Published by AstroAwani, image by AstroAwani.

The moment a newborn takes their first breath is nothing short of miraculous. Yet, for millions of newborns worldwide, this moment is fraught with disparities that dictate the odds of survival. Despite advancements in medical technology and healthcare, millions of newborns continue to die each year globally, especially in low- and middle-income countries, with 2.3 million newborns dying within the first 20 days of life.

Neonatal mortality, defined as death after birth and within the first 28 days of life, remains a significant global health challenge. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019, neonatal disorders (40.7%) remained the leading cause of under-5 deaths in 2019.

However, here is the catch: although significant progress has been made in child survival rates, the decline in neonatal deaths has been notably slower. Startling statistics from 2022 alone reveal that nearly half (47%) of deaths among children under 5 occur during the newborn period (the first 28 days of life).

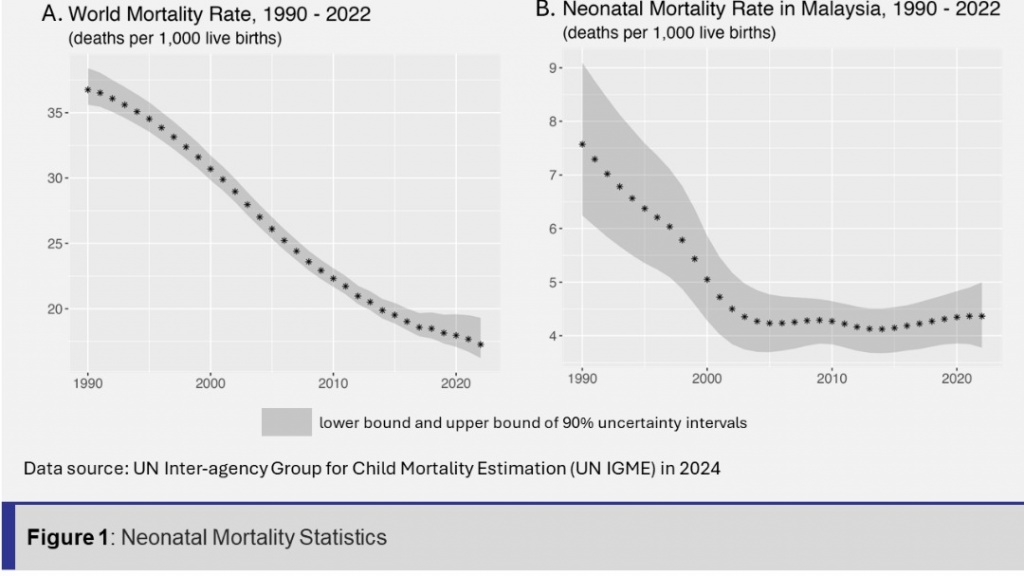

Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG3) targets healthy lives and well-being for all at all ages, specifically aiming to reduce neonatal mortality to at least 12 deaths per 1,000 live births. Despite global efforts, progress has started to plateau since 2010 globally, sparking concerns about meeting the SDG 3 target.

Interestingly, Malaysia witnessed a plateau in neonatal mortality about a decade earlier, with a slight but noticeable uptick since 2015 (Figure 1B).

While Malaysia currently exceeds the SDG target by a significant margin, striving for improved outcomes and long-term intergenerational impacts remains crucial. Proactive intervention to arrest any potential deterioration is paramount.

After all, the neonatal mortality rate is a key indicator of overall public health, reflecting strong correlations with medical factors, prenatal and postnatal care, as well as non-medical exogenous factors like nutrition, socioeconomic determinants, and culture.

Preterm births

Globally, prematurity ranks among the leading causes of death in children aged below five, a reality also evident in Malaysia. In 2020, the Malaysian National Neonatal Registry (MNNR) reported 10.7% preterm births out of 319,867 live births. The National Obstetric Registry reported that 6.6% of births in 2020 were preterm, with the highest rates observed among Orang Asli and Indian women, as well as women over 40 years old.

Preterm birth, especially before 37 weeks of gestation, is often associated with a markedly heightened risk of complications such as Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS) due to immature lung development. The presence of RDS escalates the risk of mortality among preterm infants.

Studies consistently identify prematurity as the most frequent cause of neonatal death. For instance, in a study, it was found that preterm-related complications account for 35% of neonatal deaths within the first week after birth.

Also, the Ministry of Health Malaysia revealed in 2022, the majority of preventable neonatal deaths (492 out of 735; 66.9%) occurred within the first week of life (refer to “Under-5 Mortality Review 2016: Looking into The Preventable Deaths”).

Alarmingly, the percentage of preterm births may be on the rise, largely attributed to ongoing shifts in societal lifestyles, the co-occurrence of preterm births and RDS, posing challenges to neonatal care and adding to the global burden of neonatal mortality. Factors such as rising obesity rates, largely sedentary lifestyles, delayed maternal age at conception, higher rates of chronic health conditions during pregnancies, and increased stress levels across societies are believed to contribute to the rise in pregnancy complications, including gestational hypertension and preterm births.

While sometimes unavoidable, preterm births can be prevented by minimising the risk factors associated with early delivery. Australia’s “Every Week Counts” program is a prime example, having successfully prevented about 4,000 preterm and early births since 2021. Malaysia could adopt a similar initiative, prioritising prenatal care and maternal education, and partnering with diverse stakeholders at the national level.

Moreover, in high-income nations, significant progress in neonatal care, including enhanced care for premature babies, has spurred the emergence of neonatology as a discrete medical sub-speciality and the establishment of neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). It’s crucial for relevant stakeholders to prioritise efforts to emulate these advancements and institute comprehensive, cutting-edge neonatal care across all healthcare settings.

Birth asphyxia

Shockingly, the World Health Organisation estimates 900,000 deaths each year due to asphyxia (a condition characterised by a baby having trouble breathing at birth), making it another significant contributor to early neonatal mortality.

Birth asphyxia can occur due to various reasons, such as compression of the umbilical cord, placental insufficiency, maternal hypertension, or complications during labour and delivery. This deprivation of oxygen can eventually lead to damage to the newborn’s vital organs, particularly the brain, heart, and lungs, ultimately resulting in death.

Birth or perinatal asphyxia commonly arises from complications during childbirth which result in systemic effects such as respiratory distress, pulmonary hypertension, and liver, myocardial, or renal dysfunction. Hypoxia, the basic pathology of neonatal asphyxia, may lead to complications affecting all organs/systems. According to the study “Very early complications of neonatal asphyxia”, the respiratory system is the most commonly affected (67%), followed by hypoglycemia (37.2%).

Birth asphyxia in newborn babies is a longstanding and, unfortunately, not uncommon issue, often resulting in the death of infants, especially those under 28 days old. For instance, in a 2018 childbirth case, a newborn baby died from shortness of breath (asphyxia) after his head became lodged in the mother’s perineum during a footling breech delivery, which then was classified as an avoidable infant mortality case.

Hence, it is time for the government to invest in expanding and improving emergency obstetric and neonatal care services, particularly in underserved areas. This entails developing comprehensive training programs for obstetricians, neonatologists, nurses, and midwives to enhance their proficiency in managing obstetric emergencies and providing neonatal resuscitation. Additionally, it is crucial to ensure that healthcare providers stay abreast of the latest global best evidence-based practices.

Addressing shortages of staff, particularly in NICUs, remains a pressing concern that demands immediate attention. Recently, it was revealed that one nurse attends three babies in the NICU, a ratio that falls way short of the recommended one-to-one care. Such understaffing seriously compromises the ability to promptly recognise and address the severity of the babies’ conditions, potentially leading to increased mortality rates. Therefore, urgent measures are needed to recruit and retain qualified healthcare professionals, including nurses and physicians, to mitigate staff shortages in NICUs.

Congenital anomalies

Congenital anomalies, also known as birth defects, comprise a wide range of structural or functional abnormalities that originate prenatally and are present at birth, as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These conditions may be diagnosed either before or at birth, or later in life.

Even as early deaths from other causes decline, the contribution of congenital anomalies to early mortality is increasing, highlighting a significant public health problem to be tackled.

According to the WHO estimates, 240,000 newborns die within the first 28 days of their life each year globally due to congenital disorders, representing another leading cause of infant mortality, causing a 20% mortality rate among children.

Congenital anomalies encompass a diverse range of conditions, including structural anomalies like cleft lip/palate, heart defects or neural tube defects, as well as chromosomal anomalies such as Trisomy 18 and Down syndrome. Additionally, functional abnormalities affecting organs, such as congenital heart disease, spina bifida and congenital diaphragmatic hernia, contribute to the complexity of congenital anomalies.

Prenatal diagnosis and screening are crucial to timely detection and management of congenital anomalies. Therefore, it is imperative to ensure universal access to comprehensive prenatal care services for all pregnant women, including prenatal screening and diagnostic tests for congenital anomalies.

Additionally, healthy maternal lifestyles are very important for the babies’ health. Therefore, enhancing maternal health services access is vital for promoting the well-being of newborns. This includes improving access to nutritional counseling and mental health support during pregnancy, especially for marginalised and underserved communities.

Ultimately, to effectively address neonatal mortality pathways, we need a holistic approach that encompasses medical interventions alongside credible efforts to address environmental, social, and governance factors.

It is also important to highlight that the recommendations outlined above consistently emphasize (nearly in every paragraph) the pressing need to attract foreign specialists and retain local talents, a critical endeavour given Malaysia’s well-documented challenge of healthcare worker brain drain. For further insights, refer to EMIR Research’s publication “Malaysia’s Healthcare Dilemma: Tackling the Issue of Brain Drain.”

These comprehensive measures not only directly contribute to giving every baby the chance to live a long and healthy life by improving overall maternal and infant health outcomes but also lay the foundation for a sustainable and equitable healthcare system!

Farah Natasya is a Research Assistant at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.