Global violent extremism and terrorism (VE&T) evolve faster than most countermeasures can cope. Malaysia’s Action Plan on Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism (MyPCVE) aims to strengthen national resilience but, though it outlines core objectives, may lack the structures for rapid coordination, iterative learning, and agile responses—all crucial against fast-changing threats.

To address these gaps, Malaysia should adopt the centre-out approach—a proven governance model in high-uncertainty fields like corporate innovation, crisis response, and military operations (Kim & Spear, 2013). Instead of rigid, top-down orders, centre-out relies on dynamic decision-making across multiple layers. While this can significantly enhance P/CVE outcomes, its principles are equally applicable in areas like disaster preparedness and healthcare, ensuring Malaysia is better equipped for complex challenges.

MyPCVE itself acknowledges inadequate inter-agency coordination in its situational analysis (p. 25). Yet, as EMIR Research has notedin “From Checklists to Impact: Strengthening MyPCVE with Evidence & Expertise”, the plan’s design does not systematically address this shortfall. Failures in coordination can be catastrophic: for example, Sri Lankan authorities had warnings before the 2019 Easter bombings but did not share them effectively, resulting in a preventable tragedy (foreignpolicy.com). Such lapses expose critical shortcomings in any fragmented, “business-as-usual” approach. To avoid redundancies, inefficiencies, and security gaps, Malaysia’s P/CVE strategy urgently needs an integrated governance model.

The centre-out approach offers a robust alternative, redefining how national strategies can be orchestrated. Rather than a top-down hierarchy issuing blanket directives, the “centre” (a lead agency or coordinating council) functions as an enabler and knowledge hub. It provides core resources, standardised guidelines, and best practices to “outer rings”—local authorities, communities, and partner agencies—while empowering them to tailor solutions and innovate based on local contexts.

Importantly, unlike a laissez-faire model, centre-out ensures a constant feedback loop. Field-level stakeholders share real-time data, experiences, and lessons back to the centre. Policies and standards are then refined and re-diffused, forming a virtuous cycle of experimentation, integration, and sustained learning.

Key elements and mechanisms of the centre-out approach include the following:

- Strong Central Coordination – A designated authority or leadership hub orchestrates overarching strategies, aligning objectives, resources, and execution across the entire system.

- Empowered Peripheral Actors – Local units, departments, or community partners maintain meaningful autonomy to adapt guidelines and policies to their specific conditions, ensuring more responsive and context-aware implementation. However, it is important to note that autonomy must always be supported by the professional expertise of peripheral actors and the robustness of established standards. Only when research-driven standards are in place can peripheral stakeholders accurately determine what works and what does not—where a more experimental approach, based on local idiosyncrasies, may be needed.

- Dedicated Central Depository – A robust repository (physical or digital) compiles data, research, operational results, and emerging best practices in one accessible hub, giving all stakeholders a shared reference point for the latest evidence-based insights.

- Institutionalised Research & Standardisation – Expert-led panels or specialised teams systematically evaluate field inputs, develop standard operating procedures (SOPs), refine professional standards, and design training curricula grounded in solid evidence.

- Continuous Feedback Loops – Lessons, success stories, and shortfalls from the field flow back to the centre, where they are synthesised and disseminated system-wide, enabling real-time updates to policies, SOPs, and strategic planning.

These key elements make it clear the centre-out governance model naturally integrates the Input-Output-Outcome-Impact (IOOI) framework, professionalisation, standardisation, and research rigour—elements MyPCVE currently overlooks, per “From Checklists to Impact: Strengthening MyPCVE with Evidence & Expertise.” In Scandinavian countries, for instance, well-coordinated multi-agency frameworks following centre-out mechanisms have been the norm. Police, schools, and social services share information under a national strategy, ensuring early prevention is truly collaborative (nordforsk.org).

Yet MyPCVE risks reproducing old inefficiencies because it involves sheer numbers of initiatives and dozens of government bodies without establishing clear mechanisms to orchestrate such large, interconnected networks. Proposals for inter-agency collaboration, such as case-reporting platforms, the Tele-MyPCVE hotline (1.5), a shared VE&T database (1.7), and a digital MyPCVE repository (4.7), are commendable but limited in scope and clarity, potentially limiting critical information exchange with peripheral stakeholders. Access rules beyond government agencies are vague, and there is no designated authority to ensure these platforms are used effectively. Meetings among ministries (1.8), dialogues with CSOs (1.6), and discussion programmes (4.21) are planned but lack concrete agendas, and it remains unclear how resolutions will translate into real action.

Likewise, the plan omits a clear hierarchy or central leadership structure, leaving it uncertain whether a central coordinating task force or committee will oversee MyPCVE beyond the ad-hoc committees assigned to specific tasks. Only Initiative 3.6 suggests a special committee for deradicalisation. However, its role in the broader rehabilitation and reintegration framework—such as the multi-agency reintegration programme (3.7) and strategic employment partnerships for ex-detainees (3.10)—remains undefined, raising concerns about stakeholder interoperability. Additionally, the absence of transparent appointment processes raises concerns about whether multi-disciplinary expertise—and the leadership capacity it brings—will be integrated.

Adopting centre-out principles, which naturally demand IOOI institutionalisation, professionalisation, standardisation, and robust research, would make Malaysia’s P/CVE strategy more cohesive, adaptive, and impact-driven. Inter-agency cooperation would benefit the centre-out mode, ensuring an authoritative but flexible coordinating body that shares real-time intelligence with ministries, state authorities, and front liners. It also standardises and professionalises Malaysia’s P/CVE initiatives by employing evidence-based guidelines and consistent training modules, adhering to the IOOI framework. Ongoing workshops and drills would foster trust, efficiency, and a culture of continuous learning (including tacit knowledge) across sectors, complementing the central knowledge hub mechanism.

The centre-out approach also supports an end-to-end feedback loop: a dedicated research consortium, nested in the central coordinating body, can monitor VE&T trends and refine strategies, updating stakeholders promptly. This ensures the national response stays ahead of extremist tactics rather than reacting too late.

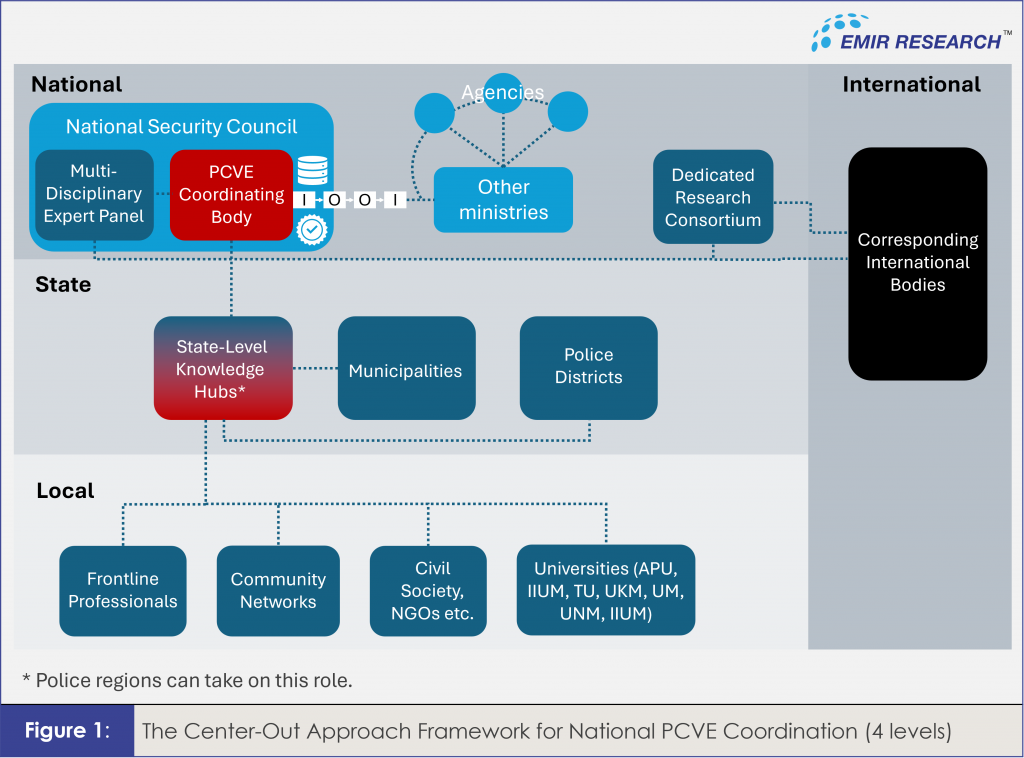

Ultimately, the centre-out model transforms the P/CVE environment into a unified learning ecosystem—one capable of adjusting faster than extremists can adapt. Figure 1 below suggests how this model could be structured in Malaysia’s context, illustrating the interactions between a central coordinating body and its peripheral actors within a dynamic, integrated governance network.

Crucially, this dynamic, high-velocity governance paradigm need not stop at counter-extremism. Many complex and fast-moving policy areas–from disaster response to public health and education–face similar coordination and adaptability challenges. By successfully integrating centre-out features in P/CVE, Malaysia can create a template to apply in other sectors!

Malaysia stands at a crossroads both in its fight against violent extremism and its pursuit of efficient governance. The analysis above makes it clear that centre-out is the missing link in Malaysia’s P/CVE strategy, transforming it from a fragmented “checklist” of initiatives into a living, learning system capable of outpacing the evolving threat. By prioritising this shift, policymakers would not only bolster national security through better coordination, standardisation, and adaptability in counter-extremism, but also create a replicable blueprint for tackling other governance challenges.

Dr Margarita Peredaryenko and Avyce Heng are part of the research team at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.