Published by The Star, Malaysiakini, Astro Awani, Astro Awani, The Edge Markets & Focus Malaysia, image from Malaysiakini.

The idea of a “Trump Effect” first appeared in research by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). In their nationwide survey of some 10,000 teachers, the SPLC revealed an avalanche of ethnic and religion–linked intolerance among school children, as reported by teachers, that followed immediately after Trump’s election campaign back in 2016. Those were only the early signs of widening crack in American society.

Four years down into Trump’s administration the data shows alarming evidence of a growing “Trump Effect” rippling through the nation and across the globe. Although racism has been an insidious part of American society since its foundation, it has found powerful new expression during the Trump era.

Credible scientific studies indicate that the Trump effect is very real. Researchers find that immediately after Trump’s first political campaign hate crime rate in US jumped to levels not seen since 9/11. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, hate crime statistics – racially or religiously charged hate crime – has been on a steep rise during Trump’s presidency.

The societal fabric in America has been strained to a breaking point during the last four years to the extent that, as reported by a recent Pew Research Center study, about 80% of Trump and Biden supporters indicate they have few or no friends who support the opposing candidate.

This effect will likely linger long after Trump is gone. A profound damage has been inflicted upon a United States divided along ethnic and religious lines.

Trumpism is a harbinger of how identity-politics can destroy society. The delicate interplay of inter-ethnic relationships, unity and empathy that binds every nation makes it resilient to internal and external challenges. An erosion of common national identity should be of paramount interest to all who are genuinely interested in nation-building and safeguarding.

Unfortunately, Malaysians immersed in identity-based politics are all too aware that this phenomenon is real.

At Emir Research, gauging inter-ethnic harmony among Malaysian population is one of our consistent research objectives. In the latest Emir Research quarterly poll, respondents were asked to indicate their agreement to the use of ethnicity and religion in gaining political support. Close to half – 46% of the national representative sample – agreed to invoking identity politics in contrast to only 9% who categorically rejected it. The remaining 44% were still unsure.

Attempts to understand the demographic background of those who support identity-politics in Malaysia revealed there are more identity-politically charged respondents among rural dwellers, lower income earners and lower qualification attainers. Interestingly, ethnic dimensions did not show significant difference in distribution of responses. In other words, the respondents from any ethnic group were equally likely to indicate their agreement to the use of identity-politics. This is because there were more powerful factors at play which we were yet to discover.

Triangulating these quantitative findings with earlier Emir Research qualitative findings, where participants across all Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) unanimously linked sources of ethnic and religious tension in Malaysia to political and social media outlets, prompted us to test this assumption using our latest nation-wide quarterly poll data.

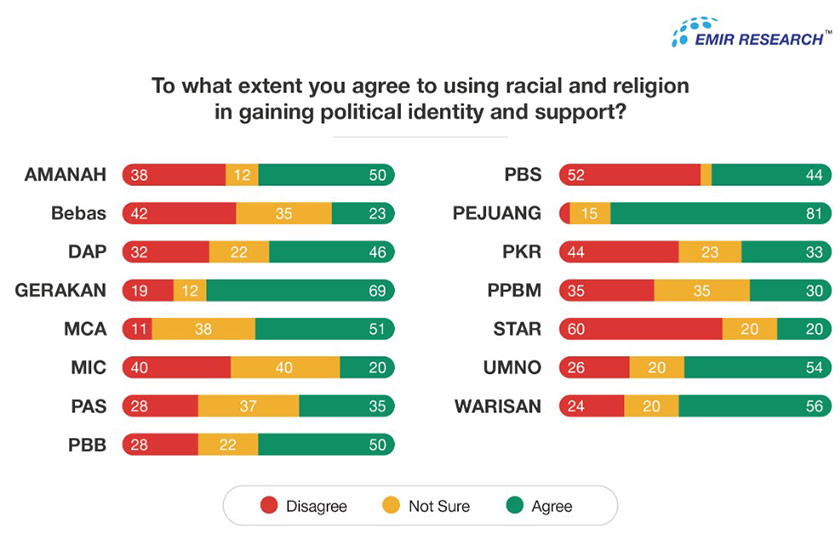

The respondents of Emir Research quarterly poll Q3 2020 were stratified according to the political leader and political party of their choice to gauge how strongly identity-politics sentiment is prevalent.

The following two graphics tell the story. There appears to be a reliable association between identity-politics sentiment and political party of choice as well as political leader of choice by the respondents.

Also note a significant difference in identity-politics support among those who tick “other” as their choice of political party – a finding that sheds more light on Emir Research’s Inaugural Poll discovery of the rise of a “third force” movement back at the end of 2019. This third force appears to be predominantly averse to identity-politics.

The above graphics encapsulate what many Malaysians probably already know. Only now the data proves that the phenomenon is real. And it brings us to this question: are the respondents simply a reflection of the political party/leaders whom they support?

Or it is the other way around, as one of our qualitative research participants philosophically and metaphorically put it: “politicians are only the mirror of the society”.

In other words, we want a government which reflects only our traits, thus allowing political powers to manipulate and divide us.

The important question is whether we want this alarming dynamic to continue, so that we find ourselves at the same divisionary crossroads that the Trump effect has brought the US to.

Malaysians cannot afford to have a divided, unstable and weak Malaysia while facing the unprecedented challenges of the moment. The danger of overindulgence in identity politics is not only in building up ethnic or religious tension, but also in empowering political leaders to cater only to groups that benefit them politically.

Society as a whole is the loser in this bargain. It’s up to each Malaysian to guard against the Trump effect and ensure it does not happen in our time, on our watch, in our Nation.

Dr. Margarita Peredaryenko is Chief Research Officer at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.