Published in MYsinchew, AstroAwani & BusinessToday, image by AstroAwani.

One unanswerable fundamental question which DNB never addressed credibly, based on data manifesting global mobile experience, science, and economics, is why no nation in the whole world is following Single Wholesale Network (SWN) model, also known as Wholesale Open Access Network (WOAN), implemented nationwide, for their 5G rollout if it is so beneficial?

According to “5G Market Snapshot” by Global mobile Suppliers Association, as of February 2023, 156 countries and territories invest in 5G (including trials, acquisition of licences, planning, network deployment and launches). And Malaysia is literally (still) going solo in its nationwide SWN approach for 5G, except for Brunei (with a population of less than 500,000 where infrastructure-based competition is indeed impractical).

There must be a global wisdom out there that we could have borrowed like the rest of our more proactive global and regional counterparts.

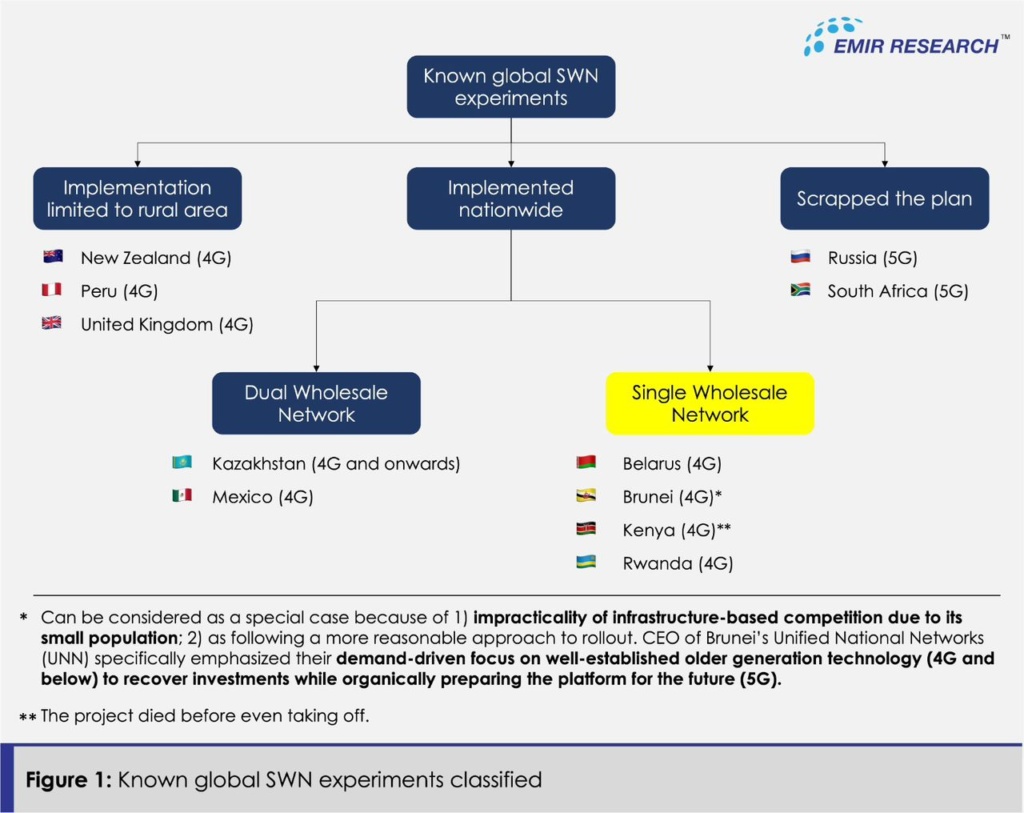

But speaking of known-to-the-world SWN experiments, it is essential to delineate the terms to avoid mixing apples and oranges like DNB routinely does in their commissioned reports and advertorials.

SWN model in focus is Multi Operator Core Network (MOCN), where MNOs share all the infrastructure except their core networks — the exact model deployed by DNB.

The infrastructure-based competition, which is crucial in driving innovation and, therefore, network service quality and affordability, does not exist in MOCN!

Under the MOCN, MNOs can compete only based on service-provisioning characteristics (such as price plans, usage quota etc.) — the main reason other nations intelligently shy away from the MOCN.

However, it is also important to note that a single wholesale-only network limited to fibre, like those launched in Bahrain or New Zealand, for instance, is something rather beneficial for a nation and can play a key role in closing the urban-rural digital divide. Unfortunately, however, DNB does not do this and ignores the problem of our national fibre backhaul completely while focusing only on the last mile service delivery (refer to “Malaysian 5G Rollout: Digital Divide Whitewash” for details).

Also, SWN models limited to rural areas are a promising avenue in the presence of adequate nationwide dark fibre coverage. However, again, DNB is not doing this either.

Instead of having a nationwide SWN, some countries opted for a Dual Wholesale Network (DWN), which only very marginally solves the lack of infrastructure-based competition. However, the presence of DWN is also why Kazakhstan or Mexico did not do as bad in terms of the resulting quality and affordability of mobile internet services compared to their counterparts who pursued SWN.

The above important distinctions, graphically summarised in Figure 1, deem the comparison more meaningful with Belarus, Brunei, Kenya, and Rwanda.

Even among the countries that dared the nationwide SWN model, there was never a notion of a “supply-driven” approach on top of the already problematic SWN model.

For example, the CEO of Brunei’s Unified National Networks (UNN)— the case so often cited by DNB out of context—specifically emphasised their demand-driven focus on well-established older generation technology (4G and below) to recover investments while organically preparing the platform for the future (5G)! Furthermore, Brunei, with less than 500,000 population, stands in its own space as a unique case.

Belarus, until now, remains at the lowest of the global mobile network coverage, quality and affordability charts (refer to “Single Wholesale Network: Global Experience” for details).

In Kenya, the negotiations were too complicated and prolonged, holding major stakeholders back, which sounds familiar. It was not until Safaricom, Kenya’s largest telecommunications provider, pulled out of the deal, resulting in the project dying before it took off.

Rwanda, however, is an interesting compare-and-contrast case study.

Before its joint 4G/LTE SWN experiment with Korean Telecom (KT), in 2007 Rwandan government initiated a project with the same company (KT) to build a national backbone network to connect the Rwandan capital with other major cities. Hence, the Rwandan government ended up having an extensive backhaul capacity to various populated areas — a critical asset the Malaysian government does not have to date and still gives little importance to it. This is why DNB is “leasing fibre” (most likely bandwidth through fibre) from Telekom Malaysia.

In 2013, the Rwandan government established a joint venture with KT again (49% share by the Rwandan government and 51% by KT), selected without open tender, eventually becoming known as KT Rwanda Networks (KtRN).

Noteworthy, unlike the Malaysian, the Rwandan government did not put at risk people’s money (DNB’s government-backed sukuk) but contributed in the form of national assets (valued at US$130 million) — fibre optic, national data centre, spectrum and 25-year exclusive license for KT to make the spectrum available under a non-discriminatory wholesale basis to Mobile Network Operators (MNOs), which covered not only LTE technologies but all future technologies. KT contributed by constructing a 4G LTE network and other investments (US$140 million).

The key expectations from this venture were speed of rollout, increased competition, and reduced prices to end customers. Interestingly, the main narrative was similar — the Rwandan MNOs would not be willing to roll out 4G fast enough to “sweat out” their investments in the previous generation of technology. This looks like a “copy-paste” work by those involved in DNB creation. Only even chatgpt could probably do a better job due to its ability to interpret things in the bigger context and global trends.

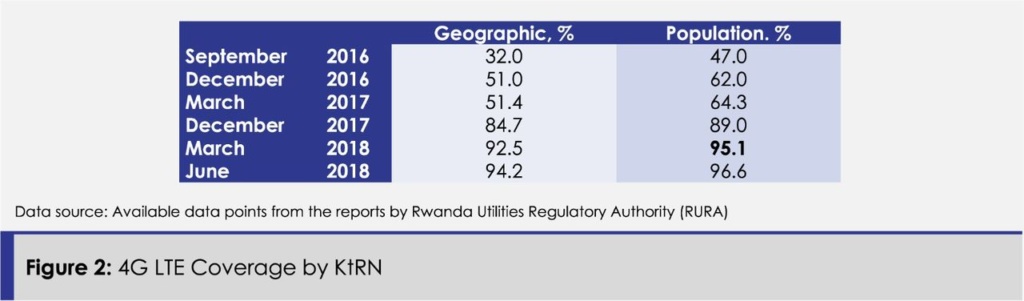

The venture achieved the target output (95% population coverage by end-2017) despite a slight delay (Figure 2).

However, the outcomes were opposite to expectations:

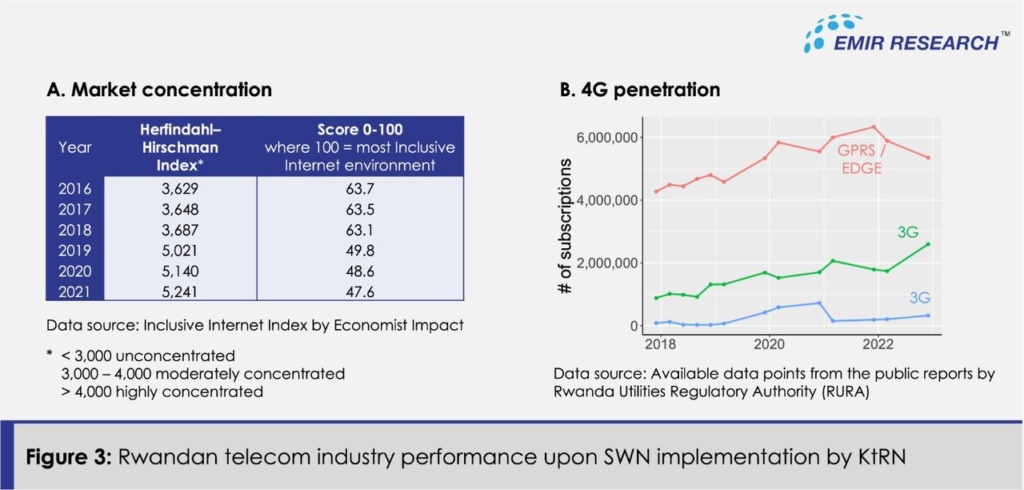

- This network had no positive competitive impact as there were, reportedly, no new Mobile Virtual Network Operators (MVNO) entries. In fact, according to Inclusive Internet Index tracking, Rwandan wireless market concentration even increased (reduced competition) over recent years (Figure 3A).

- 4G adoption has been extremely low to date (Figure 3B) attributed to few reasons: 1) high 4G prices caused by wholesale arrangements, 2) lack of affordable smartphones, 3) lack of knowledge by the broader population of how to utilise technology (refer to “Roadmaps for 5G Spectrum: Sub-Saharan Africa”).

KT accumulated significant losses over the years – close to $US100 million Between 2014 and 2018, according to figures from the United States Securities and Exchanges Commission.

But, at least, in Rwanda’s case, these losses were not backed by rakyat’s money (through sukuk) or forcefully pushed in an “innovative” “supply-driven” fashion to national MNOs. After all, national MNOs contribute immensely to the home economy in multiple ways—very directly through Universal Service Provision fund, taxes, and dividends to Government-Linked Investment Companies, which in total with an indirect contribution through the industry effect far outweigh laughable DNB’s cash flow projections (refer to “Malaysian 5G Rollout: Spectrum Economics & Deadweight Loss”).

Expectedly, Rwandan MNOs were blamed for charging high prices for their 4G offerings. However, MNOs responded that they earn almost nothing from some packages, largely reflecting the wholesale price they had to pay KtRN. The situation did not improve significantly even after KtRN reduced the wholesale price by 30% in 2016.

As EMIR Research already discussed DNB’s inability to provide lower cost due to many hidden costs either not stated outright or not considered (refer to “Malaysian 5G Rollout: Camouflaged Costing Acrobatics”), we shall not expect the eventual 5G pricing situation to be different from Rwanda’s experience. Moreso, we shall not expect this for yet another reason.

DNB’s price of RM0.13 per gigabyte (GB) in its latest advertorials (reduced from the initially quoted RM0.20 per GB, obviously for even better advertorial optics) says nothing about the eventual price to consumers.

The official 5G cost model published by the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) in the Reference Access Offer (RAO) uses bandwidth-based pricing — RM30,000 per gigabit per second (Gbps) per month to access the 5G network. With this information, we can arrive at about RM 0.09 per GB cost to an MNO given the full utilisation of the network (for calculations, refer to “Are we on the right track for 5G”). However, with 50% network utilisation, this cost will double. With 10% utilisation, it would already be about RM0.93 per GB.

Moreover, this wholesale price includes only Radio Access Network and excludes other network elements and services where MNOs incur costs. Do remember that unlike even in Rwanda’s experience, DNB is focusing only on the last mile.

Hence, what MNOs can charge to end-consumers, even if to at least cover their costs, depends primarily on network utilisation.

The above brings us back to reflection on how KT has accumulated losses in Rwanda as demand has not kept up with supply. Do pay attention that all those factors stated as the main contributors to low 4G penetration in Rwanda are totally translatable to expected scenario for 5G in Malaysia for N number of years down the road, greatly contingent upon how quickly the current administration can turn around all other “anti-trend” legacy policies related to 4IR, including the education system ignored for decades.

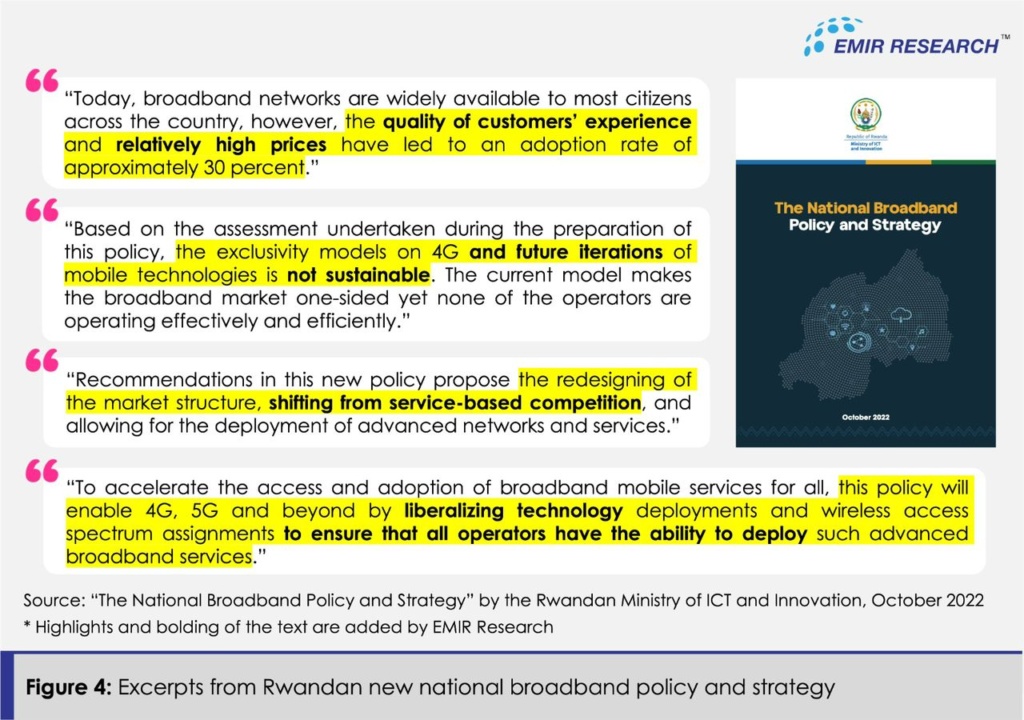

At least, Rwanda seems to be done with its SWN experiment and finally takes a swift intelligent U-turn in the right direction by reinstating spectrum technology neutrality to return infrastructure-based competition and therefore innovation edge to their telecom industry.

The focus should be not on coverage but on innovation!

“The National Broadband Policy and Strategy” by the Rwandan Ministry of ICT and Innovation, adopted in October 2022, encapsulates their experience with SWN well (refer to the pearls of wisdom in Figure 4). Malaysian policymakers must study this policy document.

Apparently, Rwanda has learned a painful lesson about how innovation and, therefore, network service quality and affordability, does not live in SWN model which arrests the infrastructure-based competition. And even the Dynamic Radio Resource Partitioning (DRP) used by DNB (for which DNB-Ericsson reportedly received an award) would not solve this fundamental problem!

Let’s not forget at one time, the Rwandan SWN experiment also won an innovation award.

Given the number of “negative innovations” that we observe in DNB’s rollout model on top of the already problematic SWN approach, we probably should be given a Nobel Prize straight, but only in some kind of upside-down reality like in mystical series on Netflix, “The Stranger Things”.

How long should developing countries suffer from being the lab for “innovation” experiments by colonialists (national and supranational)? We should politely urge them to apply their “innovations” in their lands, while in our lands, we must do what is right for our people, always driven by data, science, and economics!

Dr Rais Hussin is the president and chief executive officer of EMIR Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.