Published in Astro Awani, Business Today, Asia News Today, Focus Malaysia & The Stringer, image by Astro Awani.

Although Budget 2022 was inclusive of all segments of society, there is still some concern that the welfare system is not comprehensive and systematic enough.

On the one hand, unconditional cash handouts or transfers are never meant to be a permanent and structural feature for the recipients and serves only as a stop-gap measure to support households living within the broad parameters of the poverty line as well as those who have lost income and employment.

On the other hand, the government still needs to put in place a comprehensive and systematic welfare system that caters and meets the needs of all segments of society.

The issue then is not striking the balance between welfare and work.

But rather striking the appropriate and right balance between having a welfare system that is integral to our socio-economic safety net and ensuring that the recipients are not permanently dependent on it.

Having a Welfare State is not inimical to socio-economic progress and productivity. As it is, welfare aid helps, e.g., the unemployed or disabled, make ends meet while transitioning to employment.

The key is to also have in place mechanisms that ensure and disincentivise recipients from being overly dependent on the additional source of cash from the government – so that e.g., the dependency becomes long-term (no longer temporary) or inter-generational (i.e., from parent to children when they reach adulthood).

In attempting to capture all intended target recipients and hence becoming more comprehensive, a welfare system should be adequately flexible and adaptable to the contextual dynamics and exigencies of the situation.

So, as a system, welfare is not meant to be in-built in relation to the beneficiaries, that is (to be distinguished from the aid or benefits) – so that reliance becomes an absolute entitlement. And likewise, a welfare system should not be rigid so that it becomes exclusive, thus undermining its purpose.

Currently, we have a situation where the Middle 40% (M40) category remains vulnerable in meeting their household living expenses and paying off loans. Like the bottom 40% (B40) category, many are also experiencing a drastic reduction of income due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Even though M40 households received a total of RM250 from the one-off Special Covid-19 Aid (BKC) under the National People’s Well-Being and Economic Recovery Package (Pemulih) in recent months, the amount is simply inadequate to cover for emergencies and essential needs.

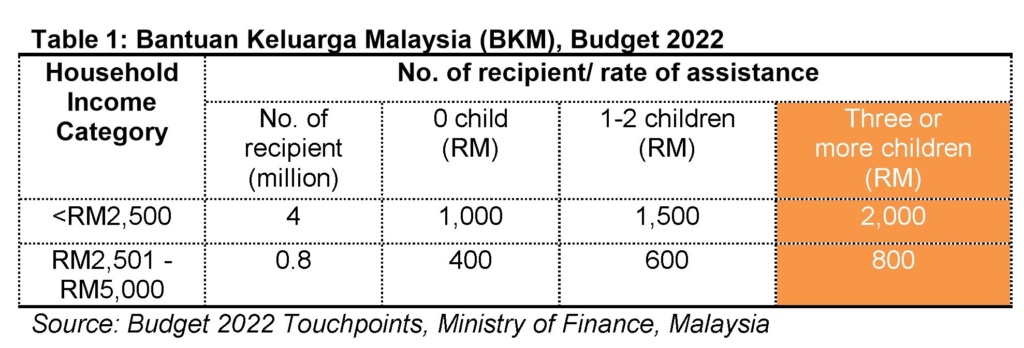

And although the government is committed to increasing the cash assistance to the B40 in Budget 2022, the amount provided under Bantuan Keluarga Malaysia (BKM) will not be enough for them to make ends meet (Table 1).

Table 1: Bantuan Keluarga Malaysia (BKM), Budget 2022

Source: Budget 2022 Touchpoints, Ministry of Finance, Malaysia

For instance, when calculating the amount of assistance received per month, households earning less than RM2,500 per month with three children still do not have much disposable money on hand.

Assuming the parents have three children, each family member only has RM33 additional assistance per month to survive (i.e., RM2,000 divided by 12 months divided by five family members).

It is even worse for the households earning between RM2,501 and RM5,000 per month.

With the same assumption that the parents have three children, each family member only has RM13 extra cash per month to cope with the living expenses (i.e., RM800 divided by 12 months divided by 5 family members).

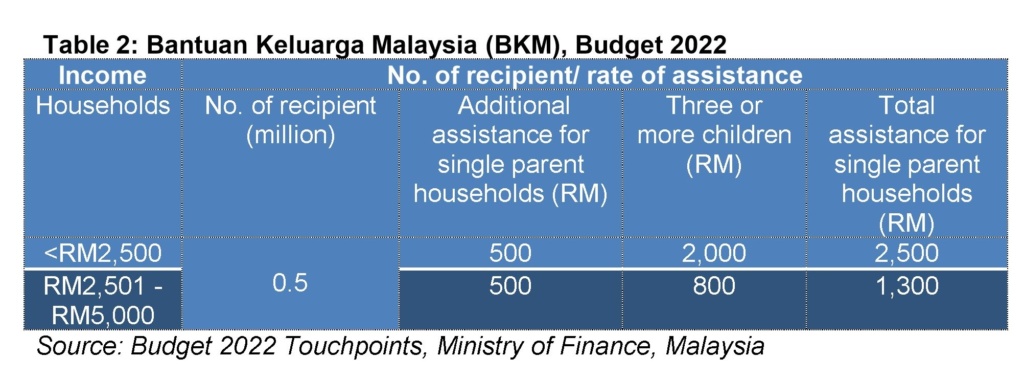

In addition, the total assistance given to single parent households might not sufficient to cover expenses for daily needs.

Such a scenario is especially pertinent if single parents suddenly become unemployed due to an accident or saddled with high medical expenses, among others.

As for single parent households earning less than RM2,500 per month with three or more children (Table 2) which entitles them to receive a total of RM2,500 (i.e., RM2,000 plus RM500), each family member only receives RM52 per month (i.e., RM2,500 divided by 12 months divided by 4 family members).

Table 2: Bantuan Keluarga Malaysia (BKM), Budget 2022

Source: Budget 2022 Touchpoints, Ministry of Finance, Malaysia

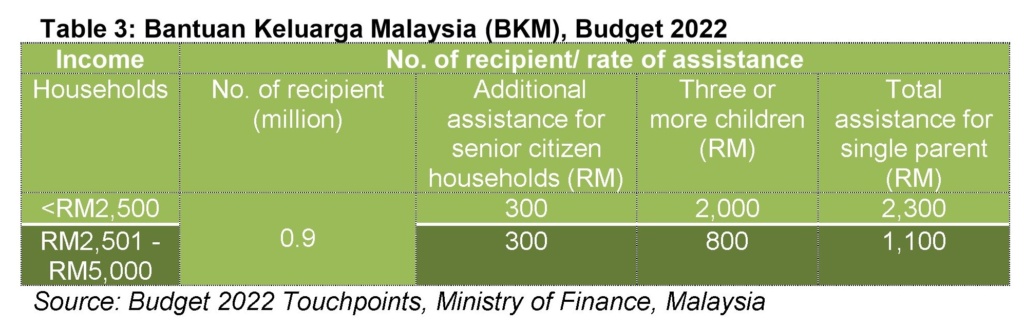

Although the government has also targeted welfare among senior citizen households by providing additional assistance of RM300 for those earning less than RM2,500 per month with three or more children (Table 3), each family member only receives RM38 per month (i.e., RM2,300 divided by 12 months divided by 5 family members).

Table 3: Bantuan Keluarga Malaysia (BKM), Budget 2022

Source: Budget 2022 Touchpoints, Ministry of Finance, Malaysia

Set against the backdrop of both supply-side shocks resulting in and taking place in tandem with demand constraints at the onset of the crisis with the imposition of the lockdowns, many lower-income households have had to take on more debt by e.g., pawning their jewellery and prized possessions just to meet some of their daily expenses or for emergency needs.

Recall that the economic contraction from the supply-chain disruptions and restrictions also saw some food prices (as a daily necessity) sky-rocketing – which only added to financial woes of the lower income groups.

This included basic items such as cabbage which increased to RM6.50 (representing a whopping 62.5 per cent increase) and cucumber which increased (by 300 per cent) from RM1 to RM3 by late April last year.

Back then, the Malaysian Institute of Economic Research (MIER) had projected that household income would fall by 12 per cent relative to the baseline, which amounts to a total income loss of about RM95 billion. Such a fall would be manifested in a sharp decline in consumer spending by 11 per cent, despite the drop in general consumer price level by 4.4 per cent.

More than a year on, many still haven’t recovered from the impact of the economic shock on their purchasing power.

According to Fitch Solutions, total consumer spending fell by 5.4 per cent to RM855 billion over 2021 from RM905 billion in (pre-Covid) 2019. Recovery is expected to only pick up in 2022.

Sluggish consumer spending reflects weaker purchasing power and for the lower income groups, this will take a longer time to recover.

There is, therefore, an increasing concern that the same recipient households as referred to above will still fall into an even lower income category particularly if they are not able to recover from the income and job losses arising from the prolonged and on-going impact of Covid-19.

Hence, our welfare system should take into consideration the scarring impact of the lockdowns on the lower income households and even those who in the lower M40 sub-category.

Both the upper B40 and lower M40 would also be highly indebted in the context of the banking system – where our household debt surged to 93.2 per cent of the gross domestic product (GDP) as of December 2020.

Household debt declined to 89.6 per cent in the first half of 2021 but stands at RM1.34 trillion.

Worryingly, household borrowings expanded by 41.6% this year despite weaker purchasing power outlook and pessimistic business sentiment (e.g., as highlighted in the FMM (Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers)-MIER Business Conditions Survey 1H2021 – which is expected to continue well into 2H2021).

This could mean that instead of borrowing on the back of buoyant income levels, many are mainly borrowing just to maintain their living standards amidst higher cost of living.

In conclusion, we need a welfare system that is more comprehensive and systematic so as to be more inclusive.

And it should be able to (temporarily) adjust the level and amount of cash handouts to reflect the broader economic backdrop/reality.

Jason Loh and Amanda Yeo are part of the research team of EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.