Published by AstroAwani, MYsinchew, TheStar & SinarDAILY, image by AstroAwani.

Asian stock markets and currencies continue to generally weaken at the back of risk appetite reduction in the context of murkier economic growth prospects in the region and the ongoing monetary policy tightening by the international central banks. However, Ringgit Malaysia appears to be the weakest in the Asian region (second weakest after the Japanese Yen).

Malaysia heavily relies on imports, including food items, which will ultimately increase the cost of living for Malaysians.

To address this issue, we need practical solutions that can quickly increase the demand for Ringgit Malaysia in both the short-term and medium-term.

On Thursday, 22 June 2023, the Bank of England and Norway’s Central Bank raised the bank rate by 50 basis points (bps) to 5% and 3.75%, respectively. Norway’s Central Bank also indicated its intention for another hike in August, predicting the rate would rise to 4.25% in autumn. At its meeting on that same date, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) raised its policy rate by 25 bps to 1.75%.

Although, on 14 June 2023, the Federal Reserve decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 5 to 5.25 per cent, most of the Federal Open Market Committee members indicated their expectations for at least another two rate hikes before the end of this year.

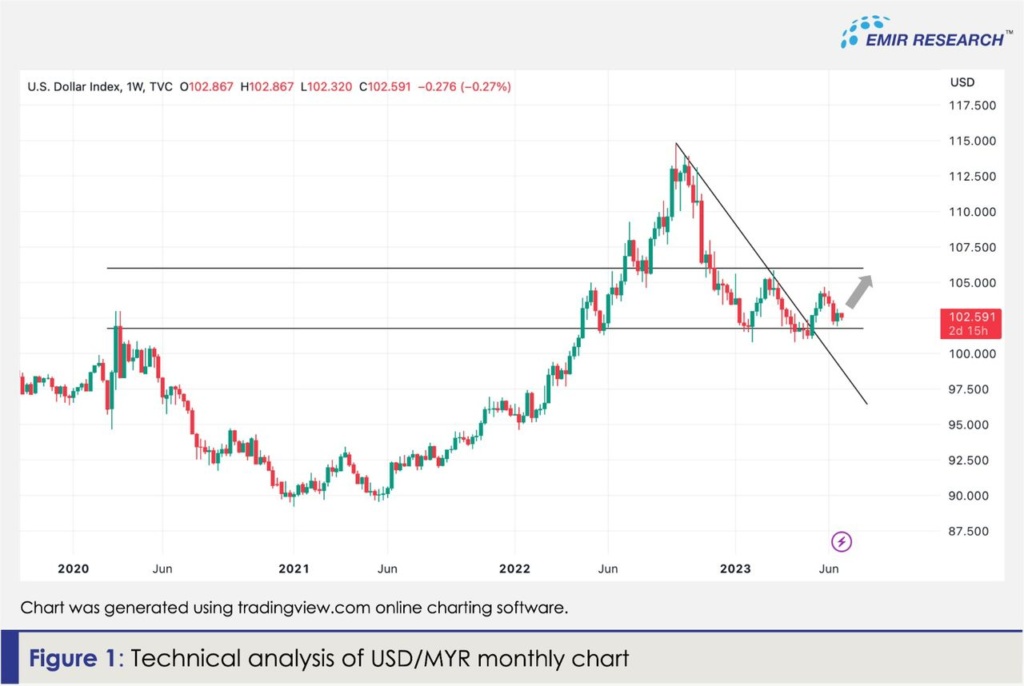

As evident from US Dollar (USD) Index weekly chart (Figure 1), USD local strengthening against the basket of global currencies remains a more likely scenario. The closest resistance level is at around 106, which, technically, leaves more room for the USD appreciation, making it more likely for Asian currencies to remain under pressure for some time.

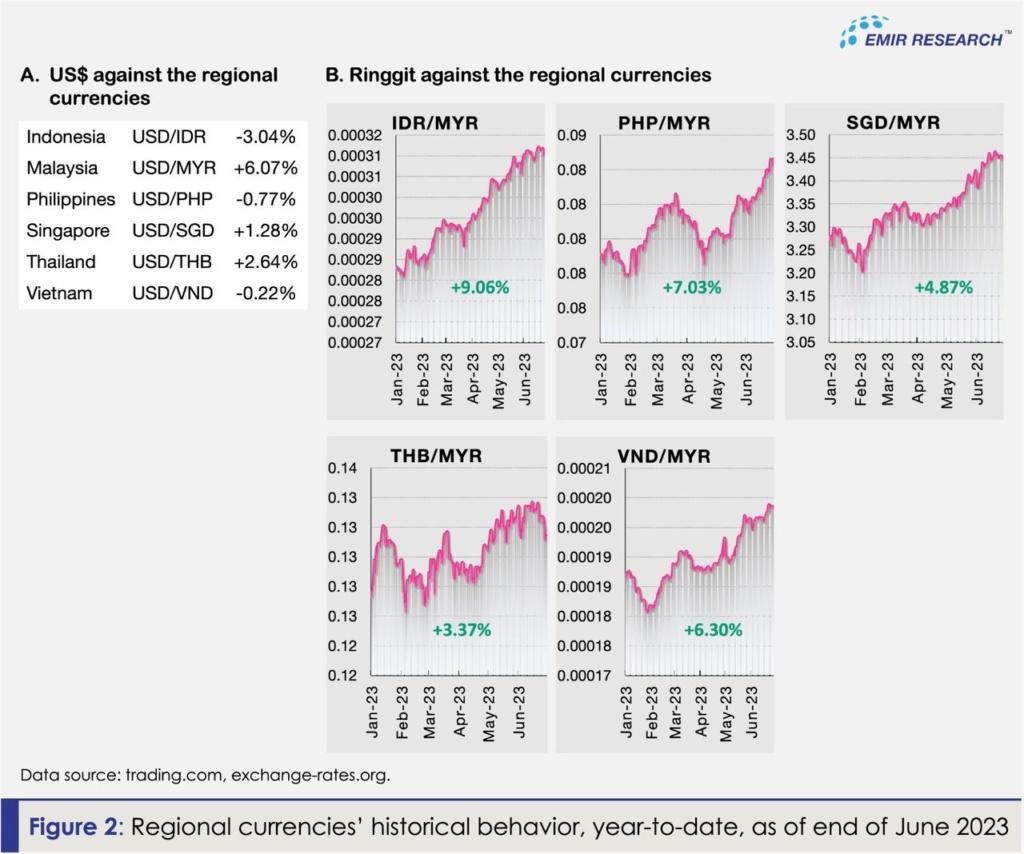

Even though all Asian currencies and markets have been taking a hit, Ringgit appears to be the weakest in the region (Figure 2). It not only had the highest depreciation against the USD among the regional currencies but also notably depreciated against the regional peers suggesting that even within the region, funds are flowing from Malaysia elsewhere in search of lesser political risk and common sense policies (given the common murkier economic growth outlook for the region).

On the monthly chart (Figure 3), USDMYR re-tested the 4.28 area — previously the resistance level formed by the wedge or flag chart pattern spotted by EMIR Research earlier (refer to “Malaysian Currency and Economy in a State of Constant Political Flux”) reaffirming it as a new support level.

Considering the current USDMYR surge as the fifth Elliot wave, the pair can reach at least 4.8 within the next few months. On the other side, noticing that USDMYR began to move in a new upward-looking channel (Figure 3), any downside move for the pair in the near term might be limited by the 4.4 level (support level).

To break this long-term trend something needs to change for Malaysia fundamentally —radical transparency, ethnic harmony, sound policies for a clear economic direction and moving Malaysia finally up the global value chain are good long-term goals.

However, in the meantime, the situation requires practical short- to medium-term measures to boost the demand for Ringgit and steam off its depreciation.

Using foreign reserves to buy Ringgit is not prudent and not sustainable, particularly when Malaysia’s reserves have shrunk significantly over recent years and are to be put to better use, among which to support vital imports if needed.

Raising OPR is not a solution either and, in fact, can worsen the Ringgit situation by hurting economic activities and worsening inflation. The funds are flowing from Malaysia due to its deep-seated structural issues (refer to “Malaysian Currency and Economy in a State of Constant Political Flux”) at a magnitude that no OPR hike can counter.

The recent historical performance of the Ringgit also shows how OPR hikes had minimal (if any) positive impact on Ringgit’s strength.

Therefore, alternative short-term to medium-term measures are needed.

For example, in the short term, policymakers should focus on seizing opportunities in the tourism and entertainment industry for international and domestic tourism, which will increase economic activity, thus lowering inflation and, eventually, strengthening Ringgit.

Tourism in Southeast Asia is well on the way to recovery. According to the UNWTO World Tourism Barometer tracker, Southeast Asia’s international arrivals reached about 70% of pre-pandemic levels in the first quarter of 2023. In addition, due to the current unrest in Europe, Asia shall become a more popular travel destination.

China has consistently led the top tourism spenders charts for years due to its growing middle class. However, India has recently emerged as another economy with a rapidly expanding middle class — one in every three citizens, according to People Research on India’s Consumer Economy.

In the situation of the weakening Ringgit right now, Malaysia must attract this sizable group of international travellers able to engage in discretionary consumption.

Therefore, the policymakers can consider introducing, for a period, visas on arrival for Chinese and Indian citizens (who fulfil specific criteria indicating their middle to high net worth) while also ensuring there are enough flights servicing Chinese and Indian markets which may require incentives to the Malaysian airline carriers.

Driven by the pandemic, adventure and sports tourism have been on the rise recently and is expected to surge even more in the coming years, which presents an excellent opportunity for Malaysia with its environment of biological diversity — untouched ancient forests, all sorts of beaches and picturesque mountains.

Therefore, policymakers should concentrate on creating adventure and sports tourism attractions, which can be done quickly and with minimal spending, and promoting them through local social media influencers with large international followings.

Maybe it is a perfect time also to revive the “Malaysia Truly Asia” campaign that was highly successful.

Perhaps, the policymakers need to be reminded how, at one time, Malaysia was one of the most popular destinations for medical tourism. This would require a heightened focus on resolving various long-standing problems in the medical industry.

Certainly, Malaysian policymakers could also learn from Singapore how to promote its entertainment industry to the whole of Asia – at the very least, they could learn how not to politicise international concerts and cultural festivals. There is a lot to ponder about why Coldplay will have a single show in Malaysia and six shows in Singapore while Taylor Swift is making Singapore the only stop in Southeast Asia for her upcoming tour. We can only imagine how much demand for Singapore Dollars is created through Singapore cementing its status as an Asian concert hub — Asia’s tour destination of choice for top stars.

However, it may be that it is still not too late for Malaysia to grasp at least an opportunity to promote itself as a regional travel hub for a seamless Umrah experience.

Thanks to Malaysia’s close bilateral relationship with Saudi Arabia, Malaysian Airlines have historically enjoyed one of the largest numbers of landing rights in Saudi Arabia.

Furthermore, Malaysia has a well-established network of Umrah facilitating agencies such as Tabung Haji and others. All they need to do is to extend their market to accommodate non-Malaysians also to take an opportunity to enjoy this Umrah facilitation. This will only expand the market for these agencies – more profit would come in, allowing these agencies to better cross-subsidise Malaysian Umrah travellers. And, in the short- to medium-term, this will create demand for Ringgit Malaysia, further strengthening it.

Apart from capitalising on the tourism industry, Malaysia should also take advantage of its status as a country that exports globally demanded commodities such as palm oil, rubber, oil and gas by demanding payments in Ringgit Malaysia. Therefore, countries importing from Malaysia will have to keep Ringgit Malaysia in their reserves, thus creating demand for it. Given the global de-dollarisation trend gaining traction (refer to “De-dollarisation—Elbowing USD in a Multipolar World”), such a move would be only welcomed now by many countries that already proactively diversify their foreign reserves baskets away from US Dollar.

Besides, Malaysia’s food security is another area that exerts tremendous downward pressure on Ringgit, given our growing dependency on food imports.

EMIR Research has emphasised multiple times how this situation can be turned around fairly quickly by utilising modern AgriTech (4IR), our vast unutilised waqf land, sovereign wealth funds and a large number of unemployed and undeployed (refer to “4IR enabled farmers: Solving national food security” and “Reinventing Malaysian Food Security Framework” in two parts).

This will not only reduce our food imports (downward pressure on Ringgit) but, provided there is a credible food security framework attached, will attract foreign investors. After all, the world’s most renowned sovereign wealth funds, such as the Government Pension Fund of Norway, Temasek, and Kuwait Investment Authority, invest heavily in their local AgriTech initiatives and similar initiatives worldwide. These savvy investors know that apart from a captive market AgriTech means efficiency and reduced risks with simultaneously increased yields.

In place of unwise foreign reserves spending or unthinkable OPR hikes, we can explore creative solutions and utilise our existing resources and opportunities to provide short-term support for Ringgit Malaysia.

Dr Rais Hussin is the president and chief executive officer of EMIR Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.