Published in AstroAwani & BusinessToday, image by AstroAwani.

Singapore is ranked second in the world in mathematics, science and reading while Malaysia is ranked 48th, 48th, and 57th, respectively (rankings obtained from the Programme for International Student Assessment by the OECD). Despite at one time being together under the umbrella of the federation, the contrast between Singapore and Malaysia’s education standard couldn’t be more striking as the former surges and leaping forward since Separation in 1965.

This is a wake-up call for Malaysia to examine the fundamentals of its education system and how it could produce high quality students and citizens.

Besides academic performance, personal development should also be one of the end goals of schooling. This is because children are at the peak of information absorption at such young ages, not just from books, but from their social interactions and environment.

Schools are a “sandbox” for children to learn and experience a scaled-down version of the real world. Every child’s engagement with their teacher, peer, or parent reinforces certain perspectives, predispositions, and attitudes. As these children eventually mature, enter society, and determine the future of the next generation, a nation’s fate quite literally rests on the quality of its schools.

Issues faced by Malaysian teachers

Though Malaysia has a good student-to-teacher ratio of 11.66, early quitting and dissatisfaction amongst teachers remain rife. A teacher’s job satisfaction directly affects the quality of their teaching and retention in a particular school. Multidimensional perspectives should be considered when addressing dissatisfaction amongst teachers.

According to a study by International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM), workload appears to be the most prevalent factor contributing to a teacher’s occupational stress (“Exploring Occupational Stress and the Likelihood of Turnover among Two Early Career Teachers”, International Journal of Advanced Research in Education and Society, Karim A. H., Vol. 4, Issue 3, 2022). As teachers assume the roles of lecturer, mediator, curriculum planner, exam grader, school administrator, and warden, it’s an understatement to say that they’re overloaded.

Moreover, the lack of resources, i.e., strong social networks, increases one’s vulnerability to negative cognition and emotions (“Socio-economic status of family as a factor of emotion regulation and well-being”, Singh S., Indian Journal of Health and Well-being, Vol. 4, Issue 8, 2013).

Without emotional regulation and a balanced lifestyle, any individual would become highly irritable, moody, and perform poorly in the long run. There has been an increasing amount of literature to support the link between poor emotional regulation and poor job satisfaction (“The emotion regulation roots of job satisfaction”, Madrid H., Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 11, 2020).

Hence, beyond ensuring workload balance for teachers, there should also be better support for maintaining employee mental health (see, EMIR Research’s article titled, “Investing in employee mental health in Malaysia”).

Another potential contributor to poor job satisfaction among Malaysian teachers could be the pay issue. For context, the starting salary for a government teacher is RM2,200 – just RM700 above Malaysia’s minimum wage. Only after eight years of working experience, the salary reaches RM3,600 (RM225 increase per year). In contrast, an entry-level banker immediately earns RM3,400 already.

Not to mention, the practical training or teaching practicum (as part of a graduation requirement for a teacher) is entirely non-salaried.

The benefits of increasing the salary increments for Malaysia’s public school teachers are twofold. Empirically, earnings are highly correlated with teachers’ education levels (“Quality of Malaysian teachers based on education and training: A benefit and earnings returns analysis using human capital theory”, Quality Assurance in Education, Ismail R., Vol. 25, No. 3, 2017). Therefore, improving teachers’ pay will attract more qualified graduates into the profession and double as an investment to enable existing teachers to upskill themselves locally or abroad.

Teachers perform an instrumental role in nurturing and developing the professionals and specialists of the future. However, some students under the pupillage of different teachers have significant performance differences (“Teacher Quality Malaysian Teacher Standard”, International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, Rahimi M.A., Vol. 12, Issue 7, 2022).

Hence, for a robust education system, Malaysia must first invest in nurturing high quality teachers to be model mentors in schools.

Issues faced by Malaysian students

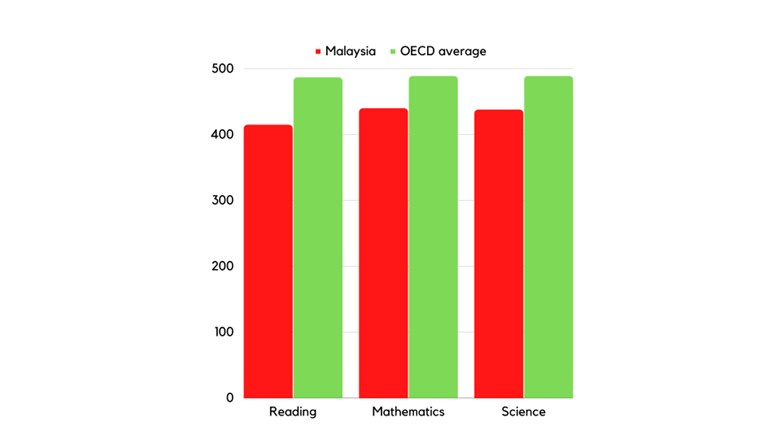

As illustrated above, Malaysia consistently scores well below the OECD average in reading, mathematics, and science, scoring 415, 440, and 438, respectively. The OECD averages for the same are 487, 489, and 489 (“Malaysia Student Performance PISA 2018”, OECD Education, 2018). The most jarring result is Malaysia’s low performance in reading literacy.

Figure 1

Source: EMIR Research

As many as 13% of children in late primary schools are not proficient in reading, and 50% of 15-year-old Malaysians have a reading capability below their level (“Tackling low reading proficiency in school-going children”, The Star Online, June 22, 2022).

In addition, research by Taylor’s University School of Education has shown that children who aren’t able to read according to their respective grade levels (e.g., standard 5 in the Malaysian context) are more likely to drop out of school as low proficiency in reading. As reading is basic/fundamental, such children can’t use their reading skills to excel in other subjects.

Though there are no current statistics on the dropout rate of Malaysian students to reveal the exact severity of this issue, it’s still a critical and serious problem that exists and must be definitively addressed.

The most effective way to promote literacy skills is by reading more. However, few children are provided with a conducive learning environment to develop this interest. The findings from a study by Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) suggested that motivation, interest and prior vocabulary knowledge were the key factors that influenced learners’ reading comprehension skills (“Factors affecting reading comprehension among Malaysian ESL elementary learners”, Kiew S., Creative Education, Vol. 11, 2020).

This is where grassroots initiatives such as MYReaders, come into play to empower teachers and parents to promote reading literacy.

MYReaders has its origins in the concern of four English teachers realising that some of their students could not read or understand basic English. The situation led them to design a structured reading programme with one-on-one support at its core using materials adapted to personal experience.

MYReaders operates to empower not only teachers but also parents, students (as peer mentors) and external volunteers to play proactive roles in teaching reading literacy.

This stakeholder engagement model encompasses learning at schools (by teachers and students acting as peer mentors) and home (by parents) as a comprehensive coverage to address reading literacy systemically. If an NGO with less than 20 staff members could impact over 34,000 students in 9 years, imagine the impact of a system like this if formally implemented into our education system.

There has been much intense discourse on the outdatedness of the classroom model. It’s time to question if getting a child to sit and passively listen for 6-8 hours a day is an effective way for them to learn and grow or if there are alternative class models to reinvigorate the Malaysian education system.

Based on compiled findings by Helen F. Neville from PBS (Public Broadcasting Service), the average attention span works out to be like this:

- 2 years old: four to six minutes

- 4 years old: eight to 12 minutes

- 6 years old: 12 to 18 minutes

- 8 years old: 16 to 24 minutes

- 10 years old: 20 to 30 minutes

- 12 years old: 24 to 36 minutes

- 14 years old: 28 to 42 minutes

- 16 years old: 32 to 48 minutes

Yet, classes indiscriminately last for at least 1 hour in the Malaysia context.

In addition to the ineffectiveness of current classroom teaching, several personal and socioeconomic factors may affect a child’s emotional state which in turn influence their academic performance (“Socioeconomic Status as a Mediator in Developing Emotion Regulation Among Students in Secondary Level Education”, Iqbal S., International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, Vol. 15, Issue 8, 2021).

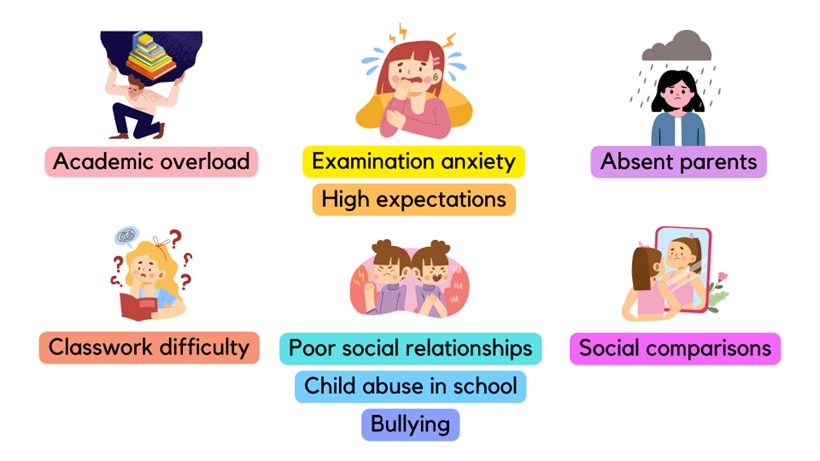

For example, a qualitative study of primary school students in Kuala Lumpur found that 10 main factors led to academic stress (“Factors Of Academic Stress Among Students In A Primary School In Kepong, Kuala Lumpur: A Qualitative Study”, Aiman N.H.I., International Journal of Education, Psychology, and Counselling, Vol. 5, Issue 34, 2020).

Figure 2

Source: EMIR Research

These factors were academic overload, classwork difficulties, examination anxieties, high expectations (both self-imposed and by parents and teachers), poor social relationships, bullying at schools (verbal and physical abuse from teachers and staff), absentee parents, domestic violence (between parents and also between parents and their children) and social comparisons.

However, a school can still ensure that a child’s experience in school contributes towards their individual development holistically.

Though virtually impossible to completely banish, the mentioned factors can be reduced. A potential model is for schools to adopt a more self-directed approach to learning – with teachers taking up a more facilitative and guiding role – where classes aim to empower and inspire students to ask questions and find answers themselves.

Learning need not be passive.

First-hand trial and error and techniques such as “self-explanation”, “elaborative interrogation”, and “retrieval practice” are research-backed learning practices proven to be highly effective (“6 Effective learning techniques that are backed by research”, Lifehack, September 28, 2022).

Through this self-led and collaborative approach to learning, schoolwork also becomes an avenue for students to develop their social skills, relationships, and interpersonal skills. This model would also work in the teacher’s favour to reduce the redundancy and chaotic nature of their current job scope, allowing them to focus on ensuring no student gets left behind in their learning.

A practical example of these principles at play would be in extracurricular activities (ECAs) and university-style coursework, where students seek out and disseminate information themselves – learning skills such as teamwork, public speaking, basic technology savviness and design as they carry out their projects along the way.

This introduces a breadth of exposure to student learning whilst also strengthens the depth of their practical and social application. Exemplary global models include the Finnish education system and the International Baccalaureate (IB) from Switzerland, with both countries in 3rd and 6th place for their education system ranking.

In conclusion, EMIR Research recommends the following policies:

- Paid (i.e., salaried) teaching practicums;

- Competitive salary raises for teaching staff with postgraduate qualifications;

- Workload segregation and delineation – dedicated support staff for non-teaching and administrative tasks;

- Expanding and integrating the MYReaders programme into schools for the rural and remote areas; and

- Strengthening the quality of the Pentaksiran Berasaskan Sekolah (PBS) eco-system with a greater focus on projects-based learning (PBLs) combined with and complemented by facilitative teaching (such as flipped classroom) to reduce (albeit not eliminate) back-to-back 1-hour classes. Towards that end, the ratio between PBLs and facilitative teaching and traditional/conventional classroom teaching methodology should be between 50:50 or alternate arrangements as some practical examples.

Jason Loh and Jennifer Ley Ho Ying are part of the research team at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.