Published in Business Today & Asia News Today, image by Business Today.

The expected dividend declaration (conventional) by EPF for the year 2021 of about 5.2% to 6% is remarkable considering that it’s the second year of the on-going Covid-19 pandemic with the lockdowns, dampened economic momentum, and global supply-chain bottlenecks. EPF’s Shariah-compliant investments dividend declaration is expected to be at 4.9% or thereabouts.

This follows EPF’s announcement that its total gross investment income for 9 months last year (9M 2021) which ended in September was RM48.02 billion – an increase of 7.7% or RM3.42 billion as compared to the RM44.60 billion recorded for the same period in 2020.

Equities continued to be the main income contributor, accounting for 54% of total gross investment income at RM7.5 billion.

All this set against the wider backdrop of a generally low interest rate environment globally – as “forefronted” by the developed economies, that is.

As such, there’s simply no correlation between higher returns and higher rate of interest at all (when considering investment decisions).

Historically, EPF has done very well in a low interest rate environment that has lingered since the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008/2009 – what mainstream economists and commentators dub as “secular stagnation”, i.e., low interest rate coupled with sustained low inflation (until now, of course).

This shouldn’t have come as a surprise. Gibson’s Paradox had already encapsulated such a phenomenon – an insight incorporated by Keynes into his analysis.

Although Gibson’s Paradox was based on an observed, long-run, positive correlation between interest rates and the price levels in the UK under what was the gold standard then, it can’t be strongly emphasised enough that the underlying dynamics are the same, namely that the growth of the money supply is endogenous (demand-driven).

The following is a brief and quick survey of selected central bank’s policy interest rate movements (as representative of the developed economies) since the GFC.

In December 2008, the Federal Reserve set a target range of between 0% to 0.25% for the federal funds rate. Over the years, the federal funds rate has averaged 0.8% – with the 0% to 0.25% making its comeback in 2020.

Across the Atlantic Pond, although the Bank of England’s bank rate was at 5.5% in December 2007, i.e., two months after the nationalisation of Northern Rock which was supposed to have been the harbinger of the GFC, this was progressively reduced to as low as 0.5% by 2009. And in 2016, the bank rate went down to 0.25% with the lowest ever being 0.1% in 2020.

Over in the UK’s former “alma mater” as well as “overlord”, i.e., the EU, the European Central Bank (ECB) has three policy interest rates. These are the a) the interest rate on the main refinancing operations (MRO) – which provide the bulk of liquidity to the banking system; b) the rate on the deposit facility – which banks may use to make overnight deposits with the Eurosystem; and c) the rate on the marginal lending facility – which offers overnight credit to banks from the Eurosystem.

Using the MRO as proxy (since this will directly influence the horizontal interbank lending in the member-states of the Eurosystem because it’s the main source of financing for the vertical credit system within the framework comprising of national central banks or NCBs), the ECB started off with 3.75% in 2008. The MRO was steadily lowered to 1.25% in 2009 and became “range-bound” soon after until 2012 where it further dropped to 0.05 in 2014. The MRO has stayed at 0% since 2016.

It’s a double irony given that on the one hand, ultra-low interest rates have not generated the level of inflation at 2% (over the medium term) as expected by the ECB given its commitment to Monetarism. Inflation overshoot, as it is, has been due to the current (transitory) cost-push inflationary phenomenon.

On the other hand, the ECB’s bond purchase programmes (its own version of quantitative easing or QE) which then reduces the long-term yields of the sovereign issuers had become, in effect, a form of back-door deficit financing (of the member-states concerned) – again “anathema” to the Monetarist ideology and the constitutional commitments to the Stability and Growth Pact (“monetary dominance”).

Be that as it may, notwithstanding, the ECB has acknowledged that “… the interaction between monetary and fiscal policy has changed in the low interest rate environment … In this environment, fiscal policy gains importance” (“The ECB’s independence in times of mounting public debt”, European Central Bank, October 10, 2020).

For December 2021, headline inflation (5%) in the EU remains asymmetrical from core inflation (1.4%). That is, there’s no discernible parallel movements between the two which should give cause for real concern. This from the low base of 1.4% and 1.2%, respectively, at the start of 2020.

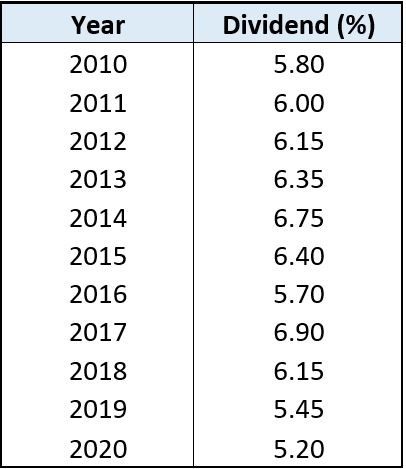

The ultra-low interest rate coupled with a low inflation environment in these economies have not affected EPF’s returns as reflected in the dividend declarations (please refer to Figure 1).

Domestically, Bank Negara started off at 3.50% in 2008, but lowered the Overnight Policy Rate (OPR) in common with the three central banks albeit less steadily and extensively – a mean (average) of 2.50% from 2009 to 2011 – only to switch back to 3.00% later in that year (i.e., 2011). Our OPR has been at 1.75% since 2020.

Figure 1: Performance of EPF dividend (credit: Tan Tze Yong)

According to then EPF CEO Tunku Alizakri Alias (now Chairman of the Board at Malaysia Venture Capital Management Berhad/Mavcap), foreign assets had returned 8.64% last year, as against the 5.02% yielded by domestic assets (“EPF to continue foreign asset push after solid year”, Asian Investor, March 2, 2021).

As at end-September 2021, overseas investments make up 36% of EPF’s RM988.55 billion in total assets. They contributed close to RM28 billion or 58.2% of total gross investment income in 9M2021. This is higher than its 49.8% contribution to gross investment income for the whole of 2020, where overseas assets made up 35.14% of total assets.

Under current EPF CEO Datuk Seri Amir Hamzah Azizan, overseas investments will be augmented – despite one school of thought advocating for EPF to repatriate funds to invest more locally. On the other hand, this would reduce the tax receipts for foreign-sourced income which exemption has been removed under Budget 2022 by Finance Minister Tengku Zafrul.

The UK is one country that EPF has been eyeing and one of the top five countries for overseas investments. As at end-2018, EPF’s investments in the UK accounted for 3% of its total investment assets which amounted to RM25 billion.

The success of the Battersea Power Station (developed by a consortium comprising SP Setia Bhd, Sime Darby Property and EPF) has encouraged EPF to look into other areas of investments such as the real estate and office assets market because of the multiplier and spillover effects in the form of urban regeneration and redevelopment in central London.

EPF’s key investments in the EU are in member-states such as Germany and France.

Other sources of investments include Australia (e.g., Dexus Healthcare Wholesale Property Fund/HWPF – an Australian healthcare real estate management fund) and North America (e.g., Kwasa Infrastructure Sapphire – infrastructure investment holding company. In 2020, EPF injected capital amounting to USD80.14 million/ RM337.12 million into Kwasa Infrastructure Sapphire for investment in a leading global fibre provider with substantial network and presence throughout the US, Canada and Europe, as per EPF Annual Report, 2020).

When compared to Singapore’s Central Provident Fund (CPF), it’s pays out a multi-tiered divided – comprising the Ordinary Account, Special and MediSave Account and Retirement Account. The CPF pays out a minimum (the floor) rate of 2.5%, 4% and 4%, respectively.

For those aged 55 and above, the government pays an extra 2% interest on the first SGD30,000 of their combined balances – capped at SGD20,000 for Ordinary Accounts. The government will also pay an extra 1% on the next SGD30,000. This means CPF contributors will earn up to 6% interest per year on their retirement balances.

Perhaps, our government can look into the doing something similar (for Accounts 1 & 2) for those whose EPF savings have been diminished by the withdrawal schemes or aren’t able to catch up in the lead up to retirement age.

Moving on, we also need to look very seriously into setting up a SWF for the purpose of maximising returns on our national wealth for the government on behalf of the nation/people as a whole – which can then be deployed to fund our KWAP (public sector pensions fund) and, secondarily, top up EPF accounts.

Our EPF should not be treated as substitute for a sovereign wealth fund (SWF), notwithstanding its successful Strategic Asset Allocation (SAA) investment decision-making process “algorithm”.

An eminent example is none other than Norway’s Government Pension Fund (GPFN) comprising the global (world’s largest) and domestic SWFs. Just last year, the global arm generated a rough equivalent to USD176.6 billion in returns. Overall, GPFN is valued at USD1.4 trillion – worth around USD250,000 per capita/person.

To conclude, EPF’s consistent and continual excellent performance is due to its technical and financial judgment. Therefore, the superior judgment of the EPF should always prevail over that of any politician (or even policy maker who’s not involved in EPF). This includes calls to serve a particular (politicised) agenda.

Kudos and keep up the good work, EPF!

Jason Loh Seong Wei is Head of Social, Law & Human Rights at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focussed on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.