Published by BusinessToday & AstroAwani, image by BusinessToday.

When it comes to the Malaysian labour market, it is evident that we’re experiencing a significant imbalance. We are losing high-skilled talent en masse yet transfusing ourselves with low-skilled foreign workers.

Over the years, Malaysia’s reliance on foreign workers in the 3D sector has grown exponentially to the point that we now have around 2.1 million documented foreign workers, as of February 2024.

The Ministry of Economy had previously set the ceiling for the number of foreign workers at 15% of our total workforce. This ceiling was expected to be reached by May of this year based on the current rate of approval process.

The Malaysian government has made efforts to reduce our reliance on foreign workers. In 2016, the then government implemented a policy that compelled the manufacturing sector to ensure its workforce comprised 80% of the local workforce and a maximum of 20% foreign workforce. However, the deadline for compliance was subsequently extended to the end of 2024.

In March of 2023, the MADANI government imposed a hiring freeze on foreign workers, which has seen the deadline extended this year.

These policies aimed to reduce reliance on foreign workers, with the former gradually decreasing their numbers and the latter completely halting the hiring process.

However, many employers across sectors have deemed these policies impractical. The goal of achieving an 80% local workforce quota by the end of 2024 was said to be unreachable, with some employers citing potential workforce shortages as their reason for wanting the hiring freeze to be lifted.

The Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers even stated that they prefer to hire local workers, but there is an insufficient supply of them.

However, perplexingly, despite the reported shortage in the local workforce, the unemployment rate stood at 10.6% among youths aged 15 to 24 and 6.6% among 15 to 30-year-olds,[DP1] as of February 2024.

This apparent contradiction can be explained by the fact that many individuals in this demographic may not be interested in the available job opportunities.

As a result, the existing policies may not offer a definitive solution to the problem; instead, they may serve as a patchy remedy for a multifaceted issue.

Foreign workers in Malaysia typically take up jobs that locals often deem undesirable, such as those in construction, manufacturing, and cleaning services, which are commonly referred to as the 3D sectors (dirty, dangerous, and difficult).

The 3D sectors in Malaysia are widely considered unfavourable occupations. They, unfortunately, carry a significant social stigma and even often used as a negative example of what can happen if one does not prioritise education. The most common stigma associated with 3D sectors includes lower social status and low salaries.

After the initial influx of foreign workers in the 1990s, which helped solve labour shortages at the time, the number of foreign workers has continued to increase tremendously instead of being kept in check. This has added another layer of stigmatisation, where jobs in the 3D sectors are perceived as reserved only for foreigners from poorer countries, further diminishing their respectability among locals.

While 3D sectors are certainly not inherently associated with lower social status or less respectable, the low salary is indeed a big deterrent for Malaysians.

Over time, societal attitudes towards 3D sectors have improved, leading to increased willingness to work in these fields.

However, a notable caveat is that many Malaysians willing to take on these jobs have moved to other countries.

2016 report stated that 600,000 Malaysians were employed in 3D sectors in Singapore. Despite the salaries in Singapore’s 3D sectors being lower than those in its local high-skilled sector, when converted to Ringgit Malaysia (RM), these salaries even exceed those of some high-skilled workers in Malaysia at the time.

Given the significant depreciation of RM over the years, the situation has likely further deteriorated, potentially causing more workers to seek better salaries abroad.

However, the solution is not as simple as merely increasing salaries to an ideal level. Malaysia’s economy has been overly reliant on cheap foreign labour for far too long, and now we are grappling with the full extent of the negative consequences of this overreliance.

The initial influx of foreign workers brought a large number of cheap labour forces. As foreign workers are willing to work for lower salaries and in harsher conditions, the wages in 3D sectors have been depressed to a point where they are barely survivable for Malaysians.

While the implementation of minimum wage also affects foreign workers, one group that is exempted is illegal migrants.

We have 2.1 million documented foreign workers in Malaysia, making up approximately 13% of the Malaysian workforce. However, the total number of undocumented migrants throughout the country is uncertain, historically estimated to be at least equal to the documented figure (1:1 ratio).

The presence of illegal migrants has provided businesses with even cheaper labour options, allowing them to offer much lower salaries without incurring the costs of the increasingly expensive levy.

Furthermore, the age-old argument that increasing salaries would raise operational costs, putting more pressure on businesses and potentially resulting in higher costs for consumers, remains a significant concern.

These factors, combined with the continuous rise of youths’ interest in the gig economy, have exacerbated the perpetual cycle of needing even more foreign workers to fill these positions.

There is no single solution to this grim problem that could satisfy everyone, for this issue has been entrenched in our nation for decades. However, if we do not take decisive steps to finally address and reduce our reliance on foreign workers, the issue will only worsen.

Ironically, 3D sectors are exactly those that stand to benefit significantly from the proverbial 4IR-driven digital transformation, a goal Malaysia is striving to achieve. By implementing technologies such as robotics, automation, the Internet of Things (IoT), and augmented reality, these sectors can experience enhanced efficiency, safety, and productivity. These advancements not only benefit the specific industries but also create spillover effects across the broader economy! They can generate substantial demand for high-skilled labour, foster the emergence of new knowledge-intensive industries, stimulate local research and development, and finally attract high-value Foreign Direct Investments. Ultimately, local innovation and import substitution would finally thrive, reducing not only reliance on cheap foreign labour but on imported technologies—a significant departure from outdated “mid-80s solutions”.

Without such a demand for skilled labour (which is unlocked precisely through 3D sector transformation), initiatives aimed at “brain gain” and local upskilling programs are unlikely to succeed. The question arises: what purpose would there be in attracting back our most talented compatriots or upskilling and retraining the local workforce if the demand for their skills is lacking?

Although associated with significant initial investments, which the government must prioritise to overcome this hurdle for local businesses, the transformation of 3D sectors through 4IR creates substantial operating leverage for businesses of all sizes, thereby boosting profits and returns.

The agri-tech sector serves as a prime example of this phenomenon, and global investors are queuing to invest in it, recognising its lucrative potential. This might be pointing towards a serious knowledge gap or lack of awareness among the local businesses that policymakers will also need to address.

The overall strategy to address this nexus of issues must have a line running through it, and perhaps the imposition of a local workers quota is a bit premature.

As a primary step, policymakers should prioritize easing the financial burden on businesses to encourage investments in 4IR technologies. This can be achieved through various mechanisms such as government grants, soft loans, tax incentives, or accelerated depreciation schedules for 4IR-related assets, including staff training programs. These can be linked (in their magnitude) to the gradually increasing ratio of local to foreign workers.

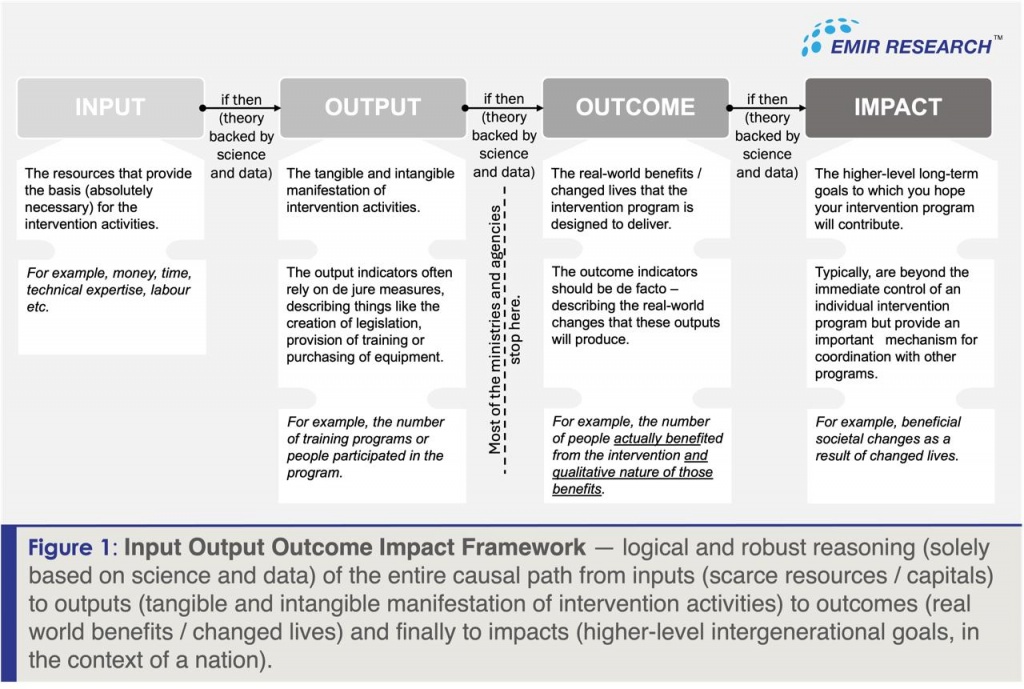

However, it’s crucial that all such initiatives are driven by a clear Input-Output-Outcome-Impact (IOOI) framework (Figure 1) as an important departure from the “speed-to-spend” focus (with no outcomes and impacts).

Furthermore, drawing from international experiences of countries addressing brain drain, establishing robust networks with expatriates (if not to return, then at least engage them on a very targeted project basis) is deemed one of the most effective strategies not only to address skills shortages but create channels for high-value foreign investment. This approach necessitates high levels of inter-ministry and inter-agency cooperation, for which the IOOI framework (Figure 1) is also helpful.

With these targeted avenues in place, the government is more apt to shift focus towards rebranding and rebalancing 3D sectors through comprehensive reforms involving local employers and workers within these sectors.

The government could design an apprenticeship-like programme for employers to participate in, enabling them to send eligible employees for upskilling, further training, or even enrolment in TVET to advance their careers. According to Zulkiflee, Puteh and Ahmad (2022), career development is the second biggest factor influencing Gen Y youths’ participation in 3D sectors, following job security.

This initiative must facilitate cooperation between ministries and industries, not only to identify the necessary skills but also to adsorb future TVET graduates into the workforce, creating a sustainable cycle of skilled workers generation.

Finally, EMIR Research would like to reiterate the need to relook into skill-focussed emigration (refer to “Unlocking opportunities: Streamlining immigration for Malaysian brain gain”) that aligns well with this overall effort.

The journey to reduce our reliance on foreign workers can be long and arduous, but it is the path we must pursue, as other nations already take advantage of 4IR-driven 3D transformation. And, therefore, without proper measures in place, not only will the population of foreign workers continue to grow, but we will also see more Malaysian leaving for greener pastures overseas.

Chia Chu Hang is a Research Assistant at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.