Published in TheStar & AstroAwani, image by AstroAwani.

William James, a philosopher and psychologist and a key figure in the American scientific revolution at the dawn of the 20th century, once wrote about the importance of a nation collecting a “critical mass of men of genius” who could make an entire civilization, not just their nation, “vibrate and shake!”

While the negative effects of brain drain are well-documented, it’s crucial to recognize the potential benefits. This nuanced and multi-dimensional issue not only poses challenges but also unique opportunities for strategic economic development.

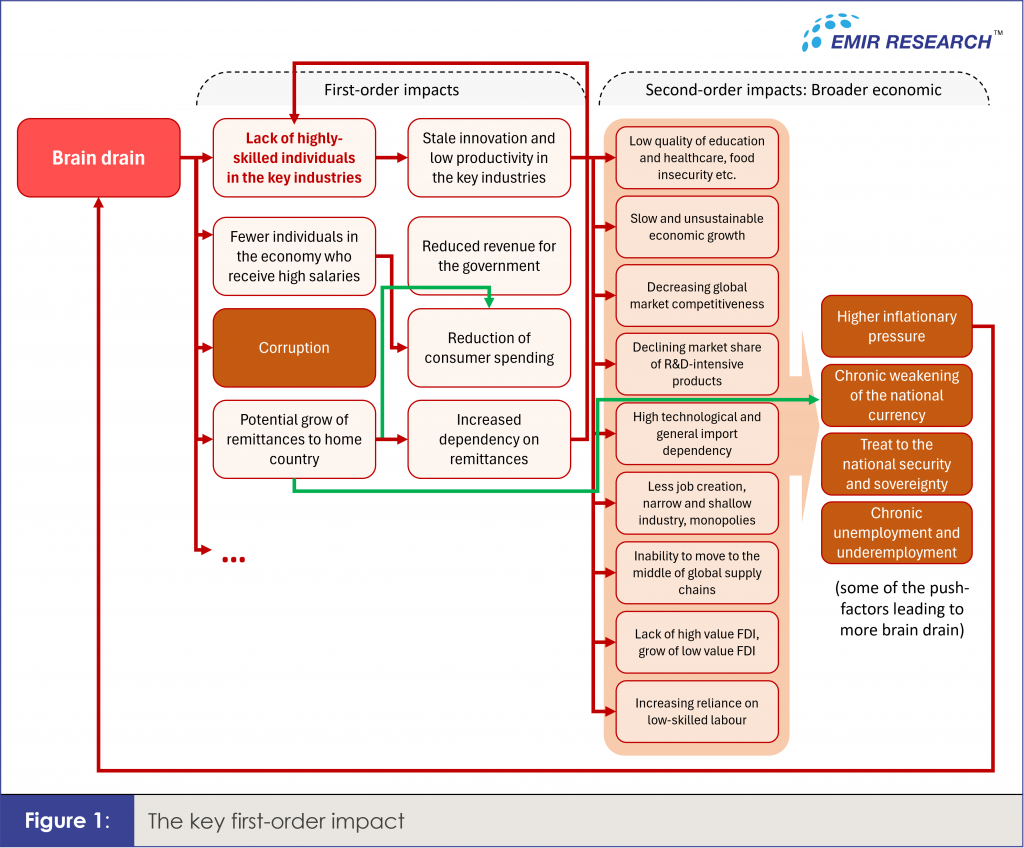

As an immediate and key impact, brain drain results in a severe shortage of highly skilled individuals in critical sectors, including healthcare, education, technology, research and development, engineering, and food security. This shortfall can significantly constrain a country’s capacity for innovation, diminish productivity, flexibility and efficiency, and impede economic growth, resulting in various adverse effects on the overall economy (Figure 1).

Notably, brain drain demonstrates positive selection, with the best and brightest often leaving first – other countries’ prime opportunity to attract top talent.

Consequently, the skill and knowledge gaps typically occur first in industries critical to sustaining global competitiveness. As a result, the donor country experiences decreasing global competitiveness, a declining global market share of R&D-intensive products, high technological and general import dependency (threatening its national security and sovereignty), and an inability to move up the global supply chains. Conversely, the country becomes locked at either end of the supply chain (e.g., raw materials or simply an assembly of finished goods) while increasingly relying on low-skilled labour and low-value foreign direct investments (FDI) that perpetuate this dependency.

Malaysia’s big challenge in attracting high-value FDIs was already evident in the early 2010s, with numerous local reports of MNCs struggling to recruit highly skilled individuals locally.

Because highly skilled and educated individuals often drive innovation and entrepreneurship in the country, their mass departure also severely reduces job creation, leading to a narrow and shallow industry that deviates from global trends and experiences chronic unemployment and underemployment. This situation also fosters the growth of monopolies.

As a result, the government faces lower, riskier, and unsustainable revenue, making it even more challenging to adequately support deteriorating sectors critical to human development and quality of life, such as education, healthcare, and public services.

Brain drain also substantially diminishes government revenue, as it is predominantly the highly skilled professionals—who are the higher income earners—that depart. These individuals are also the primary contributors to surplus spending within the economy. Consequently, a mass exodus not only contracts the income tax base (amount and size) but also curtails consumer spending, thereby further inhibiting industrial expansion.

Furthermore, shrinking economic activity and import dependency coupled with a constantly expanding monetary base (primarily in the form of credit) fuels inflation. Simultaneously, the inability to engage in higher-value segments of global supply chains and import dependency exacerbate the weakening national currency, creating yet another chronic challenge.

While remittances by the Malaysian diaspora may somewhat bolster consumer spending and the national currency, Malaysia’s large migrant workforce, with a historically estimated equal ratio of documented to undocumented workers and 2.1 million documented foreign workers in 2020, suggests that outflow remittances could offset any gains from Malaysian migrants’ remittances.

Over-reliance on remittances risks becoming entrenched, deterring skill advancement—amplified by the gig economy’s rise—and aggravating the shortage of skilled professionals, triggering a cascade of adverse economic effects (Figure 1).

Related to the remittances debate, if we imagine even a fraction of the multimillion-dollar sum sent home by emigrants eventually invested in R&D, might not opportunities for highly skilled and educated nationals improve at home? Perhaps, but in an economy where resource allocation is governed by data, science, and economic principles, thereby reducing the potential for corruption.

However, it is a compelling paradox that widespread corruption, while recognized as a primary driving force behind the global brain drain, is simultaneously a very direct result of it.

Every thriving economy requires an ample workforce of skilled professionals, such as engineers and doctors, who, drawing on data, scientific principles, and economic theories, are adept at employing resources in the most effective and efficient manner. This begs the question: what would happen to a resources-rich nation (like Malaysia) when it lacks the necessary human capital to utilize these resources optimally for the country’s benefit? The apparent consequence is an increase in speed-to-spend and widespread corruption.

Furthermore, good accountants are essential to effective resource management. However, it is a well-known fact that Malaysia has been experiencing a shortage of accountants since the early 2010s due to persistent brain drain. Meanwhile, a shortage of accountants can also severely disrupt industries, with firms struggling to maintain financial records and comply with standards, increasing the risk of corporate scandals and weakening investor confidence, thereby deterring FDI.

Notably, corruption, chronic skill mismatch, job scarcity, inflation, currency depreciation, and deteriorating quality of life all serve as typical push factors for brain drain both globally and within the Malaysian context (as discussed in “Malaysian Brain Drain: Voices Echoing through Research”). However, it is important to recognize that brain drain itself is the key factor leading to these broad negative and persistent economic problems (Figure 1). Thus, addressing the issue of brain drain is essential for finding solutions.

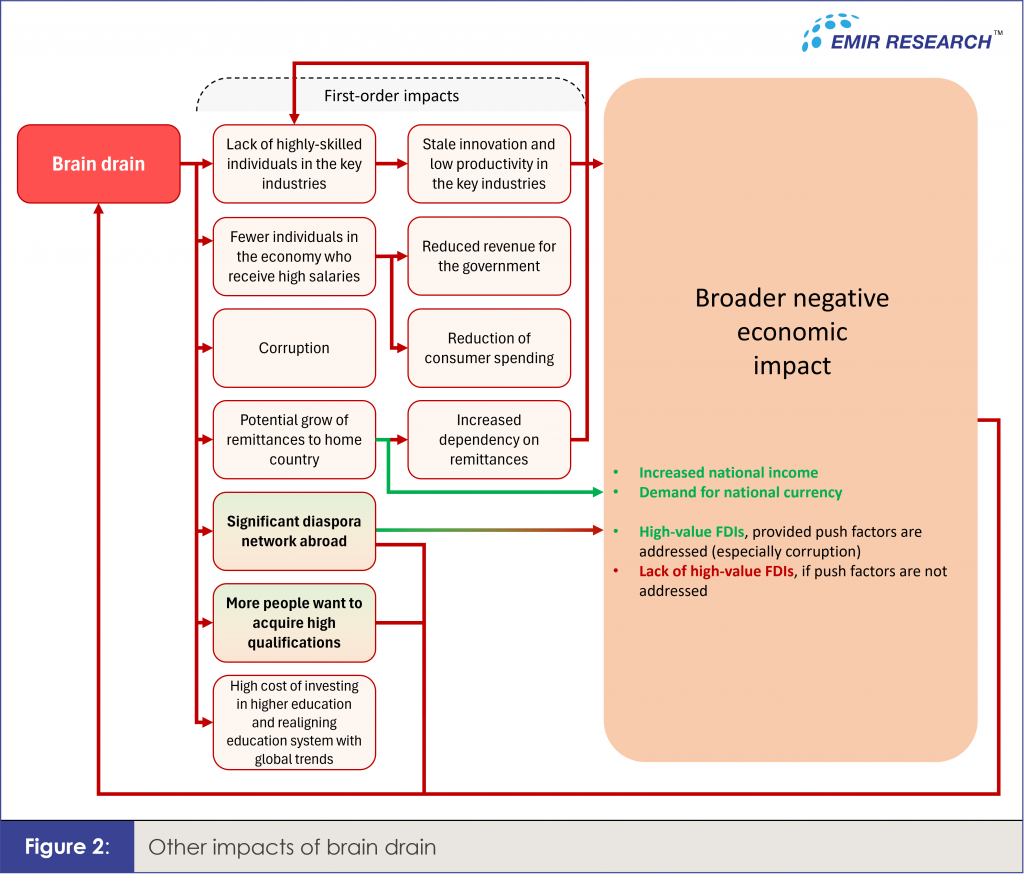

Therefore, it is interesting to look at other impacts of the brain drain (Figure 2) that might not be exclusively bad for a country and, in fact, offer contingent advantages and pave the way for strategic brain gain.

The longstanding issue of Malaysian brain drain has led to a substantial diaspora, which now tends to exacerbate the issue yet through chain migration.

At the same time, migrant-established networks abroad often lower informational barriers, potentially boosting foreigners’ interest in travelling to, investing in or in other ways engaging with their home country.

However, this benefit is unlikely to be realised when the factors driving individuals from their homeland are as pervasive and ingrained as the issues Malaysia has grappled with for decades – the most toxic ones are widespread corruption and deep-seated identity politics.

In fact, we should expect quite the opposite dynamic – extensive diaspora presence may contribute significantly to deterring high-value FDIs. This is likely to continue unless and until the key brain drain-pushing factors are addressed!

Once the key pushing factors are addressed, a significant Malaysian diaspora network can be then engaged strategically to plug critical skills and knowledge gaps in the local industry. This may not require their physical return—which demands deeper systemic changes and time—but could involve their participation on a project-by-project basis.

Also, brain drain often motivates many to pursue advanced qualifications for migration opportunities, yet not all will leave, presenting a latent talent pool. Nonetheless, this scenario is not without its challenges: the country must be able to 1) utilize its human capital effectively, 2) provide access to high-quality education, and 3) implement measures that make emigration challenging, which, as a minimum, again requires the absence of most fundamental push factors.

Enrolment in Malaysian tertiary institutions has declined since 2015, indicative of a deteriorating education quality, among other things. Additionally, pursuing higher education overseas significantly contributes to Malaysia’s brain drain. Therefore, urgently reforming the Malaysian education system, as detailed in “Urgent Need to Reform Malaysian Education System,” is integral to mitigating the brain drain.

However, it is crucial to note: again, without addressing other key toxic push factors driving Malaysia’s brain drain, investing in the education system, as well as all skill-enhancement and retraining programs, is akin to subsidising foreign economies, as individuals will continue to emigrate.

Aligning Malaysia’s education system with global trends is essential to address the brain drain. Yet, while this alignment should foster versatile, tech-savvy professionals ready to navigate (and switch between) diverse industries—as discussed in “The Future Economy: Reinventing Malaysian Educational System”—it also risks making them even more attractive to foreign markets. This once again underscores the critical need to tackle the underlying factors that contribute to Malaysia’s brain drain in its entirety.

In sum, Malaysia’s pronounced brain drain increasingly transpires as the fundamental factor underlying the country’s most pressing socio-economic challenges. Although this exodus of talent can create distinct opportunities for economic growth, Malaysia stands to miss these benefits without a strategic response to the driving forces of brain drain presented by EMIR Research in its “Malaysian Brain Drain: Voices Echoing through Research” report.

Meanwhile, as the adage goes, “time and tide wait for no man,” and our nation’s most brilliant minds persist in “vibrating and shaking” other countries, leaving a palpable void in their homeland.

Dr Rais Hussin is the Founder of EMIR Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.