Published by AstroAwani and MySinchew, the featured image is AI-generated.

As Malaysia aims to become a technologically advanced economy and attract high-value foreign direct investments (FDIs) and talent both regionally and globally, it is crucial to expediate the transition from the Single Wholesale Network (SWN). This decisive action will propel the country’s development and reinforce its position as a prime destination.

Although infrastructure sharing has become a significant trend in the global telecom landscape, sound policymaking now emphasises specific restrictions on infrastructure sharing to protect competition and ensure at the very least two networks (Houpis et al., 2016; Yamajo, 2022), as opposed to the extreme case of SWN.

Meanwhile SWNs, as “mid-late 2010s solution”, are evidently dying as a trend (“Policy Trends in The Aftermath of Single Wholesale Networks” by GSMA, January, 2024).

We could have earlier benefited from the experience of countries that wisely avoided SWN—comprising a significant majority—or those that initially struggled with its implementation but eventually pivoted away, like Rwanda.

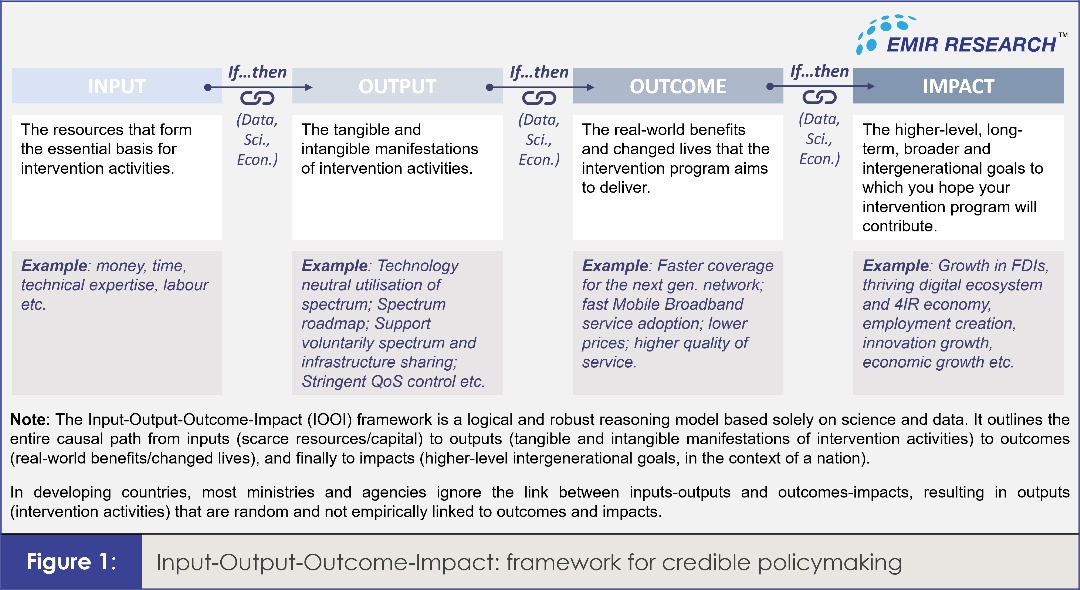

In “Malaysian 5G Rollout—Topsy Turvy Innovation,” EMIR Research (ER) analysed why Rwanda’s 4G SWN is an intriguing case study, offering a more accurate “apples-to-apples” comparison among all known SWN experiments. This case also exemplifies well the need for national policies to adopt the Input-Output-Outcome-Impact (IOOI) approach that ER consistently advocates. Policymakers must demonstrate, using science and data, the expected outcomes and impacts based on committed inputs and outputs. A robust empirical link must exist between inputs-outputs (resources/efforts committed) and outcomes-impacts for the nation (Figure 1).

While Rwanda’s 4G SWN experiment offers a fairer comparison, it’s essential to recognise that delinking network ownership from service delivery—an inherent issue in SWNs—will have an even more pronounced negative impact for 5G than for 4G. This is because 5G requires much closer coordination between the network and end service users.

Rwanda’s SWN deal, signed in 2013, involved the government providing an extensive dark fibre network, a national data centre, and a spectrum as inputs. As outputs, the government granted Korean Telecom (KT) 25-year spectrum exclusivity for 4G, which established the national 4G SWN, eventually known as KT Rwanda Networks (KtRN).

The expected outcomes were rapid coverage expansion, swift mobile broadband (MBB) adoption, lower prices, and improved service quality. Earlier, the ER’s analysis showed that none of these expectations materialised. However, had these outcomes been achieved, Rwanda would have seen long-term impacts like increased FDIs, greater digitalisation of its economy, job creation, and overall economic growth, as suggested by data, science and economic principles.

The reality diverged significantly from expectations, a trend consistently observed in other nations experimenting with SWNs (GSMA, 2019; GSMA, 2021; ER, 2023; GSMA, 2024). Coverage targets faced slight delays, 4G adoption stagnated mainly due to high prices, and there was a lack of competition in quality of service (QoS) as individual MNOs lost control over the network. Additionally, there were reportedly no new entries of Mobile Virtual Network Operators (MVNOs), contrary to initial expectations.

KTrN struggled to deliver high 4G penetration, with only 3.87% adoption even as of June 2023 (RURA)—just before Rwandan MNOs could finally launch their own networks in July 2023.

By the end of 2021, just 24% of Rwanda’s population used mobile internet, despite 75% living in covered areas, indicating a 14% higher usage gap than the regional average (GSMA analytics). This disparity is particularly concerning, given the surge in mobile internet adoption elsewhere during the pandemic, which helped reduce isolation and manage the crisis. One can only sympathize with Rwandans when considering the potential social welfare losses that extend beyond the dry statistics.

Even by the end of 2022, the adoption rate had only reached about 30% (Ministry of ICT and Innovation, October 2022). This was just before Rwanda implemented drastic policy changes to revitalise its telecom industry.

Notably, in Rwanda’s case, a foreign company (not government-owned or government-linked) has incurred substantial losses, thereby limiting direct exposure for Rwandan taxpayers. However, the immense opportunity costs from the government’s unproductive commitment of critical resources adding to considerable deadweight loss (see “Malaysian 5G Rollout: Spectrum Economics & Deadweight Loss”) will sadly go largely unaccounted for.

Relatedly, Rwanda’s FDIs have been dwindling since late 2014. Although this trend isn’t exclusively linked to the Rwandan 4G SWN saga, it coincides with its inception. After all, investors, being tech-savvy and well-informed, are keenly aware of the anticipated outcomes and impacts from such developments, based on data, science and economics.

Similarly, in line with expectations, Rwanda’s score in the Global Innovation Index (GII) has steadily declined since 2016, a year marked by significant advancements in the 4IR, with mobile connectivity as a critical driver.

Fortunately for Rwandans, policymakers acted decisively. On October 18, 2022, they ended the 4G monopoly by reinstating spectrum neutrality, alongside other policies like Connect Rwanda 2.0 aimed at bolstering mobile internet adoption. By end-July 2023, Rwandan MNOs had launched their own 4G LTE networks, offering high-speed internet at existing 3G prices—a clear liberation for 4G adoption, best illustrated by Figure 2.

According to the “Digital in Rwanda” reports, as of February 2022, the share of broadband cellular mobile connections was 53.5%, increasing only to 59.8% by January 2023. However, by January 2024, the share jumped to a remarkable 86.6%, indicating a sudden, substantial, and rapid rise in mobile broadband usage.

Coincidence or not, FDI inflows into Rwanda (Figure 3) surged by 63.5% in the first half of 2024. Contrary to the fearmongering claims of staunch Malaysian SWN defenders, FDIs, including those from Korea, accelerated into Rwanda, acknowledging essential policy changes such as reversing its SWN. These changes are part of the broader business- and innovation-friendly reforms based on data, science, and economics, which the Rwandan government is currently championing while, importantly, also making significant strides in fighting corruption, to which the IOOI approach is the best antidote.

Rwanda is expertly capitalising on global economic uncertainty, especially regarding the USD and other toxic Western assets, by implementing policy changes that boost investor confidence in the country. This mirrors the ER’s recommendations to Malaysia in “Ringgit’s Resurgence: Beyond the Dollar’s Decline.”

Time will tell whether Rwanda’s key policy shifts will yield broader impacts. However, noticeable improvements are already evidenced in its GII 2023 and 2024 scores.

Interestingly, recent GII reports show Rwanda’s GitHub commits have simply soared to an outlier level (Figure 4).

Although not a traditional economic indicator, GitHub activity can be a useful proxy for gauging a country’s Industry 4.0, digital economy and innovation.

This metric can indirectly indicate economic activity, especially in the tech sector. It reflects a thriving software development community, signalling innovation and new product development in industries reliant on software, automation, or digital services (FinTech, AI etc.).

Frequent GitHub activity also hints at the skill and productivity of the tech workforce.

Therefore, Rwanda seems to be on track.

However, perplexingly, as one nationwide SWN fails, another is being established, now in Ghana.

Apparently, despite mounting evidence against this model’s viability, any nation not adopting the IOOI approach risks ending up with “its own SWN,” whether literally or metaphorically (i.e., policies that make no sense).

From its painful experience, Rwanda learned that:

- A monopoly-like structure unavoidably restricts competition and reduces incentives to improve service quality or lower costs to consumers.

- SWN reduces MNOs’ ability to differentiate their services or drive innovation.

- Without competitive pricing and investment incentives, that are impossible under SWN, the benefits of a technology rollout might not fully reach the population.

As a result, Rwanda wisely made a quick U-turn to a more agile, flexible and collaborative rollout model that has been proven empirically to promote competition, private sector investment (including in underserved areas), and encourage growth in the quality and availability of mobile networks!

Therefore, Malaysia should immediately reinstate technology spectrum neutrality and implement other critical measures ER recommends in “Gegenpressing Stalled Pathway: The Urgency Of Malaysia’s 5G Transition.”

As a progressive country, Malaysia, too, cannot rely on solutions from the mid-late 2010s, which have already proven ineffective. We must accelerate our efforts to align with modern global techno-social trends, particularly at this opportune moment when global investors need to see us as credible policymakers.

Dr Rais Hussin is the Founder of EMIR Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.