Published by AsiaNewsToday, BusinessToday & AstroAwani, image by BusinessToday.

e-Waste or “Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment” (WEEE) refers to any discarded electronic item and is one of the fastest growing waste streams globally.

While e-waste generation continues to increase due to rapid technological innovation and savvy marketing strategies, the lifespan/life cycle of these electrical and electronic products continues to shorten (“Sustainable e-waste management in Malaysia: Lessons from selected countries”, Shad et al., IIUM Law Journal, Vol. 28, Issue 2, 2020). Only 20% of global e-waste is recycled.

Some 44.7 million tonnes of e-waste were produced worldwide in 2016 (“An analysis of electronic waste management strategies and recycling operations in Malaysia: Challenges and future prospects”, Yong et al., Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 224, Issue 4, 2019).

In Malaysia, 280,000 tonnes overall or representing 8.8kg of e-waste per person were produced. As Malaysia transitions from a middle-high to a high-income country, e-waste is only expected to increase (“The Global e-Waste Monitor 2020”, Forti et al).

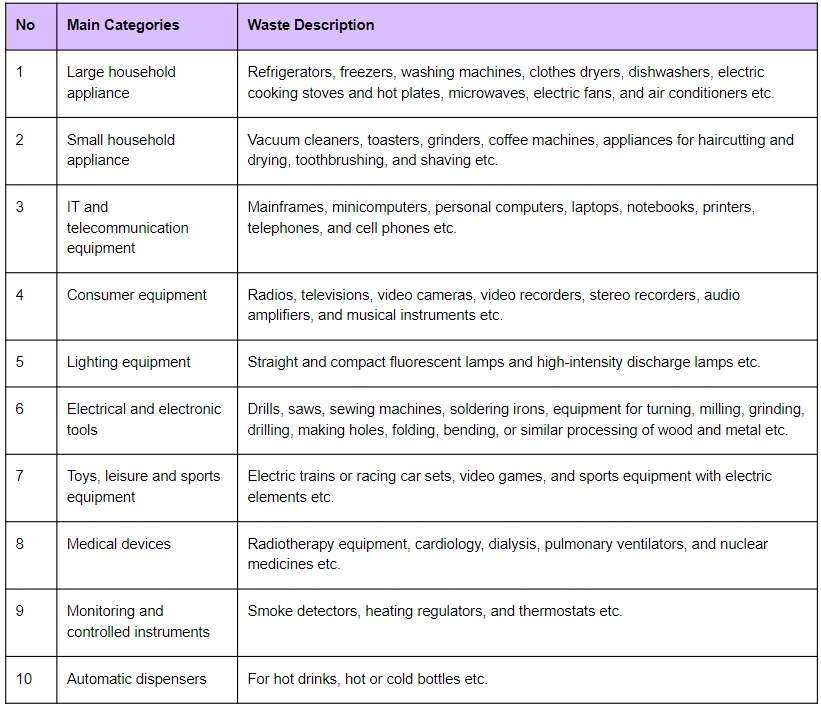

Currently, Malaysia includes six items only when defining e-waste: mobile phones, computer/laptops, television, air-conditioner, refrigerator, and washing machine/dryer.

This list isn’t exhaustive compared to how the EU defines e-waste (see Table 1).

Source: Directive 20212/19/EU on WEEE

Health Impacts of e-Waste

e-Waste contains numerous metals and toxins (such as mercury, lead, arsenic, cadmium, and flame retardants). Communities around unregulated e-waste recycling areas and e-waste employees report increased instances of DNA damage, altered neuro-development, spontaneous abortions, premature babies, skin diseases, hearing loss, dizziness, shortness of breath and male reproductive and genital disorders.

e-Waste that’s left untreated or is treated unsafely can cause the toxins to contaminate water, air, and soil. Toxins leach into soil and enter plants which when consumed increases cancer and live and kidney damage risk. Breathing this polluted air or drinking this polluted water can lead to cardiovascular and respiratory diseases (“Infographics”, E-waste Management in Malaysia).

Transboundary Movements of e-Waste

Because of these adverse health impacts countries prefer exporting their e-waste to other countries.

Around 60-90% of e-waste are illegally shipped to developing countries or less developed countries annually. Over 350,000 million tonnes are shipped from the EU yearly . Ever since China banned e-waste imports in 2018, other Asian countries including Malaysia have become popular e-waste dumping destinations.

The import and export of e-waste is banned in Malaysia since 2012 and 2017, respectively, unless approved by the Department of Environment (DOE).

Informal e-Waste Recycling in Malaysia

More than 1,000 containers carrying tonnes of e-waste are illegally imported monthly and processed in Malaysia (“E-waste smuggled into the country leaves a trail of pollution”, Malaysiakini, October 17, 2022).

In December 2022, over 20 tonnes of illegally imported e-waste was discovered in Penang which was then sent back to its country of origin – the US (“20 tonnes of e-waste found in Penang to be returned to US”, Free Malaysia Today, December 8, 2022).

Formal e-waste facilities are expensive and challenging to build in developing countries since they require advanced technology. As such, informal and illegal processing of e-waste has been an increasingly flourishing sector.

Illegal e-waste is driven by the profits from extracting precious metals used in electric products such as gold, silver, and copper.

Malaysiakini reports over 200 illegal e-waste recycling facilities in Malaysia in areas such as Segamat (Johor), Gurun (Kedah), and Teluk Penglima Garang (Selangor) and over RM10 billion lost in tax revenue, in addition to the environmental degradation and health impact.

In 2018, “plants paid between RM3,000 to RM6,000 per [e-waste] container. Today, they pay RM6,000 per 20-foot container and up to RM10,000 for a 40-foot container”. The recent gold price increases is only expected to exacerbate illegal e-waste processing.

e-Waste Regulations in Malaysia

Only licensed facilities are authorised to treat e-waste in Malaysia. The DOE has licensed 35 companies to treat/manage and 121 collection centres to gather e-waste. In 2021, 2,459 tonnes of e-waste were collected.

Industries generating e-waste are bound by legal frameworks to report their generation and disposal of e-waste on the online portal eSWIS (Electronic Scheduled Waste Information System).

However, household e-waste is more voluntary-based with no regulating guidelines making tracking, recovery, and calculating material recovery difficult.

The new proposed regulation “The Environmental Quality (Household Scheduled Waste) Regulation” aims to rectify this. Informal parties offer monetary incentives to the public in exchange for their e-waste. However, the regulation, if implemented, forbids all stakeholders from selling their e-waste to non-DOE authorised parties.

Some initiatives have been taken to collect household e-waste.

In 2015, the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC), the Malaysian Technical and Standards Forum Bhd and industry players organised the “Mobile E-Waste: Old Phone, New Life” initiative. Collection boxes collecting small electronics not in use (such as mobile phones, tablets, hard disks, iPods, MP3 players, power banks) were placed near telecommunication companies, school/universities, shops, and offices. From June 2015 to March 2018, over 2 tonnes of e-waste was collected.

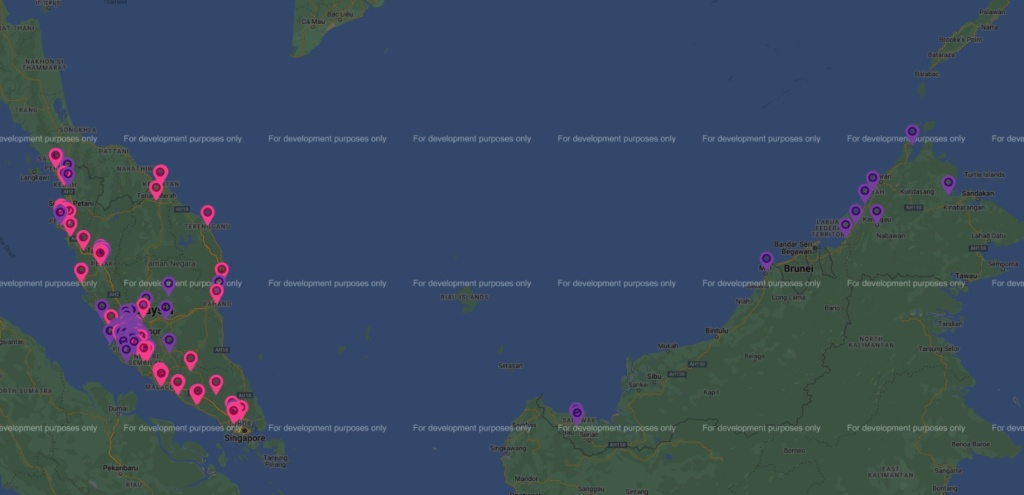

Furthermore, numerous collection centres and collection points have been put to gather e-waste. However, they’re concentrated in the urban areas of West Malaysia (see Figure 1 taken from E-waste management in Malaysia website).

Figure 1

Source: https://ewaste.doe.gov.my/index.php/about/list-of-collectors

Lack of proper household e-waste management frameworks lead to e-waste being discarded with other household waste. This increases the burden on municipal solid waste management system (“Discovering opportunities to meet the challenges of an effective waste electrical and electronic equipment recycling system in Malaysia”, Ismail & Hanafiah, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 238, 2019).

Lack of Awareness amongst Malaysians

Awareness and education dissemination towards e-waste is still lacking.

A survey found that 43% of respondents in Shah Alam didn’t know what e-waste was and majority of respondents weren’t aware of any proper disposal channels for electronics. Furthermore, most of the MCMC and DOE programmes target the urban population.

The MyEwaste app used to find nearby registered collection centres has been downloaded a mere 449 times (as of May 2021). This indicates how only a very small proportion of the public are aware.

As a result, only 5% of consumers dispose e-waste properly (sending for recycling or returning to the manufacturer) whereas 57% throw these along with other waste or keep in storage.

Imposing fines on illegal recycling has proven to be ineffective in other countries since the workers are poor and are desperate for income (“E-waste: a problem or an opportunity? Review of issues, challenges, and solutions in Asian countries”, Herat & Agamuthu, Waste Management & Research, Vol. 30, Issue 11, 2012).

The government has tried licensing illegal recyclers. However, the success of such a scheme depends on the responsibility of consumers to not sell e-waste to informal recyclers and only dispose to formal collection centres. This responsibility can only be conveyed through proper public awareness on e-waste.

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR)

The EPR is a powerful initiative, recommended by the Basel Convention of which Malaysia is a signatory – to improve e-waste management.

The EPR posits that producers and importers of electronic goods should share the responsibility of collection and treatment of these goods. The EPR also advocates that producers should make products that last longer alongside using materials that are sourced, handled, and recycled effectively and have take-back schemes.

The EPR has been successfully implemented in numerous developed countries.

Japan implemented the e-waste take-back scheme in 2002 wherein consumers pay a mandatory e-waste collection and recycling fees upon purchase. As a result, the majority of e-waste in Japan is recycled.

We’re working on implementing the EPR framework (“Strategies to manage electronic waste approaches: an overview in Malaysia”, Al-Rahmi et al., International Journal of Engineering and Technology, Vol. 7, Issue 4, 2018). Sellers will send the disposal fees paid to the DOE which will then redistribute them to collection and recovery centres in the form of subsidies.

The Circular Economy of e-Waste

Unfortunately, most efforts towards e-waste recycling focuses on maximising profits by solely extracting precious metals.

This means foregoing dismantling other less valuable but harmful materials. Separating and recovering more materials require additional extraction steps and costs.

The non-metallic fractions (NMFs) and plastics which account for majority of the e-waste are either incinerated or landfilled.

These NMFs and plastics contain numerous toxins, brominated flame retardants, heavy metals and other hazardous substances which require proper separation and safe disposal (“E-waste in the international context – A review of trade flows, regulations, hazards, waste management strategies and technologies for value recovery”, Ilankoon et al., Waste Management, Vol. 82, 2018).

Given the increasing depletion of non-renewable raw materials used in electronic manufacturing as well as increased prices, e-waste should be regarded as a critical “source of secondary raw materials.” One million mobile phones generate 24kg of gold, 250kg of silver, 9kg of palladium, and 9000kg of copper.

In 2019, 39 million tonnes of metal was used to meet the production demand for new electronics. Also, if all the e-waste generated in 2019 was collected and recycled, 25 million tonnes of secondary metals worth USD57 billion could have been derived.

Although this leaves a 14 million tonne gap of needing primary extracted raw materials, it’s still imperative to utilise all possible secondary raw material before resorting to extracting more primary raw materials.

Hence, it’s essential to improve e-waste collection and processing so that secondary raw materials can re-enter the manufacturing process and decrease straining natural resources and the environment as a whole.

Scaling up recycling could also lead to millions of new jobs globally (“The Growing Environmental Risks of E-Waste”, Geneva Environment Network, January 16, 2023).

Hence, EMIR Research recommends:

- Developing more facilities for e-waste processing equipped with advanced technology and safety measures;

- Invest in R&D for technology to treat and manage e-waste. Apple developed an e-waste robot called Daisy – which dis-assembles 200 iPhones per hour and 1.2 million iPhones annually. Such technology would increase the volume of recycled e-waste and prevent individuals from coming into close contact with toxic materials;

- Incentivise foreign companies experienced in advanced e-waste recycling technology to transfer their know-how to Malaysia;

- Ensure that all e-waste recycling focuses on maximum recovery of resources such as separating plastic fractions and NMFs also;

- Improve awareness among consumers regarding the environmental hazards of e-waste and their responsibility to recycle;

- Implement household e-waste legislation and framework wherein households are liable to dispose their e-waste to registered collection centres only;

- Increase e-waste collection centres in less urbanised states;

- Ensure that the EPR is implemented (as per the Basel Convention); and

- Expand the definition of e-waste to include a more holistic list of electronics (based on the EU classification as mentioned in Table 1) to educate and encourage consumers on what electronics they can recycle.

Jason Loh and Juhi Todi are part of the research team at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.