Published in BusinessToday, Mysinchew, & AstroAwani, image by BusinessToday.

As policymakers continue reviewing the contentious DNB’s 5G rollout model, yet another set of fundamental questions to ask and evaluate critically revolves around Malaysia’s digital divide problem. Can the DNB’s model truly solve the national digital divide? Are there superior, more comprehensive and integrated alternatives to enable quality network connectivity nationwide? And if there are, WHY have they never been explored holistically ?

After all, EMIR Research would like to remind: the big claim to finally close (and close fast) Malaysia’s digital divide was the central premise of DNB creation. Two years have passed, and the public might have forgotten already. However, EMIR Research would like to bring us all back to the time of the early DNB’s wide-page advertorials loaded with big slogans — “we must close this urban-rural divide for 5G” and sort — and loud theses that DNB’s “supply-driven” Single Wholesale Network (SWN) model is the only way to force profit-driven telcos into non-financially feasible rural areas. We know now, as we know then, this is a complete and blatant lies, though it merits harsher rebuke.

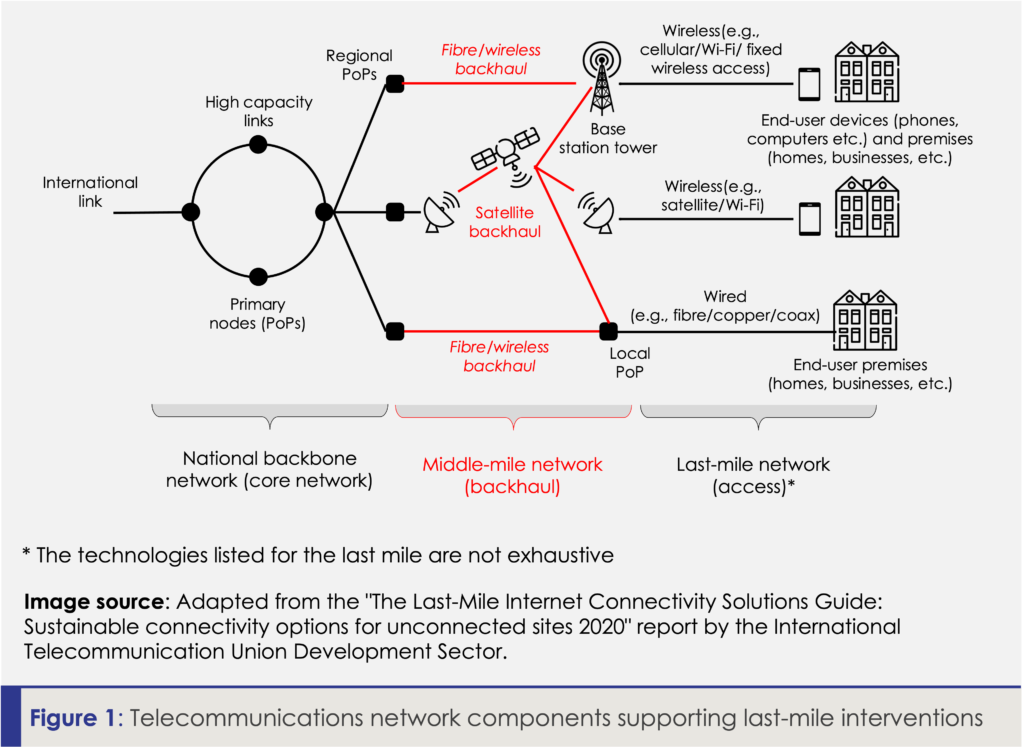

Figure 1 schematically outlines telecommunications network components supporting last-mile interventions in developing countries.

As we can see, backhaul — the transport link within the network that connects a tower or a local Point of Presence (PoP) with the core network — is that crucial piece of infrastructure which (if present) can be commonly used for various last-mile modes of service delivery to the end customer such as 4G, 5G, FTTx and WiFi.

ANYONE working long enough in Malaysia’s telecom industry should be well aware that Malaysia’s rural internet wounds are directly attributed to the inadequate presence or even complete lack of precisely this crucial network infrastructure element — the backhaul (mainly fibre one, which is superior). Dr Mohamed Awang Lah, the father of the Malaysian Internet, puts it the most succinctly: “Problems at the last-mile are just symptoms. The root cause is inadequate backhaul. This is a chronic disease. It is like blocked arteries and veins in the human body, but we are treating symptoms manifested in the capillaries”.

Nevertheless, previous significant nationwide initiatives, DNB included, continue to ignore the fibre backhaul problem and focus their efforts precisely on the last-mile — the capillaries. Ironically, even the National Fiberisation and Connectivity Plan (NFCP) was the fiberisation plan but only without a meaningful focus on fibre backhaul sharing, just like its successor, Jalinan Digital Negara (Jendela).

For example, according to Jendela’s latest available report, its digital infrastructure enhancement is all about the following items: fibre connectivity (fixed broadband), base station upgrades and new base stations, satellite connectivity, or local PoPs — all of these are last-mile infrastructure (refer Figure 1 again).

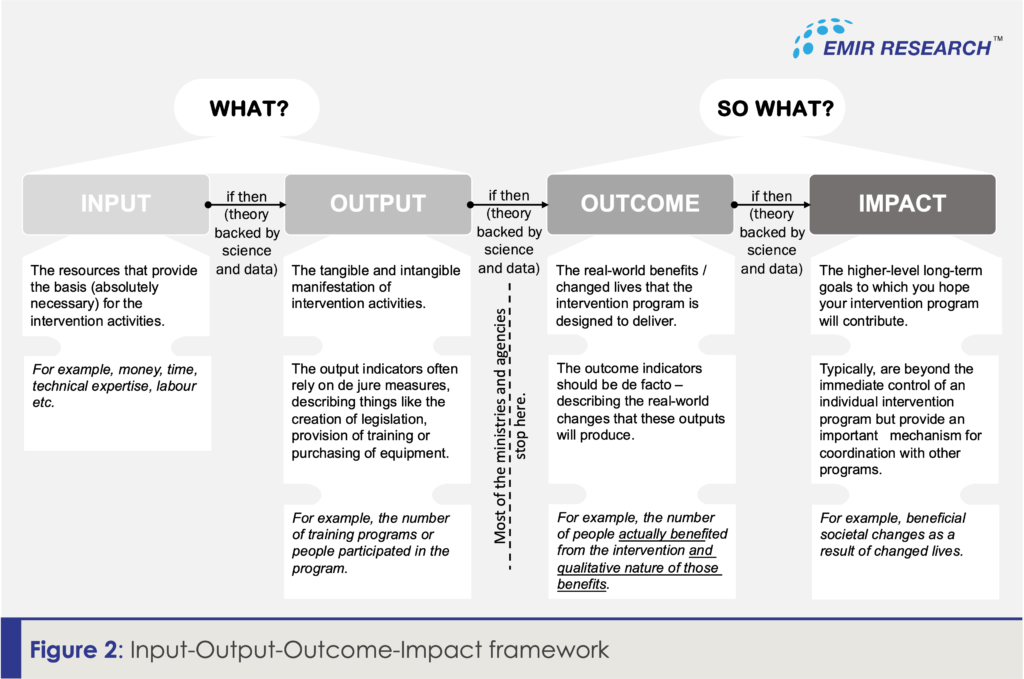

EMIR Research repeatedly highlighted this ever-persistent gap between the interventions and tangible societal outcomes and impacts, typical for third-world countries and a hallmark of Malaysia’s previous governance. As opposed to the Input-Output-Outcome-Impact framework (Figure 2) institutionalised by the first-world countries, in Malaysia, people’s money (inputs) has been splashed all this while for some kind of outputs not necessarily linked to the outcomes and impacts for the nation.

Similarly, EMIR Research has already highlighted that DNB, in the best traditions of this misplaced approach, does not provide an end-to-end solution sorely needed but focuses on the last mile only — counts towers and hastily inks contracts with Ericsson for 5G radio access network equipment. Therefore, how can the new rural areas be covered?

Under previously reported DNB’s cost structure, there is a fibre lease item (which in reality is bandwidth through fibre) from Telekom Malaysia (TM) budgeted for RM 1 billion, even though until today, it is unclear whether the budgeted amount is for the existing fibre or inclusive of new links needed to be extended to cover rural areas adequately.

Now keeping all the above in mind and looking again at Figure 1 carefully, the solution becomes crystal clear. There must be a neutral (not a retail player), government-owned entity to build or acquire and lease the backhaul infrastructure on a level playground basis to all the retail service providers to enable their competition for the last-mile, even in the most remote areas. This hub-and-spoke strategy will not only solve the digital divide but significantly increase competition in our telecom industry by eliminating the situation where lessees must compete against the lessor.

Therefore, DNB must be restructured to play the role of such a neutral, in the long-term self-financed, entity that focuses solely on passive backhaul infrastructure — dark fibre, towers and poles — build or acquire and lease out to retail service providers on a cost-plus basis. Furthermore, the unit rate should be per fibre link or km, not per Gbps, to future-proof the data transmission cost as, with the increased volume, per Gbps cost can be reduced significantly for the benefit of the end-users as was discussed in EMIR Research earlier article (refer to “Malaysian 5G Rollout: Camouflaged Costing Acrobatics”).

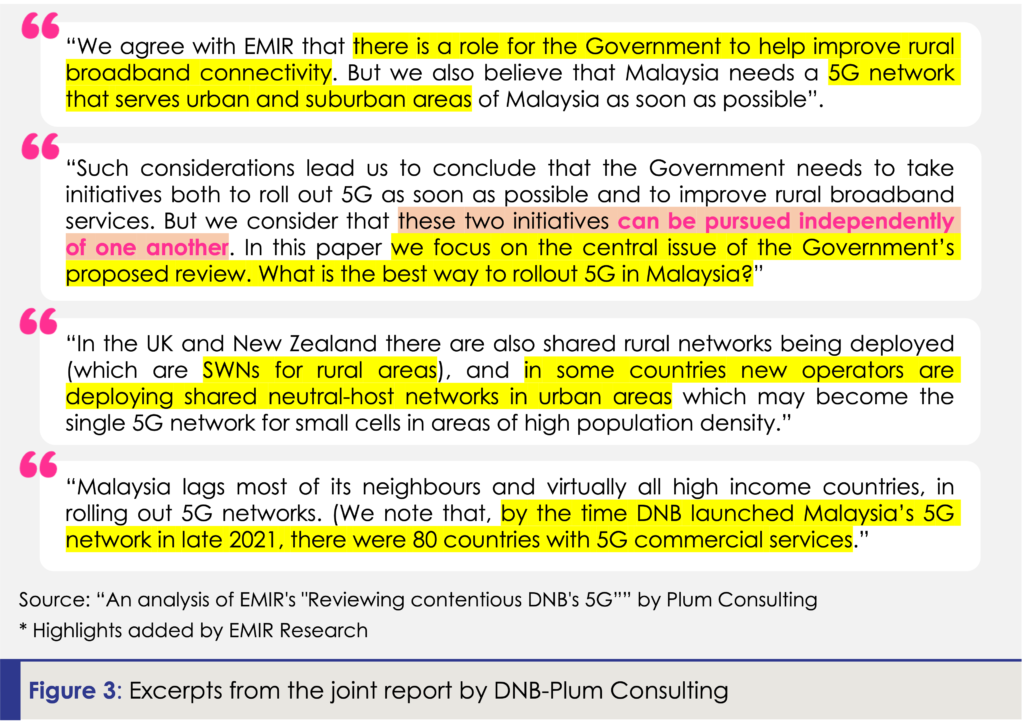

As icing on the cake, DNB, with the Plum consultancy’s help though, no longer disagree with EMIR Research in their recent report (refer to “An analysis of EMIR’s “Reviewing contentious DNB’s 5G””) — word to word quotes taken from this report are in Figure 3.

What a sudden change of tone for the main narrative — now DNB is no longer about solving the digital divide problem, which can be pursued as an independent initiative. Good to finally hear this from the DNB itself — the policymakers should, certainly, appreciate this.

The only problem is that we knew this from the very beginning, and here the last quote in Figure 2 is very significant. Only Plum forgets to clarify, entirely truthfully, that Malaysia’s 5G rollout lag behind the rest of the world was precisely caused by the DNB creation because, by the time DNB launched, none of those 80 countries pursued problematic SWN for their nationwide 5G rollout. Some did limit SWN to rural areas (which DNB is not doing). The rest few who pushed SWN nationwide even for 4G have miserably failed (refer to “Malaysian 5G Rollout “Unanswerable” Questions” for detailed empirical data) except Brunei, a country with a tiny population.

Malaysia could have done the same — auction the 5G spectrum to MNOs who were already well prepared to quickly and less costly than DNB (see “Malaysian 5G Rollout: Camouflaged Costing Acrobatics”) upgrade their network to 5G as early as mid of 2019. In fact, they could have done so even with their existing 4G spectrum (not forget that the 3G spectrum can now also be repurposed) if the previous government had not suddenly withdrawn the spectrum neutrality concurrently with pursuing the contentious SWN by DNB. So at least in urban and suburban areas, where telcos’ 4G towers are already omnipresent, 5G could have sprung in early 2020, paving the way for Malaysia’s 4IR industrialisation.

“How about the digital divide then?” — you would exclaim. Right, if DNB was so concerned about it, then why instead of focusing on rural areas, they rushed to urban and suburban areas, though until now, we see not much progress in rural areas (as well as in urban, except arbitrary reported unverified figures, among other things)? Well, now they are telling us openly — digital divide is a separate initiative! As usual, the underserved and marginalised were used on a temporary basis for narrative purposes to advance someone else’s interests.

But DNB is right on one thing — there shall no longer be a delay for credible 5G rollout and elimination of the digital divide. But immediate restructuring DNB is paramount to achieving both these objectives.

Note that restructuring DNB would not cause a delay for the 5G rollout, penalties or write off any work, if any, completed by DNB thus far, as EMIR Research already explained in its earlier writings (refer to “The Impeding Failure of Good Intentions: DNB’s 5G Roll out — Part 2”)!

As for rural areas, extending adequate fibre backhaul infrastructure would take some time. Nevertheless even in the temporary absence of such a critical piece of infrastructure, something can be done reasonably quickly to credibly restore the right of rural dwellers to quality network access.

The policymakers should pay urgent attention to the piece by Dr Mohamed Awang Lah titled “Cheaper solution for rural broadband”. The renowned veteran of Malaysia’s telecoms/internet industry suggested an easier, cheaper, and, importantly, fast solution for even the smallest villages and villages without electricity to have WiFi connection as fast as in towns to address their user needs! Now, almost all mobile and desktop devices support WiFi. This way, the schools, even in the smallest villages, can have fast Internet soon! Much sooner than under the contentious DNB with its unrealistic “supply-driven” model!

After all, even past two years of bravado about their jihad to bridge Malaysia’s digital divide DNB still focuses on highly populated urban areas in the best traditions of “input and some output not linked to the best outcomes and impacts for the nation” paradigm. It is time to finally break away from this paradigm and do something for the people based on data, science and economics. Monumental white wash at the nation and peoples expense !

Dr Rais Hussin is the president and chief executive officer of EMIR Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research. He is now attending the Mobile World Congress 2023 in Barcelona sharing his views on 5G and 6G.