Published by AstroAwani, image by AstroAwani.

Brain drain has long been a persistent issue in Malaysia, studied repeatedly even before the twenty-first century. According to Koh (2012), by the year 2000, the emigration rate of Malaysians with tertiary education stood at 10.5, significantly surpassing the world average of 6.1 for upper-middle-income countries at that time.

Global data indicates a substantial increase in the Malaysian skilled diaspora aged 25 years and above. The numbers have risen from about 125,000 in 1990 to around 200,000 in 2000, further increasing to approximately 300,000 in 2010, and reaching about 500,000 in 2020, reflecting exponential growth (referenced in “Malaysian Brain Drain – Don’t Go Chasing Waterfalls”). If this trend continues unchecked, the loss of skilled labour may approach nearly 600,000 by 2025.

In the past decade, TalentCorp, an agency under the Ministry of Human Resources (MOHR) focusing on talent strategy, launched initiatives like the Returning Expert Programme (REP). However, these efforts have been largely unsuccessful in attracting highly skilled Malaysian diaspora back to the country. Only 5,774 applications were approved from 2011 to 2020, as per TalentCorp, while global data suggests we may have lost close to 200,000 highly skilled individuals over the same period.

One might wonder what has led to these programmes’ failure. Are the push and pull factors, as reported in “Malaysian brain drain – don’t go chasing waterfall”, so strong that any attempt to woo the Malaysian diaspora falters before it even begins?

In reality, Malaysian diaspora may long to return home. TalentCorp, citing a 2021 survey, reported that 92% of Malaysian diaspora expressed a desire to come home, yet they lacked a suitable platform to do so.

While TalentCorp has not specified the challenges faced by the diaspora, Jauhar et al. (2015) identified several factors that may have contributed, with the ease of immigration procedures being one of the key factors.

Another 2022 report mentioned that, based on the United Nations’ latest statistics, out of 1.86 million Malaysian diaspora, 1.05 million are women, and one of their primary reasons for not returning is related to discriminatory immigration laws, which impose additional difficulties and costs for women married to foreigners, especially those with children born overseas.

According to the Immigration Department, foreign spouses can apply for permanent residency (PR) in Malaysia, and later for Malaysian citizenship. However, the process is lengthy and complicated, leaving many foreign spouses unable to obtain PR status even decades after residing in Malaysia and applying.

The situation is particularly challenging for Malaysian women married to foreigners because the Malaysian Federal Constitution does not recognise children born overseas to Malaysian mothers as Malaysian citizens.

Therefore, when the Ministry of Home Affairs (MOHA) announced that there would be an amendment to the Federal Constitution granting Malaysian citizenship to children born overseas to Malaysian mothers, it was warmly welcomed.

However, as we all know, the change came bundled with other amendments considered detrimental to the welfare of stateless children. It also includes a clause that bars children of permanent residents from being registered as Malaysian citizens (a practice currently allowed). Furthermore, these changes are not retroactive, affecting only those who may migrate in the future.

Apart from the complicated process of obtaining PR, Malaysia’s stance on citizenship is another major concern for the Malaysian diaspora. Currently, Malaysia does not recognise dual citizenship, requiring individuals to renounce their Malaysian citizenship upon obtaining citizenship in another country.

In the report highlighting immigration-related issues as one of the major hurdles to returning to Malaysia, an interviewee residing in the United Kingdom also mentioned that she would not return due to citizenship issues affecting her children.

Not having a PR for foreign spouses creates issues, potentially making them ineligible for employment, despite the Immigration Department allowing foreign spouses under the Long-Term Social Visit Pass (LTSVP) to engage in any form of employment or business activities, provided they meet the requirements.

However, due to varying rules and regulations across different states, many foreign spouses without PR struggle with the system and end up unemployed in Malaysia, despite their potential to address severe brain drain and critical occupation shortages in the country. According to Family Frontiers’ survey in 2022, 75% of foreign spouses hold a Bachelor’s degree or higher education but remain unemployed due to the immigration system inefficiencies.

EMIR Research has emphasised and delineated effective brain gain programs in the earlier publication “Credible Malaysian Brain Drain Intervention is Long Overdue!”. One of the key recommendations is to shift the focus towards skilled immigration. This is not only aligned with global best practices (refer to “Migration and Brain Drain” policy recommendations by the World Bank) but has even been shown empirically, using Malaysian data, to be the winning strategy specifically for Malaysia – more effective and economically beneficial.

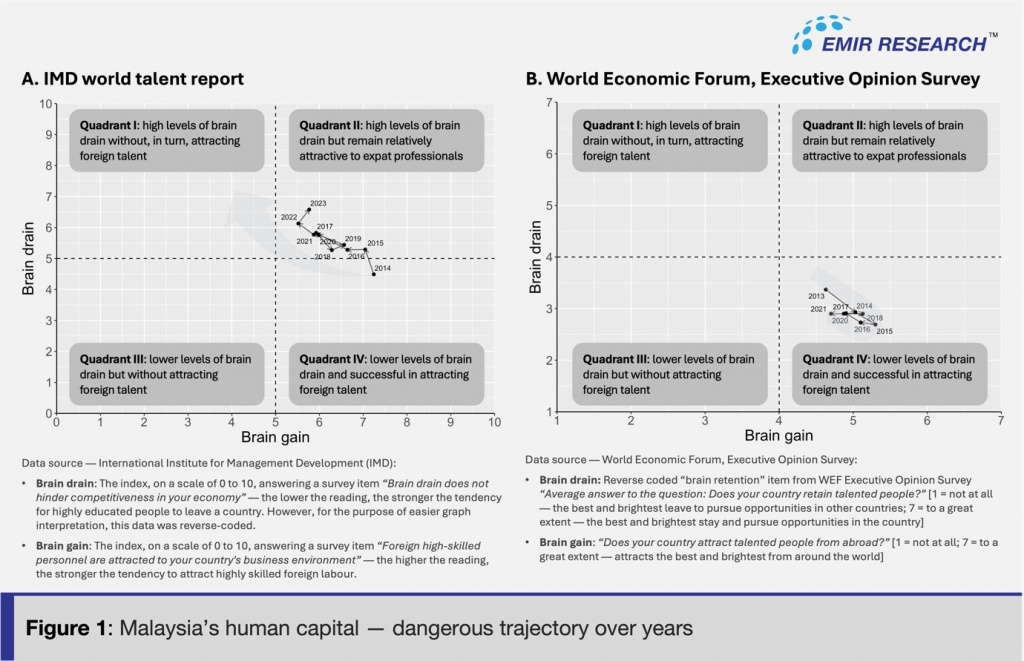

However, our convoluted immigration system has significantly hindered the Malaysian diaspora and their foreign spouses, reducing their motivation to return to Malaysia. This situation has greatly contributed to Malaysia’s increasing brain drain and growing lack of brain gain over the years, setting Malaysia on a dangerous trajectory (Figure 1).

If they can easily obtain a work permit, PR or even citizenship in their host country, where their spouse is a citizen, why would they choose to return home and deal with complexities for decades?

And if no one returns, we not only lose our treasured talented Malaysians but also miss out on potential valuable contributions from their foreign spouses.

One way to alleviate this situation is to factor in foreign spouses’ education and working experience in their home country when processing their applications.

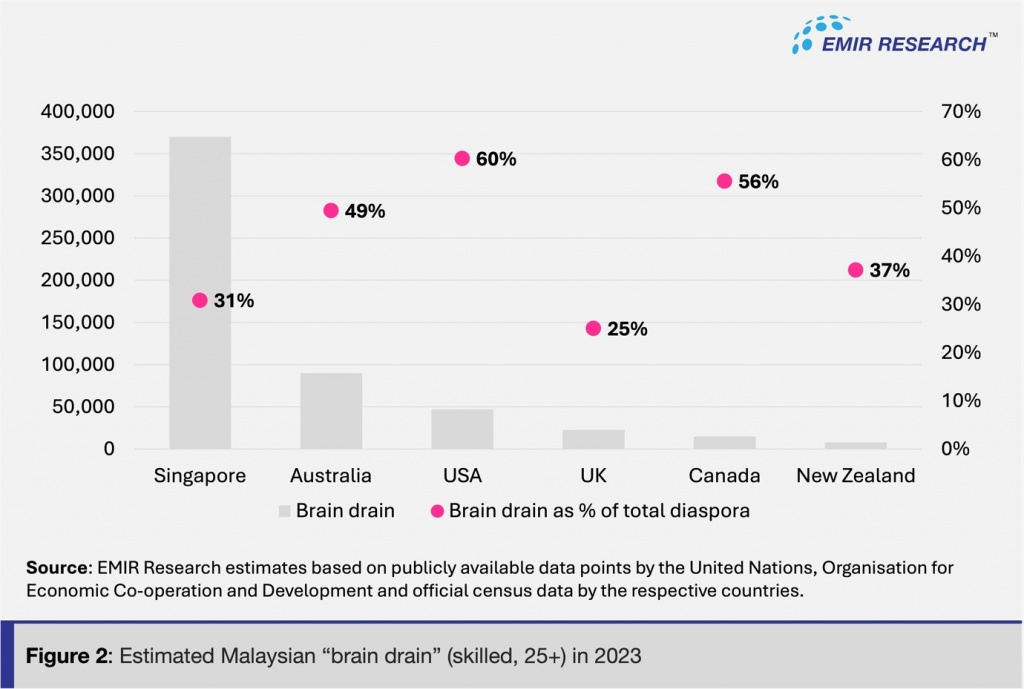

Many advanced nations have had skilled-focused migration policies for decades, prioritising individuals with specific skills and qualifications deemed valuable to the receiving country’s economy, workforce, or society. Notably, most of these countries are also the largest recipients of our brainiest compatriots (Figure 2).

For example, the Australian government has been offering skill-based migration and work visas for people in specific occupations. Eligible applicants can register for these visas, which, once granted, provide permanent residency in Australia without employment restrictions (including not being bound to a specific employer).

Similarly, the Canadian and New Zealand governments have comparable policies. Canada’s Federal Skilled Worker Program allows individuals who have worked continuously in specified occupations for at least one year to apply for PR.

Meanwhile, New Zealand’s policy revolves around a point system that evaluates individuals based on their skills, work experience, qualifications, and job offers.

The government’s concern about “marriages of convenience,” where foreign workers marry locals solely to extend their stay or obtain PR, is valid.

However, it is precisely the implementation of effective skill-focussed migration policies, laws, and technology systems, with streamlined inter-ministry/government-agency cooperation that can help us not only identify the highly skilled and talented individuals needed in Malaysia but also exclude those who marry a local just to exploit the system.

The approach should involve combining and adapting spouse visas like LTSVP, Employment Pass, and PR, to identify foreign spouses with necessary qualifications and skills, providing them with a special pass for unrestricted employment, and potentially expediting their PR or citizenship applications. This eloquently demonstrates a prioritisation of high-skilled workers, potentially attracting more expatriates.

Additionally, we could reduce the continuous residency period required for PR registration for foreign spouses with critical qualifications. Currently, a foreign spouse must continuously reside in Malaysia under LTSVP for at least five years to be eligible to apply for an Entry Permit, which is required for PR registration.

Also, efficiency and competency in the Immigration and National Registration Departments must improve. There is simply no justification for dragging foreign spouses’ applications for over a decade with no progress. The applications must be processed promptly based on strict, transparent criteria, mirroring systems like New Zealand’s, where 80% of PR applications are processed within three weeks. New Zealand’s immigration services are also highly digitalised, leveraging technological advancements to automate processes and minimise the risk of system abuse and corruption.

Therefore, MOHA must identify and resolve the deep-seated issues within the two departments to improve efficiency.

Brain drain is a serious and complex phenomenon with no simple solution. However, an essential step toward addressing it is to stop wasting the time and valuable potential of skilled Malaysian diaspora who wish to return home with their foreign families by improving our immigration system for the betterment of our nation’s future.

Chia Chu Hang is a Research Assistant at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.