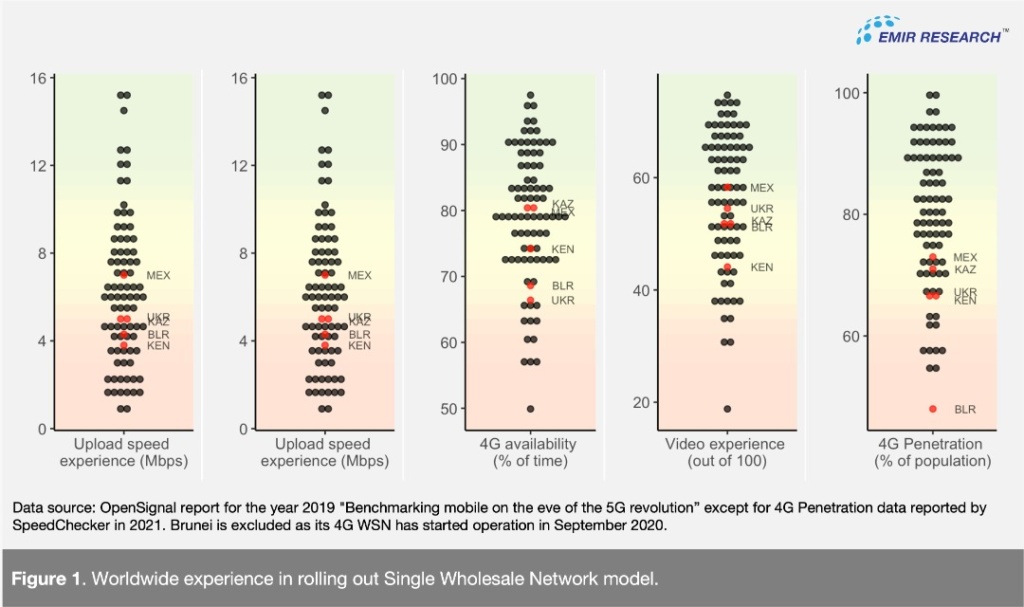

The last column in Table 2 speaks loudly for the “success” of the SWN / DWN model while Figure 1 visualises it. Regardless of the ownership structure (government or MNO consortium-led), it is still a monopoly, and therefore outcomes we observe in Figure 1 are rather expected. Please note in Figure 1 how Mexico has performed slightly better on the country level than the rest of the group, which is probably because, unlike in other countries, the excess 4G spectrum was auctioned to local MNOs.

Another important observation from Table 2 is that even for countries that tried the SWN model, there was never a notion of a “supply-driven” model! Pay attention to the Brunei case in Table 2 (unique and interesting), quoted by DNB. The CEO of Brunei’s Unified National Networks (UNN) specifically emphasised their demand-driven focus (on 4G and below) to recover investments while organically preparing the platform for the future (5G)!

So in the case of DNB, are we witnessing some “negative innovation” on top of the already proven to be problematic SWN (or even DWN) model?

Should it not be the case for international observers and investors to see the reversal of erroneous decisions more positively than sticking with it?

As per ABC of project management, reversing an erroneous decision/project is not a failure as much as it is successful resource management!

This makes the reported expression of caution by envoys of some of Malaysia’s top trading partners regarding the potential review of existing DNB contracts to be baffling. Malaysia should be free to conduct a neutral evaluation on the issue to independently determine what is best for the country without external pressures.

DNB claims that it had already engaged in commitments that would expose the government-owned entity to the enormous risks/implications (financial, legal and reputational implications, foreign direct investments, survivability etc.) should DNB explore any other models than it had committed itself to (which is a possible outcome of a constructive debate).

Are there really no other models or re-structuring options that do not necessarily mean breaking the contracts with Ericsson? It is unthinkable that any alternative suggestions would lead only to these extreme consequences.

Current responses from DNB appear to indicate that even if other parties can continuously prove DNB’s proposal as having serious flaws, the discourse is little too late. In all appearance, this sounds more like a desperate desire to bulldoze it through no matter what. “Too late” would be to wait a few years down the road to see financial losses and the devastating impact on the industry!

Given the conflict of business models (forcefully supply-driven versus intrinsically demand-driven), why would the MNOs or any private sector entity want to invest in DNB?

DNB’s claim that it’s/government is open to reducing its stake in 3 years is still unassuring.

Bearing in mind that it would still mean that any potential investor or stakeholder would still have to bear any financial burden and losses accumulated by DNB, especially in the rural areas!

Is DNB prepared to develop a winning formula that will ensure or guarantee that the switch from a supply-driven model to a demand-driven model be conducted successfully?

And then, government-led or consortium-led SWN, it is still the monopoly that is equally damaging to the industry. However, in the context of a highly corrupt country, government-led is undoubtedly a weaker proposition.

Is DNB admitting its existential awkwardness?

DNB opposes the creation of a second consortium-led SWN because it would not be able to compete with it and therefore cease to exist. Is this DNB admitting that another MNO-led consortium would do things better than DNB, yet it’s not needed for Malaysia? Should it not be the case that DNB would be able to compete given its claims to provide the best quality and lowest prices and that it has experts from the industry? Again, the claimed potential impact to DNB (financial, legal, and reputational issues) appears to be saying that it is too late to discuss which models work best for Malaysia.

As there are still unanswered questions, or at least, ongoing discourse and uncertainties surrounding the topic, the focus should be on addressing these queries whilst remaining open to alternative models. Convincing the public would then happen organically.

Despite these uncertainties, one thing is clear for now: 5G is marching successfully in those countries where solutions to such complex strategic decisions are born in open and honest dialogue as opposed to a government-imposed directive in corruption-ridden states—a dialogue in which the parties are radically transparent, hear each other and find, not always comfortable and smooth, but nevertheless mutually acceptable solutions beneficial for the nation as a whole.

Rais Hussin and Margarita Peredaryenko are part of the research team of EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.