Published by AstroAwani & MYsinchew, image by AstroAwani.

The definition of terrorism has evolved throughout history, shaped by socio-political contexts like revolutions, regimes, repressions, and wars. However, creating a universally applicable yet specific and practical definition remains central to effective public security strategies.

During the launch of the Malaysian Action Plan on Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism (MyPCVE) in September, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim emphasised a primary challenge shared by many nations: a lack of understanding of the background and root causes of terrorism.

States urgently seek effective counter-terrorism strategies, but the complexity of terrorism—stemming from its multifaceted nature and absence of a universal definition—makes it a phenomenon that is not easy to capture.

Meanwhile, even a brief thematic content analysis of both empirical research and conceptual discussions on the definition of terrorism reveals common themes across various definitions, offering valuable insights for developing a more holistic and proactive national defence policy.

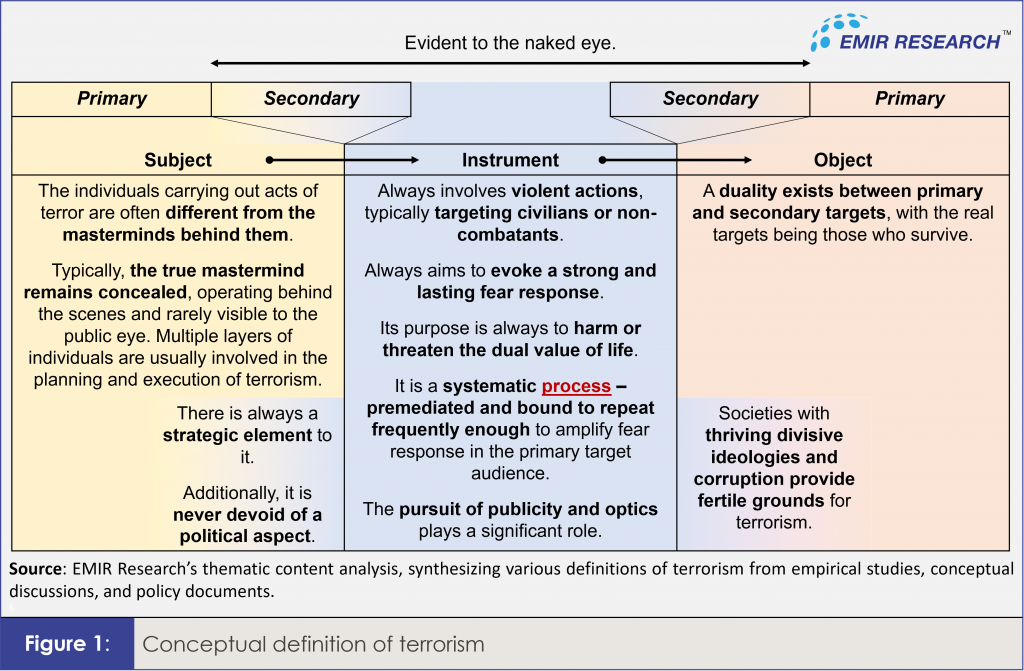

Figure 1 schematically illustrates the key elements common to various definitions of terrorism and shows how they are interrelated.

The systematic nature of terrorism

Terrorism is widely concurred as the deliberate and systematic use or threat of violence designed to create an atmosphere of terror or fear to publicise a cause and compel political compliance. It is always a premeditated form of violence intended to incite panic by endangering the “dual value of life”—both one’s own life and the lives of others—through acts such as hostage-taking, murder, injury, and the destruction of public property.

Furthermore, terrorism is a vehicle of psychological manipulation, leveraging fear—one of the most potent human emotions, which significantly affects cognition—causing individuals to think less critically, act irrationally, and make impulsive decisions. This psychological effect constitutes a core aspect of terrorism (Merari,1993). It is driven by the unpredictability of indiscriminate violence, which triggers deep-seated feelings of insecurity and vulnerability. Consequently, individuals tend to evaluate risks instinctively rather than rationally, often magnifying the perceived threats (Gillani, 2022).

Moreover, Schmid’s interpretation of terrorism as an anxiety-inducing strategy, characterised by repeated acts of violence, reinforces the concept of terrorism as a “systematic process”. In other words, an act of terror is seldom a random, isolated event; rather, it is bound to recur frequently enough to evoke a strong fear response, even through a mere threat of violence. This notion supports the view of some scholars that the threat of violence alone can be classified as terrorism.

As a policy implication, the premeditated and systematic nature of terrorism (as a phenomenon that gradually evolves over time and space) emphasises the need for a deeper understanding (through research) of both the broader pathways to terrorism, its stages and the specific factors driving each isolated act of terror, which can vary fluidly across incidents. This also underscores the paramount centrality of early detection systems.

The duality of subject and object of terrorism

Schmid (2023) describes terrorism as a series of assassinations designed to instil fear, with victims serving as mere instruments—a theme universally shared by many definitions of terrorism. The term “instrument” implies the existence of a “master” who created and uses this tool, also the primary subject behind the action. Meanwhile, those who actually execute the act of terror (secondary subjects) themselves constitute the part of the instrument (Figure 1). In other words, there’s a duality in the subjects of terrorism: the “optical” (visible on the surface) and the hidden (the grand mastermind). Often, multiple layers of actors are involved. To differentiate them, we must consider a wider context: the chain of events before and after the act, their causal links, possible motives, and, importantly, the entities that emerge as the primary beneficiaries —all suggesting a deliberate strategy.

The same duality or multi-layer nature applies to the objects of terrorism. Terrorism communicates through direct and indirect targeting. It is a form of political violence that spreads fear beyond the immediate victims (Held, 2004)—“its main object is not those who became victims, but those who survived” (Kara-Murza, 1999).

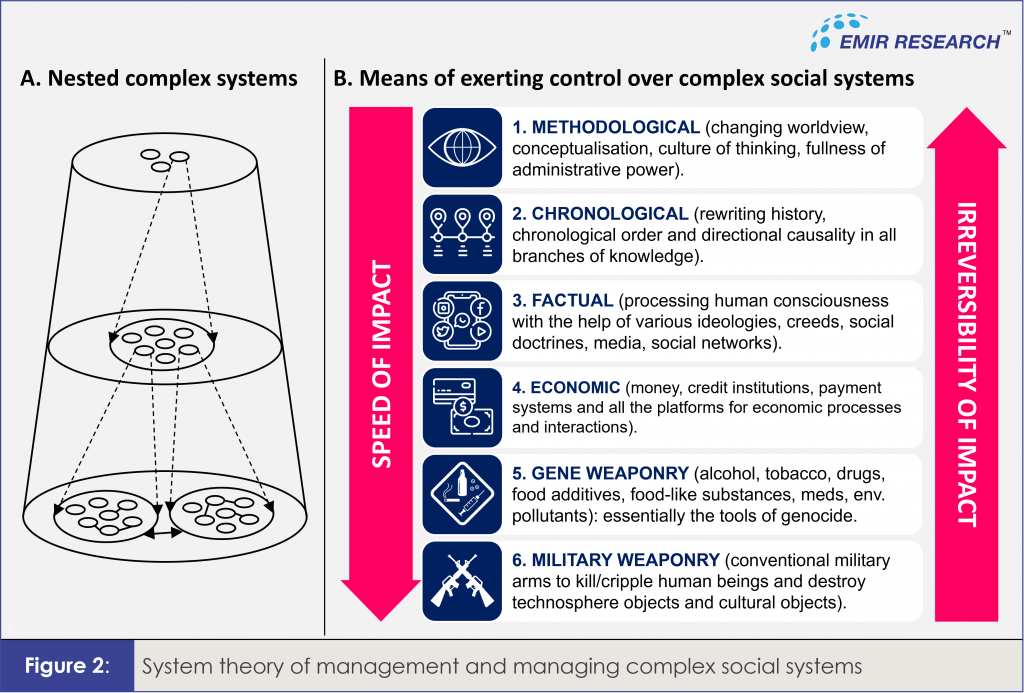

All of this aligns well with the general systems theory, which operates within a framework of nested complex systems (Figure 2A), where each system is influenced by control exerted by higher-order system(s), often in ways that are obscure to lower levels. In the context of complex social systems, the full range of tools for exerting control is presented in Figure 2B, where terrorism can be attributed to gene weaponry.

Figure 2 serves as a crucial input for designing effective early-detection intervention policies.

Furthermore, in line with systems theory, every individual actor in an act of terror can simultaneously be both a subject and an object, either knowingly or unknowingly.

According to the literature on the definition of terrorism, actors may include states (governments or opposition), political parties, sub- or supra-national governance structures, international organisations and even clandestine agents.

The strategic and political element to it

One of the key themes common to many definitions of terrorism is that politics plays an integral role (Weinberg et al., 2004). As English (2009) notes, the centrality of politics and power is imperative to any definition of terrorism. Relatedly, an overwhelming number of definitions use terms such as “strategy”, “goals” or “tactics” as primary descriptors of terrorism. This strongly suggests the concealed presence of a broader vision, mission, and strategy, and ultimately echoes the conceptualisation of terrorism as an instrument or tool, as discussed earlier.

In the same vein, Chomsky (2002) broadens the concept of terrorism by incorporating religion and ideology. Ideology can powerfully define an in-group or out-group, encompassing “religion”, “ethnicity”, “political views” or other deeply held beliefs—any levers that can then be skilfully manipulated to polarise a society in pursuit of self-serving goals.

This is why, although terrorism can be classified as a form of “gene weaponry” (see Figure 2B again), it is ultimately bred at a higher level of weaponry by systematically shaping human consciousness through ideologies, which takes a long time to develop but is difficult to reverse.

This also intertwines terrorism with identity politics.

Interestingly, many definitions of terrorism, whether explicitly or implicitly, include an element of “fight” related to its political aspect. This fight, particularly when conducted through violent means in line with Machiavelli’s notion that “the end justifies the means,” is always directed towards securing generally resources with the intent of unlawful expropriation.

This has heavy implications for public security policy: resource-rich countries that fail to utilise their resources productively—guided by data, science, and economics—due to rampant corruption, clearly invite the threat of terrorism to their lands.

After all, identity politics and corruption are twin evils that must both be relentlessly eradicated for yet another reason—to mitigate the threat of terrorism. Therefore, comprehensive national policies aimed at fostering national unity and combating corruption should supplement or even be integrated as strategic components within Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism (P/CVE) frameworks.

Another important takeaway from the comprehensive definition of terrorism is the dire need to cultivate conceptually powerful policymakers and a well-informed public who can easily discern the duality of subject and object in every act of terrorism. Therefore, discussing each topic in courses related to complex social systems, such as Public Relationships and International Issues, is simply impossible out of the context of systems theory briefly discussed above!

Ultimately, some things may elude us not due to the weakness of our concepts, but because they fall beyond our conceptual grasp. It is the clarity and breadth of our understanding that enable us to pursue our own goals. Conversely, misunderstanding or ignorance can lead us to unknowingly become a mere instruments in the pursuit of someone else’s goals.

Dr Margarita Peredaryenko and Avyce Heng are part of the research team at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.